Think of a musical artist. Odds are you’ve conjured up an image in your head rather than a sound or a name. You’ll probably picture them delivering a killer solo, looking pensive in the studio, stage diving or eating valium in the bath. The point is that you’re seeing. I cheated here slightly by using an attributive adjective and concrete noun, but what I hope this shows is that thinking is innately, reliably visual. If I asked you to think of your favourite song or some music, it would, generally speaking, be a challenge. It’s hard to manifest sound alone in one’s thoughts without some manner of visual accompaniment. That’s because the ‘language’ employed by the human brain is primarily one of images. Even if we’re engaging in dense verbal cognition such as preparing a speech, vivid pictures act as the unbidden chaperone of all thought.

Everybody pretty much knows this. And most people that make the music that really obsesses you know this intimately. They know that if you’re going to sit by yourself in bed for several hours getting stoned and staring at the ceiling with their albums blasting that there’s a lot for them to do that goes beyond simply recording lovely songs. Beautiful noise alone isn’t enough to ensure your devotion; they can’t just sell you sound. What they’ve got to do, really, if we speak in grievously reductive terms, is sell you an idea. And, as we know, ideas are images.

One person that understands this as well as anybody is WEIRDCORE. He’s worked on music videos, advertising campaigns and concert visuals for an imposing, multi-genre array of popular musicians and is most frequently cited for his now decade-long collaboration with Richard D. James.

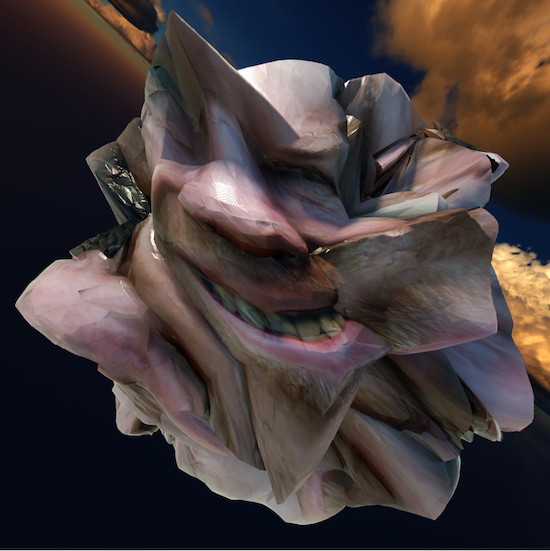

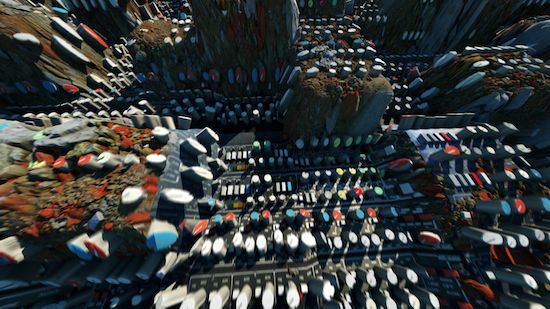

Think of Aphex Twin. You’re thinking about one of those heinous grinning faces, aren’t you? Or that logo stamp that looks a bit like a compass. Or you might be picturing a dizzying slalom through a complexly evolving suburban environment which seems to leap and jerk in real-time according to the whims of some inscrutably powerful deity of urban planning. The latter is one section of Aphex Twin’s latest music video for the track ‘T69 Collapse’, a video WEIRDCORE created.

“I love accidents and mistakes,” he tells me. “Not mistakes, maybe, but things that aren’t planned. One that I was pleased with is the bit in the video where everything’s collapsing, and it looks like an anus. That wasn’t planned, but I noticed it instantly.” Becoming a video artist and designer famed for druggily intense, Harding-test-failing hyperactivity wasn’t something he planned either. “I wanted to do photography and stuff in art school. I was always into drawing, but I used rulers and compasses. I was never particularly good at life drawing and I always had to be aided by technical tools. When I moved to London I had no contacts whatsoever, I just knew Photoshop was my thing. I had like £90 in my pocket. I got work here and there and did the usual thing that you do in London, really. I did jobs to pay the rent and it went from there. I was doing a lot of visuals in clubs and putting on events, and that’s how I made most of my contacts.”

