Girne harbour: I only wanted an ice-cream. Boats pulled to dock; the familiar sight of men who urged from restaurant doorways you drink their cooled beers ahead of others; sweet smelling nargile for sunshine liberals. The crowd swelled. Larger than usual. Shoulders pressed to backs, it proved difficult to navigate. In its centre a billboard stretched, its length blanketed beneath photographs of the civil war. The familiar black grain of the early 60s. A Turkish woman lay clothed in her bathtub. Three young children beside and on top. Blood soaked the side of light coloured bathroom tiles. An elderly man wept in another, beside charred remains. Another, a woman cried. Now, a row of men. Second from the camera, his head cut sharply in two by axe. Brain spilled across floor, manure pushed into open head. Fingers with holes where skewers had been forced, as well as abdomen.

This is not how I wanted to see my grandfather. Hands that didn’t know him (or me, or my father standing beside) touched the image. Disbelief. How could this happen to a person. Some cried. Others took photos of their own.

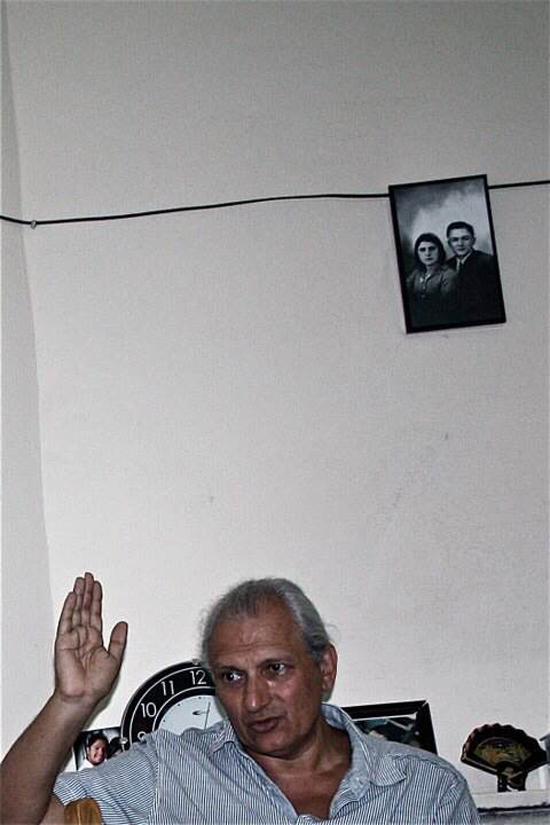

We have talked about it, this photograph and the events surrounding, in repeated detail. At dining tables, from chairs dragged into garden sun. Between food and fortune-read coffee, there is no difference between this family and others who reminisce, spirited, by family events.

My father recalls his mother behind the door with a sword. Her five children (dispersed equally between 2 and 15) beneath beds when soldiers came. "Stand outside," my father would tell her, "it is easy to shoot blindly into a room. Let them see who they are killing." This guidance, wildly older than the years of its speaker, could come only from a boy whose night hours would keep him on duty with a gun. One that would be replaced during day, in sad contrast, with plastic toy counterpart.

He was right; as much as to say no one would shoot them like this. Walked into fields behind their home, his sister cried as they took from her a watch. A wire-fence proved high for a soldier to jump. Pushing it to ground, my father held it low for him. It should embarrass the man or, at least, reveal kindness where there was none. My grandmother understood Greek. Something they would not know, and so it was this that she heard: "Don’t do it here. Take them to the place we killed their father and kill them there." She would learn of her husband’s death like this. Later, in the safety of a relative’s house, she would smash plates against her head. But here, their escape would seem less dramatic. A British woman working for the UN (who my father simply remembers as ‘Margaret’) would stop the soldiers and remove the family to a safer place.

It is thought a British journalist later came across the body of my grandfather and his friends. That it was this unnamed elusive Brit who took the photograph. Though it could be these very dregs of colonialism that make connections between documentation and reporting as conclusively British. In the 90s when my father was still a radiographer (photography of a different kind, you could say), he x-rayed a Turkish photographer from Paphos who told him he had been the first to take the pictures from that time. Whether it had been him who captured specifically the image of my grandfather remains unknown.

The original picture has length. Perhaps thirteen men, side-by-side, blood spills from heads and mouths. We are related, in some manner or another, to many of them. Cousins by some default. The youngest to be seized, an eleven year old boy (at this time, my father’s closest friend), would not be in the picture. Taken to hospital with an injured shoulder, his blood would be fully drained and it was here that he would later die. His mother, a woman I know only as small and slow to walk, would lose son, husband, and father on this day.

