All pictures courtesy Eddie Otchere

Eddie Otchere is a curator, photographer and educator. His photographs have shaped the visual history of music for the last three decades, with iconic portraits of Aaliyah, Biggie Smalls and Wu-Tang Clan, to name just a few. In March, a series of Eddie’s photographs will be printed in Who Say Reload, an oral and visual history chronicling 36 classic drum & bass and jungle tracks of the 90s.

Enthused by film photography during his teen years, Otchere used community darkrooms in South London to hone his printing skills. As a young hip hop obsessive during the genre’s golden age, he felt compelled to document the culture. His first cheque would come from a shoot with Jeru the Damaja, kicking off a career that would influence the iconography of music on both sides of the Atlantic.

Many of Jungle’s original architects were b-boys who had become attracted to the rave scene. Otchere was no different, as raves moved from the fields to urban spaces he began to shoot events at the Lazerdrome in Peckham. “I documented the rave scene, as well as hip hop, cause in many respects they fell together. It was a beautiful coming together of both cultures. The demographic started to change and it became Black kids and white kids dancing under one roof, which made London a better place.”

During this period, breaking away from the pitched-up vocals and piano riffs of the increasingly commercial happy hardcore, a darker sound, pioneered by Fabio and Grooverider, emerged in Britain’s inner cities. Later evolving into jungle, the sound reflected a sombre time of economic downturn where many club spaces began to close and events were hit with racially motivated over-policing. Forced to go underground, the South London photographer recalls putting sound systems in squats to put on jungle nights, “the police would come to a rave with their sirens on. Then suddenly you’ve got tunes with sirens in them because it was like, ‘remember that night when we heard the sirens?’ Let’s just throw ‘em in there and put a bassline underneath it along with some foghorns.” Jungle was met with negative and racist reactions from the media who framed the scene as violent and aggressive. Part of Otchere’s motivation to document the subculture came from a will to counter these dehumanising perceptions. “At some point dancing becomes really dangerous to the conservative narrative. Our culture was being criminalised in front of our eyes and I wanted people to see how beautiful we were.”

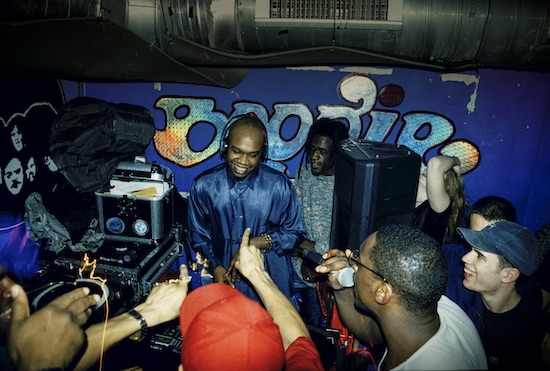

From 1994 to ‘96, Eddie was asked to be the official photographer for Metalheadz. Looking at his archive, Eddie says, “The photographs essentially document the Metalheadz experience as it occurred at the Blue Note”. Using a 35mm Canon EOS10, Eddie saw himself as a 20th century flâneur, a modern spectator allowing the spontaneity of the city to inform his camera. He would be out shooting London’s urban landscapes before bringing this candid mentality to Hoxton Square on a Sunday evening. “It was like street photography meets a sound. It wasn’t a job at the time. I was just trying to capture what the sound was doing to our generation. I was documenting street culture. I shot on film, it’s not manipulated. What you see is what you get. ” Although photographs are mute by nature, Geoff Dyer once said that great photographs are to be listened to as well as looked at. None more so than the front cover of Who Say Reload. “Grooverider drops a tune. The place fucking explodes. Goldie goes mental and runs towards the decks and I hit the shutter.” Eddie continues, “It represents what the book’s about. The tunes that forced people to hail for the rewind.”