Those contacts now include, alongside Aphex, collaborators as diverse as Radiohead, MTV, Tame Impala, Pharrell Williams, Louis Vuitton, Miley Cyrus and sports giants Nike and Adidas. The work that’s garnered him the most attention is the extreme stuff: all violent strobes, befuddling stabs of colour, hectic free-falls through pulsing chambers of pop-culture reference populated by exploding .gifs seemingly angry that you’re intruding. Before making his name as a purveyor of all things glitchy, he considered culinary school, worked in games design and did graphic intros for the Pokemon series, some of which I recognise from childhood.

“When I was still at college back in 97 I did work at this computer game company up in Whitby while going to school in Scarborough. That was quite a chance thing. My mate was working there. That was my introduction to 3D. I was using 3D Studio Max, 3D Studio Pro or whatever it was called back then. I wasn’t really that interested in computers before the mid 90s. I didn’t have a computer at home and when we did use them at school we had to log in with MS-DOS. But I liked going to the arcades to play Tempest and I enjoyed playing Space Harrier on the Sega. Both games had this directional thing which I think reflects in my current videos — there tends to be forward motion in this game-like environment.”

Now a Londoner, WEIRDCORE began creating live visuals for music soon after finishing school and had stints working on video games, web design and DVD menus. His first high-profile collaboration was with the British musician M.I.A., for whom he created a distinctive set of graphics for her KALA live shows.

“I saw Daft Punk at the Que Club. It was the first time I’d seen a proper visual live show and it was at that point that I was like, ‘Okay, I want to do visuals. I have to do that.’ When I first started working for M.I.A. I thought it would lead onto loads of other jobs, but at the start I was just labelled as the guy that did these crazy graphics that wouldn’t work that well in the mainstream.”

These “crazy graphics”, I learn, involve a lot of time, effort, precision and lingo deployment. Terms like “pixel sorting” and “datamoshing” are bandied about, and I have a hard time keeping up. What results might be a mess, but it’s one that’s been carefully orchestrated. In Aphex Twin, WEIRDCORE found the perfect sonic partner for his controlled chaos.

“I met him in London when I first moved here, at a club in Brixton called Dogstar. I was there with my girlfriend at the time and he was really rude. We emailed him because my girlfriend back then, Ryoko, used to make music. We sent him the demo of her stuff and he was really apologetic about how rude he had been. He had been really drunk. But his main feedback was about the artwork I did for the cover. He responded to the email, said he checked out her demo and was like, ‘Yeah, the artwork is wicked!’ We were like, ‘Oh, this is a bit awkward.’

“2009 was when I first started working for him. The show where we first did face-mapping was pretty lo-fi, really. I just got someone to film the crowd with my crappy DV cam in night vision mode. It was really bad quality. It was for the opening of the Metz Pompidou Centre. I guess we did it as an art piece. We got away with that. Back then I was really into datamoshing [the practice of intentionally corrupting image or video files to create “artefacts”, weird apparitions in digital terrain achieved through compression, distortion, using the wrong gear and so on] because it was fairly new. I would have this corrupted .avi file and I would assign points in the clip to different points on the keyboard and it would datamosh in real-time. With Richard I was using it with a lot of porn and scat… really disgusting stuff. I think I could only really get away with doing that kind of thing because it was Richard, and nobody would really complain to him. You could literally get away with anything.”

Visuals have taken an increasingly important position in AFX’s work, with WEIRDCORE pushing the brand in increasingly hysterical directions (case in point the leering Queen-Richard-cheerleader hybrid monster that presided over the musician’s 2017 Field Day set), perhaps appropriately for an artist who gave his visage an exaggerated, comic priority to mock a genre notorious for its obsession with masks, mystery and enigma. Of course, this sort of telegraphed self-awareness can’t help Aphex escape the thrall of the rave cult, which is autoimmunitary. It doesn’t take a dedicated dance music authority to recognise the antinomy in starting a career of unflagging self-mythologising with a potshot at self-mythology. An ironic mask is still a mask.

