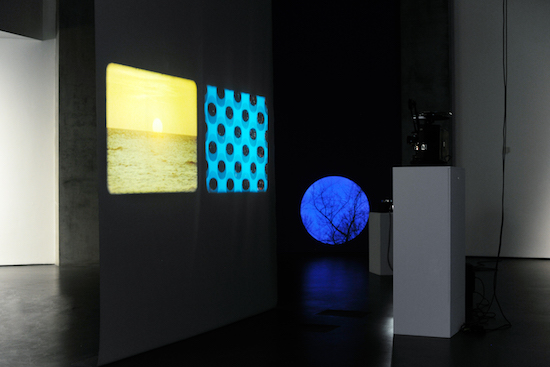

We stared at the Moon from the centre of the Sun, photograph by Alison Bettles, 2018

The world is a circle…

… and nobody knows where the circle ends. Two contrasting spaces on the ground floor of the Towner Gallery: one is moon-dark, the other sun-bright. Each contains work from the Arts Council Collection and the Towner’s own stock selected by Haroon Mirza. His chosen medley is not a dry scholastic affair. Mirza is not content to have these paintings, sculptures and videos displayed in a tediously linear approach. He seems unimpressed by standard showboating curatorial strategies. Mirza is more interested in doing something overtly theatrical, a game attempt at creating a gesamtkunstwerk of sound and vision constructed out of other people’s work with his own sonic and luminary interventions.

The show is called ‘We stared at the Moon from the centre of the Sun’. Mirza takes it as read that these orbital bodies are symbolically loaded in the grand scheme of human concerns throughout the millennia. But I doubt he wants you to dwell on all that jazz for long. This is an overtly sensuous show. You are here to enjoy a dance, a waltz of sorts through tracts of murk brightened by intermittent shafts of sharp lucidity. The lights here really do go on and off.

Deliberately there is no fixed starting point. There are fitful bursts of loud drone sounds. In the gaps of silence, dizzied by staring at so many round forms, you find yourself reminded of a Burt Bacharach tune from Lost Horizon (1973), a song that insists gnomically that:

The World is a Circle without a beginning and nobody knows where it really ends

Everything (in life; at this show) depends on where you are in the circle. We choose the gloom first. The eye rushes in recognition to Patrick Caulfield’s Dining Recess (1972) – one of his better-known canvases depicting a simple domestic scene – a table surrounded by some Saarinen ‘tulip’ chairs. But it is the lamp above the table that drags you in like a moth because Mirza has this brilliantly lunar lit by a single spot. The everyday is thus transfigured with economy, rendered numinous and reminds us of pictorial strategies beloved by the great religious painters. Beside this is Seamus Nicolson’s Megatripolis (1996), a C-type print featuring different type of worshipers – a crowd of ravers giving it large – at the famed London underground club from the mid-nineties. The spooky red retinal reflexes of the dancers reflect outwards as if they were so many alien life forms.

Elsewhere in the dark half Jonathan Monk’s restful Blue without Hidden Noise (version 2) (2017) is a slide installation showing circular images of bare wintery trees on a deep blue wall painted backdrop. As is his want Monk nods to conceptual forebears – Duchamp of course but specifically here to Douglas Huebler’s Duration Piece 5 (1969) in which Huebler took photographs of where he thought he had heard bird song in Central Park. The Monk revision, though, evokes a pleasantly prolonged gloaming.

We stared at the Moon from the centre of the Sun, photograph by Alison Bettles, 2018

Peter Fend (master of the deliberately futile gesture intended to highlight environmental catastrophe) is here with European Flag (1992). The work appears to be exactly that, the famed blue banner going round and round on a turntable. But those are not yellow stars, what we see are apparently maps of water drainage basins. There’s another set of decks sitting beside the Fend – the disc this time being Richard Wilson’s Watertable (1994) – a record of gurgling ground water sounds. These were recorded from an installation shown that year where Wilson had a full size billiard table placed in a hole excavated in the floor of Matt’s Gallery. A concrete drainpipe, like a giant pocket, was sunk through the table into the ground until it met said water table 4 metres below.

One of Peter Sedgley’s op-works Corona (1970) pulls you in hypnotically – a luminescent canvas with kinetic lighting that throbs psychedelically like a pulsating Kenneth Noland target. George Barber’s Arts Council GB Scratch (1988) amuses – it being a one minute and thirty-four second video featuring a repeated clip of David Hockney talking about Carl Andre. “Back to the bricks,” he babbles – the mix recalling the early cut-ups of Steinski such as The Motorcade Sped On (1987).

There are two more films in the dark room shown in tandem. Lis Rhodes’ short Dresden Dynamo (1972) was made with Letratone stickers applied to the film itself and the result is an effect where, in the artist’s words, “the image is the soundtrack, the soundtrack the image.” And Tacita Dean’s The Green Ray (2001) is a film of the sun setting and that putative phenomenon of its last rays, the green light. This is a work of faith. I couldn’t convince myself that I’d seen it.

Mirza’s groovy dark room selection calls to mind the images of Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable with those Danny Williams’ light innovations or stories from London’s UFO club in the 1960’s starring the Syd Barrett era-Pink Floyd. With the Floyd in mind it was time to move next door and ask – let there be more light.

The sunny side was, well, not that up really and came as something of a gentle let down – maybe you should see this room first. There are more circles in another Patrick Caulfield, Sculpture in a Landscape (1966), which seems to be referencing a Barbara Hepworth type sculpture with its big Swiss cheese holes. Here too a pair of works by Rose Wylie, England’s anarchic elder to Germany’s similarly inclined Jonathan Meese. The faux naïf Girl on Liner and Rose Wylie, Size 8: Orange (both 1996) may perplex. But sitting in judgement you are again made aware of that Bacharach ditty. Just because they may appear weak you need to consider that, even if you are partly right, at least you’re partially wrong. To someone else they are strong. Because the world is a circle without a beginning…

We stared at the moon from the centre of the sun: Haroon Mirza curates the Arts Council collection is at the Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, until 3 June