Thomas Ruff’s talent has the most obviously protean disposition of that group of well-known photographers trained in Düsseldorf by Bernd and Hilla Becher. His is a restless and relentless testing of the boundaries of photography. His practice seems at odds with the arguably more settled approach adopted by his fellow greats (also deeply influenced by the archive-fixated Bechers) such as Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, and Thomas Struth. He is, if you are euphorically inclined, the Todd Rundgren figure of the group, more alert to diversion than the others, keener on experimentation, fonder of capturing other-worldliness, besotted by astronomy, history, hallucinatory visions, the erotic.

Ruff’s work escapes from those hard realities of existence typified in the work of his peers, with their interest in repetition – see Gursky’s lines of supermarket products; space – as evidenced by Höfer’s lonely museum interiors; and absorption, as with Struth and his distracted, non-theatrical posing of museum visitors. This relaxation from the self-imposed restrictions of the Becker model sees Ruff push with the insistence of an excavator at the coalface of abstraction. What we get at the Whitechapel, then, is a lot more than the clichés of meta-photography, the dry cross-examination of the discipline per se. Ruff is a more ambitious artist.

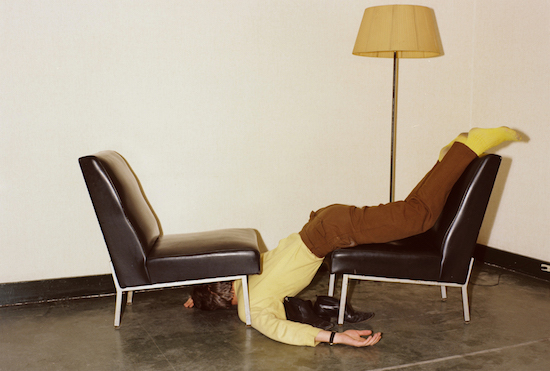

There are examples from, impressively, no less than eighteen series of images – so let’s crack on. The show begins with an atypical feint and features the only self-portraits here. In L’Empereur 06 (1982), we see the inverted artist draped lazily over one chair, his head crazily stashed under another. A lone standard lamp stands guard. These snapshots capture a throwaway ennui akin to Bruce Nauman’s bored pacing in the studio or those disposable one-minute sculptural shenanigans of Erwin Wurm. Jumping forward in time on the adjacent wall there are some examples from Ruff’s m.n.o.p. series (2013). Here he takes some prints obtained at auction – photographs showing the interiors of the New York Museum of Non-Objective Art set up by Solomon R. Guggenheim in 1939 – and then digitalizes them adding coloured tinting to the walls and carpeting with an alluringly faded aura. Oddly these are strongly reminiscent of the great Hipgnosis cover for 10cc’s Sheet Music (1974), with a similarly suggestive tone of tinting done by Maurice Tate.

In a more recently analogous series, one of which is w.g.l. 07 (2017), we get images of the Whitechapel itself from 1958, featuring some monochrome Jackson Pollock paintings. Ruff’s alterations – a sombre pink ceiling with dry sky-blue carpeting – capture a time typified by an optimism for the future, hinting at the new frontier ahead. We imagine hearing some late bebop Savoy sides as a soundtrack to this belated British birth of cool.

The inescapable and gigantic Portraits secured Ruff’s reputation. You cannot help but recognize these instantly in the main downstairs space as you arrive. They remain powerful transformations of the quotidian into the iconic. These huge pictures of blankly staring, unsmiling, serious young Germans nod to August Sander’s groundbreaking People of the 20th century project. Here’s the Porträt P Stadtbäumer (1988), with her gleaming forehead and scary blue eyes. She wears (uh oh) a brown shirt and might be seen as a darkly ironic vision of Aryan health. She cannot help but remind you of the awful Baldur von Schirach and his sinister League of German Girls.

It’s not all bad news – further nods to German history come with some of Ruff’s House series, images of buildings that recall the glory of the Bauhaus, the obsessionality too of the Becher pairing and their wondrous project as with Haus Nr. 11 III (1990).