“Back in the late 90s he used to just really take the piss. Like, he would turn up at a club and just play his album without even mixing it or anything. Or he’d play noise for the whole set and no-one would complain. And I just wanted to take advantage of that situation where I could literally play whatever I wanted. I’d find this porn and scat and people vomiting and people eating other people’s vomit, these really disgusting clips. They’d work really well with datamoshing because it works with organic movement.” He points out that both he and Aphex have moved on to more hi-fi methods of shocking and appalling, but their interest in grotesquery certainly had its moment in the past. I mention an Arca show I heard about that featured visuals by Jesse Kanda and a long sequence showing someone getting briskly fisted under harsh strobing. WEIRDCORE goes one better.

“One thing Richard requested was this autopsy video from Colombia. I can’t remember what it was called, but I’ll send you the link. It was this Japanese documentary about a guy who lives in one of the roughest places in Colombia who does autopsies and mummification. It’s really disgusting. I’d strobe between different parts of the movie. Richard used to request having that playing in the background before he got me involved in visuals, just playing straight up. Festivals would check it out and be like, ‘Ha ha, maybe not…’” He looks sheepish. “But that was 2009. It’s a lot more sophisticated now.” Does the film show him pulling the brain out through the nose, like they did in Ancient Egypt? “I can’t remember. I’ll send you the link.”

Sophisticated is one way to describe his latest piece of work. The ‘T69 Collapse’ video has amassed nearly a million YouTube views in a week, and features some extraordinarily hectic moments, even by WEIRDCORE standards.

“The reception has been a lot better than I thought, to be honest. I was stuck between a rock and hard place. I was finishing it on a Friday, really into the final stages. And that’s when Richard gave me his first notes, and I’d been working on this for, like, months!” He groans good-naturedly. “I’m like, ‘Okay, I’m finally going to hand this in.’ And then he gives me his notes, wanting it be more sound reactive at the start and to add more flashing bits. Within the same 30 minutes I get an email from Warp going, ‘It failed the Harding test, can you make it strobe less?’