Dubbed by Goldie as the ‘Studio 54 of the 90s’, the Blue Note became a melting pot for sonic expression and breakbeat science, where many future legends of the genre would cut their teeth. “There was a lot of innovation. It was a furious time where it went from jungle to drum & bass as we know it because of this pressure cooker that exploded.” As the sound morphed – a process Otchere describes as “twisting up” – the club became a focal point for darker, more futuristic beats played through the highly esteemed Eskimo Noise sound system. “You’d be in a room full of producers, there’d be a geezer upstairs cooking Jamaican food and you could just bun-it-down in there. It was a real creative space. I’ve danced in Tresor and many clubs across Europe but they don’t have the same buzz.” The intimate Sunday sessions at the Blue Note have since gone down as some of the most influential in British bass culture, with Kode9, Mala and Ben UFO all speaking with reverence for the revolutionary sound and its lasting impact.

While he was at college, Otchere co-authored a novel entitled Junglist under the alias James T. Kirk. In the introduction, the narrator proclaims that “Jungle is and will always be a multi-cultural thing.” I asked Eddie to consider this statement nearly three decades on. “The scene was open minded and stayed that way for a long time,” he said. “Going to Metalheadz on a Sunday you knew you were gonna eat rice and peas with curry goat. You eat first, you go and have a smoke, and then you dance. It’s part of Black culture to explore life this way.” Otchere continues, “It was important that everyone came with what we may call a Black attitude, essentially an accepting way of thinking. Black culture is a harbour for other cultures to express themselves and it offered a lot of people protection in the face of a conservative white, middle-class culture. Some MCs spoke in Patois, others in Cockney slang. The Black attitude got rid of a problem, which allowed everyone to be just be.”

Reflecting on his portrait of Kemistry & Storm, a trailblazing duo, integral to the rise of drum’n’bass, Otchere stresses the importance of women to the story. “Drum & bass became too male before it became too white. History will never say this, but women ran jungle. Women ran all the labels. Kemistry and Storm ran Metalheadz, Yoko ran Trouble on Vinyl. Women were very much part of the DNA of the music and the culture. Once women left the culture, I was out.” Reflecting Otchere’s sentiment, Julia Toppin’s research has sought to correct the genre’s history by remembering the range of women vocalists, MCs, and DJs who were vital to the scene and its evolution.

Drum’n’bass’s debt to the Windrush generation is well documented, most notably for their use of throbbing basslines, MCs, and dubplates. Otchere’s photo essay on the Channel One Sound System was recently exhibited at the Dub London exhibition. “After jungle, I started tracing sound system culture back to the 1940s. I wanted to understand how sound systems were part of the English story and how they evolved in England. Islanders came over to this island and with the expanded sonic range, bass culture develops. There is a spiritual thing around the sound system. It is the ultimate in analogue technology. They say a lot about what working class people can do.” Otchere goes on to consider the link between this series and his Metalheadz work, “they helped us to develop an ear for deeper frequencies. People like Dillinja are the sons of soundmen from the 70s and 80s.”

As we continue to talk about jungle’s influences, Otchere cites the presence of a Hardcore continuum. “The Second Summer of Love bubbled up into Hardcore, Darkcore, Jungle, Drum & Bass, Garage and so on… I see generations adopting this mentality and creating their own scene off the back of it. The same template, in terms of the culture and cutting the dubs, but switching up the sound for a newer audience. There was a formula that was set which only changed once 2005 came along and dubplate culture was put aside, as tunes were sent digitally and cut onto CDs.”

Mirroring the evolution of sound, it’s hard not to also see a visual continuum, from Otchere’s work to that of subsequent British subculture archivists. The likes of Ewan Spencer, Simon Wheatley and Vicky Grout immediately spring to mind. Documentation of club culture is often relegated to the status of ‘club photography’, undermining the social significance of alternative visual histories. Eddie’s pictures record the beginning of a largely undocumented subculture, style, and sound that would go on to rewrite youth culture and dance music in Britain and beyond.

It has been said that jazz photographer Guy Le Querrec has an eye that listens. In the same fashion, Otchere’s audible series is inseparable from its musical counterpart. When we look at the photograph of Grooverider we can hear that rumbling bassline underneath some raw, energetic percussion. In his own words, he created a “visual poetry crafted in the baptism of sound.”

Who Say Reload will be published by Velocity Press