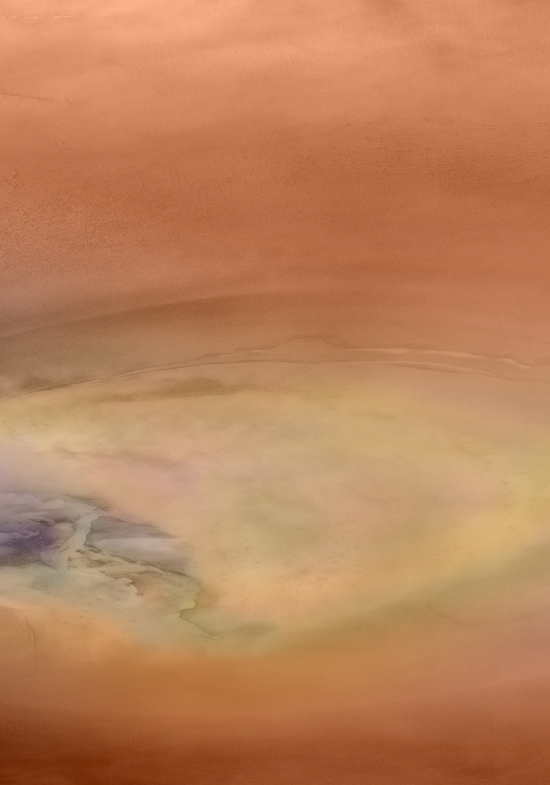

A sense of true proportion comes with the Stars. These images of the night sky, space itself, such as 16h 30m/ -50° (1989) quickly serve to remind us of our miniscule position in the cosmos, were we inclined to any delusion of omnipotence by the monumental Portraits nearby. That sense of the mighty, unknowable enormities hidden out there somewhere, is only reinforced by Ruff’s pictures of the planet Mars such as ma.r.s.01_III (2011) – an image that, although we know is real, might be a John Hoyland abstraction for all we knew beforehand.

We are quickly brought down to earth again with a line of small C-prints from the Interiors series – banalities like Interieur 1A (1979), a bathroom sink with a bar of soap that recalls Thomas Demand’s constructions – albeit, you remind yourself, that Ruff’s sources are solid, actual. Again, there is the deliberate clash of scale across the room when we confront jpeg ny01 (2004) – an enormous image of the Empire State Building with smoke billowing catastrophically from one of the Twin Towers. Any sense of reassurance gleaned by the everyday of the Interiors is promptly shattered seeing this blunt reminder of the horror.

ma.r.s. 01_III2011C-print255 × 185 cm© Thomas Ruff

Ruff’s keen interest in the advances of image technology led him to the Nights series – more C-prints that show night vision shots reminiscent of those first revealed to us by press reports from the Gulf War of 1990–91. A banal picture taken in Düsseldorf of some parked cars – Nacht 9 II (1992) – is invested in dread by the grim green light. Dread too comes with the Other Portraits series (1994–95) – ghostly composites made from a machine that contrives to deliver identikit images of suspects. These have something of the scariness of those old Baader-Meinhof wanted posters from the days of the Federal Republic. Hard too not to be reminded of Gerhard Richter’s monumental monochrome painting cycle about the gang – October 18, 1977 (1988). Richter’s Atlas – his well-known collection of cuttings, is referenced too with some of Ruff’s appropriated Newspaper Photographs (1990-1991). More recently Ruff has worked with photographs from news archives juxtaposing and overlaying information on the reverse of the prints onto the main image such as the soaring jet seen in press++21.11 (2016).

Then there are his naughty nudes (1999-2012), blurred images of pixelated nookie. These could be interpreted as an attempt to steal a frisson of eroticism back from the deadening hand of HD pornography – they reintroduce that adolescent sense of shock – is that really what I think I’m looking at? The Substrates series hints at other hedonistic pleasures. Here Ruff takes manga comics as a source and with digitalized distortion turns these into liquefied dream imagery such as Substrat 31 III (2007), a hallucinatory mirage not dissimilar to the cover for New Order’s Fine Time (1988) done by Peter Saville Associates and Trevor Key.

But with all Ruff’s fascination with the march of modern technology, I left this excellent survey thinking oddly more of the past. His interest in overlapping imagery, transparencies, his Machines series (2003-04) and photograms (2012-15) all suggest a deep affinity with no less a figure than Francis Picabia. An image such as Maschine 3149 (2003) would have made a perfect fit for a cover of Picabia’s magazine 291 (1915–16). From the rigorous objectivity of machine parts to abstraction – Ruff’s photograms are not made, as with Man Ray, from objects placed directly onto photosensitive paper – instead they are created in what he calls a virtual darkroom with a virtual light source. The results, such as phg.07_II (2014) look like a twenty-first century update of Picabia’s Udnie (1913).

Ruff’s escape from habit, his perpetual shiftings, suggest that he might agree with Picabia when the master said – “our heads are round so our thoughts can change direction.”

Thomas Ruff: Photographs 1979 – 2017 is at the Whitechapel Gallery until 21 January 2018