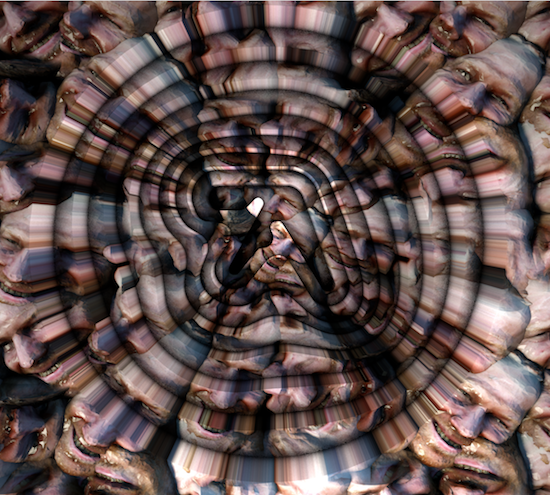

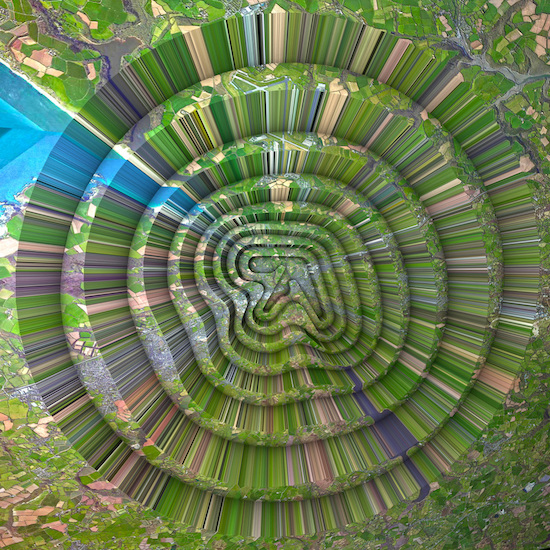

“We were both just keen on making it more intense. To make it pass the Harding test we would have had to reduce the frame rates, add more motion blur and all that which would’ve watered it down. So instead we just ‘collapsed’ the Harding test and made it more intense.” The video was set to debut on Adult Swim, but the segment was cancelled. The Harding test is conducted by software that examines footage for potential triggers for sufferers of photosensitive epilepsy. Aphex Twin’s Collapse EP branding has so far focused on the familiar Aphex logo sinking into a variety of urban surfaces, surrounded by concentric rings. A “collapsed” press release from Warp gave some garbled hints about the album once deciphered by fans, and “collapsed” Harding test images are available to view on the WEIRDCORE site.

“We were really surprised about how quickly the fans figured out what the scrolling text at the beginning says. All of us completely forgot there’s a feature on YouTube to slow it down. I was thinking it’ll just be the nerds that’ll go to the trouble of downloading the clip and slowing it down, but once it was out we remembered that feature.”

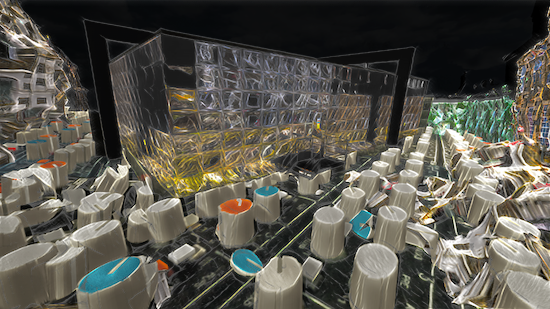

That scrolling text is a conversation between James and WEIRDCORE, and features technical discussion, a debate regarding which real-world locations to include and James’ recent predilections, which include “almond butter and manuka honey”. But the collaborators also spend time together in person. “When I went [to Cornwall] and he was showing me all his gear he was a bit disappointed that I didn’t really know any of it. I think he’s used to showing people that also make music and they’d be completely having an orgasm over his kit, but I had no clue what anything was. It wasn’t particularly exciting for him to show me around. I think he gets kick out of impressing people with all the bits of stuff that he’s got. But if it’s got no meaning for you then it’s not impressive.”

He confirmed that the “silver box” of the discussion is the Faraday Monument in the Elephant & Castle roundabout, where James was erroneously rumoured to live, and that the town scenes are indeed Redruth in Cornwall where the young AFX attended school.

“I asked Richard what places to use in the video. It’s a mixture, but it’s mostly Redruth. He’s from a tiny village nearby. Another one that came up is the Gwenapp Pit. I tried to make an animated version of that.” The pit, also in Cornwall and the site at which John Peel interviewed James in 1999 for the Sound Of The Suburbs TV series, is a church-owned, outdoor amphitheatre used for worship, weddings and performance. It’s the basis of the “collapse” branding, although the real thing has more than seven rings. “The posters were just an evolution of that, really. Once the posters came out, people had loads of different theories, like, ‘Ooh yeah, seven rings, that means seven albums.’ What’s that forum, We Are The Music Makers? There’s loads of full-on Aphex nerds that’ll go to town on there, it’s quite funny.”

So WEIRDCORE is among the masses, reading feedback, enjoying fan debate?

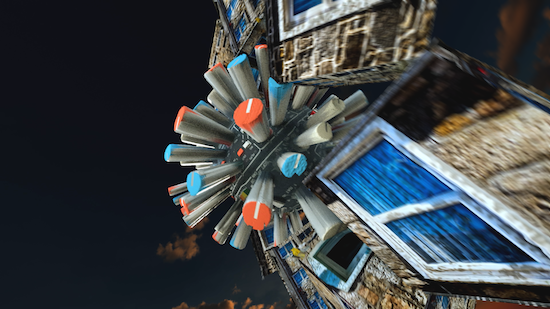

“I read all the comments. I’ve got through the commentary on the YouTube video a few times. It’s all been really good.” Does James also partake? “Yeah, yeah [laughs]. Big time. He reads them for the videos but he also checks them for the shows, because he doesn’t get to see the visuals. The next day he’ll be checking all the stuff on YouTube and saying, ‘Ooh, this could’ve been different.’ But he does. He checks it all. I told him I’d like to use some of his equipment [in the video], collaged within the whole thing, and he was really keen on that. He’s got hundreds and hundreds, if not thousands, of bits of kit, but the one thing he sent me was a picture of his custom-made mixer. I don’t know if many people have those. Of all the things he’s got that’s the one he sent, so it must mean a fair bit to him.”

He adds: "I took the photograph of the mixer and used it in the video. You can see it at several points."

It turns out WEIRDCORE took the trip to Cornwall himself to collect footage for the video’s town sequences. “Someone else lives where he used to live, so I couldn’t really get in and take pictures. But when I was there I just did loads of photogrammetry of all different places and put it all together. It looks like one street, but it’s loads of different locations. Photogrammetry is where you basically take loads of pictures of something from different angles and feed it into this software that recreates it in 3D. It’s loads of 3D models built from photographs. It was me and a friend of Rich from when they were kids and he was leading me around all the different places. I went to Cornwall planning to take loads of pictures of cliffs which I did, but it didn’t turn out quite as good as the building stuff. And I really liked the little cottages, which I didn’t think about at all before I went. They all look the same but there are differences at the same time, and it’s organic but manmade.”

“That part of Redruth and Camborne is one of the poorest parts of the UK. And where I come from in France is a really poor part as well, really post-industrial, and I think Cornwall, like a century or two ago, was one of the richest parts because of all the tin mining. And it’s the same where I come from in France, it was really rich and famous when they started having loads of industry and it’s really rubbish now. It really reminded me of where I come from.”

In the conversation at the video’s opening, James asks him to “edit tight to the beat”, referring to WEIRDCORE’s trademark sound reactivity, where visuals reflect changes in the music.

“I think Richard doesn’t quite understand how complex his music is compared to that made by other people. In the middle section where everything’s collapsing the BPM changes about 150 times. And he was like, ‘Can you not tell?’ [laughs] and I was like, ‘Not really.’ For him its obvious because he made it. That took ages to figure out. What he used is that Cirklon [sequencer]. And that’s really great but it’s not good at outputting files you can actually use. It was really hard to actually figure out what the BPM was at a certain time. He had to send me all the screen grabs from the actual controller thing, and I had to figure out when everything was, and that was a total pain. He did actually give me a maybe 400 page PDF. There’s not really much I could do with it because it’s built for a Cirklon to control other bits of kit but not much else. So I had all this data and couldn’t really do much, so I used it in a graphic way.”

He gracefully evades probing when I broach the subject of unreleased Aphex work and their continuing partnership.

“You’ll have to wait and find out. There’s a few things that I wanted to add in the one that came out but Richard suggested doing different versions. There’s one thing I can say. There will be an overlay of all the data — all the sound analysis, all the BPM changes, all the midi stuff will be clearly visualised. A bit like the kind of user interface overlay they have in Spotify. A little side thing that has all that stuff. It’ll make it interesting for anyone but I think all the Aphex nerds will completely geek out. But there’s going to be other versions of this video. This is V1, there’ll be V1.1 when it comes out and more versions after that. There’s talk of a VR version as well.”

WEIRDCORE also “performs” live alongside James, but you won’t see him — just his coruscating, bad-trip dreamworlds, sometimes on up to 12 screens concurrently. All the visuals at an Aphex show are live, with WEIRDCORE controlling images in real-time. And he has to work at a frantic pace to keep up with music that’s often abrasive and always unpredictable.

“I totally go into the zone. I never know what he’s going to play. He doesn’t tell us beforehand, and if he does it’s often a red herring and he won’t play any of the tracks he claims he will. There have been times where I’ve wanted him to play a tune and then check the recording or the clips on YouTube and be like ‘Oh, he did play that tune! And I was there!’ But I’m so caught up in analysis and reaction that I don’t notice.”

“I think the Aphex tour is maybe different to other ones. Although I did loads of visuals before touring with Richard I’d never really been on tour as such, which is quite different to, say, the lighting guys and the audio engineers and the laser guys. They’d all been touring with loads of other people before but it was my first proper one. I find we’re all quite mature on the tour. Richard will stay in the same hotels as us and we’ll hang out together. it’s really nice. Sometimes the artist will stay in a different hotel. But it’s not a tall like that with Richard. Y’know, we just get stoned and get drunk and whatever. For me it’s a bit like going on holiday. Because I’ve got kids and work quite a lot once I go abroad without the kids it’s the closest thing I get to having a holiday.”

WEIRDCORE is also working with electronic musician Leyland James Kirby, aka The Caretaker, on a long-term six-album project entitled Everywhere At The End Of Time. He’s creating the visuals for the full six album run.

He says: "The reason a lot of my stuff is so high-paced, generally speaking, is because that’s what I tend to get commissioned to do. I never really get asked to do really chilled stuff. I’ve always been keen on doing it but I never get the opportunity, apart from the Radiohead thing that I did. I so wanted to do more of that.

"But then James Kirby asked me to work on a project with him and it was perfect. I had to work with him in a way that didn’t take me that long to complete. I’ve got a kind of template. It took quite a while to do the first [album], but the next ones weren’t too bad as long as I worked within the template.

"It’s all to do with optical flow and time-stretching. Time-stretching is just making things longer. Effectively, I think each album is about 45 minutes. The original clip that I make is maybe three minutes and then I time-stretch it in various ways. The first one I time-stretched it once but the second one I time-stretched it in different parts and in different ways. It’s experimenting with delay, really. The original clip I’m whizzing through this place similar to how I do in the [recent] Aphex video. But if you make that super slow, time-stretched with loads of motion blur it has this quite organic feel.

"I’ve been a really big fan of James Kirby’s work since the late 90s, I used to really love his V/Vm stuff and Caretaker stuff. I first met him when I got to do visuals for him at this Wire gig. Cos I did quite a few visuals for the Wire events and in 2009 they did a three-day residency at the Vortex, the jazz club in Dalston and I was playing there every day. One of the guests that they had was James. I’d been really keen to do more stuff with him and we stayed in touch. There’s a project that he wanted me to work on; I really like his New Beat type stuff. I used to be really into New Beat back in my teens. There’s talk of doing that still. Once that project came up I was quite keen on doing it. He’s really nice, really chilled out [laughs].

"It’s kind of like the V/Vm stuff, it’s so different to what he’s actually like. That [noise music] is really full-on. Full-on plunderphonics. He did loads of that back in the late 90s, early 2000s, and it’s really extreme. But when you actually meet him he’s not like that at all. He’s more like what you would guess from his Caretaker material. Although the later volumes of Everywhere At The End Of Time are pretty noisy, I find. Have you heard the more recent ones? I think from volume 4 onwards it starts to get a lot more brutal."

Before we wrap up, I’m interested to learn about how he sees himself. He’s expressed distaste for the term “VJ” in the past, and tells me that he doesn’t identify as an artist.

“I really do think I interpret a brief in a very artistic way, but I think a true artist would just get up and be like ‘Oh, I’ll do this painting.’ But I don’t get that at all. But if I get asked ‘Can you do video for this or that’ then I interpret it in a completely wild way. But I need something to trigger that, whereas I think proper artists would probably not need anything. Does that make sense? I think a lot of people kind of label themselves an artist just because they do funny pictures on their computer or whatever, but I think that’s maybe a bit too easy. I think there’s a time and a place to say that you’re an artist. Another creative director pointed out to me that when you do a pitch or do a commission for something, if you call yourself an artist you can add another zero at the end.” He smirks. “So to clients I’ll probably say that I’m an artist.”