You could say they knew it would come for them. In Kumsal, a suburb of Nicosia, riverbeds dried. Red clay cracked where geraniums grew in summer months. Here Nihat Ilhan, a medical officer, was on duty away from home. Some three months before my family’s outcome (which had been on the other side of the island in Paphos), Nihat’s wife and three young children took shelter in their bath when bullets first sprayed outside walls. A photograph described at the start of this piece would reveal their fates.

This image, much like that of my grandfather, found synonymity with the war. Their home opened instantly, morbidly, to the public. A mausoleum of sorts, more specifically the Museum Of Barbarism (which still remains). As the West turned attention away from the fighting (later history would claim that Turkey invaded in 1974, as though Turks were not born or living on the island some centuries before), such a space was needed. It would act as their collective sanity. Here they would document each atrocity their community incurred from as early as the 50s. Proof, they thought, if the world one day looked.

Red geraniums still grow neatly from pathway to front door. The bathtub the same. Blood, though faded, is as it appears in the picture. Where photos of family once decorated living room walls, images of the war’s cruelty now replace them. It would be here in 1965, a little over a year since his father’s death, that my father, then 14, would visit. By now his father had become venerable. Stories of their outcome that day (13 men who lived in their village, cornered by Greek soldiers and eventually taken to a pig farmers house: my grandfather, tortured severely for looking the most Turkish) would be told as legend. Some details were true, others less so. The photograph had been seen by some, though naturally the children would be led to believe there was a troubling image circulating of somebody else.

In what had, only a year prior, been Nihat Ilhan’s home, my father described the trauma in the house at this time as ‘fresh’. In a room to the right of the bathroom my father knew the photographs would only get worse, yet never expected his father. For a while it would be removed from the museum for being too graphic, too upsetting to witness (since, it has been put back). Some years later my father would return and ask the curator for access to it, where he then photographed the image for himself. (In a similar, but sadder, twist my father would share a taxi with a group of men the following year. One would, unknowingly, speak of being present for the torture and murder of his father and would go on to describe it.)

In stark contrast, I had seen no other image of my grandfather until I was 14. I knew no other sight of this man. The picture was hard to lose. In London’s Haringey, we returned home with Turkish newspapers. An annual 9 March obituary spread the image across front pages: "Never Forget" this yearly headline read. It was, frankly, impossible to. I remember, as a child, my father at our kitchen table with the image. He would scan over it, sometimes for hours at a time. He admits now he wanted to study the last moments, to work out exactly what had been done to these men. Only once he knew, could he put it to rest.

In later years, the late 90s, under European influence the papers would begin to censor his face. It smoothed the shock for bystanders who claimed the image for their own vindication, yet neglected the families by continuing to publish it. Ironically, even such blurring overlooked us; his face was the only part I wanted to see.

Back in North Cyprus some ten years later, young men began their national service. They ate from transported metal barbeques their families brought to the grounds outside barracks. Beneath pine trees, meat already tacked to skewers were thrown to heat. Soft drinks and water bulked old coolers. There were hundreds of us. These nervous boys, and their families who had come to unwillingly send them off. It would happen that the grandson of the man in the photograph beside my grandfather would start his army service this same day as my cousin. Eating with his family in the shade of a tree beside us, both boys were named after their grandfathers.

"I don’t eat," my cousin whispered to me once from a phone smuggled into the training camp. "They have our granddad’s picture on every wall. It is a reminder, they say, for why we need an army. I can’t eat. How can I, when our granddad is hanging dead over my soup? He is war for them. They can’t imagine what he is for us."

It is true that every history book I own on the war – those with photos of him within their pages (there are many) – I keep from sight. Not in boxes – I couldn’t bear that – but on shelves in corridors, or rooms I do not spend much time living from. Yet, growing up with this image was not always as morbid as it should sound. You see, he was just a face. A man who, if you ignored the surroundings, looked as my father does from that angle. Perhaps even my cousin. It was context. My ability to view him as nothing less than a man. This comes, even to this day, with self-preparation, a choice for when I view it; to understand him as part of my family, as one would their own family photo albums. But standing in afternoon sun, desiring ice-cream, was not the time. Nor was it our choice; we were not prepared. Hands that touched and looked with curiosity, or pity, rage they could take as their own, forgot, quite plainly, that for some of us he was not politics. Really, only a grandfather.

It is a logical step in my mind to have grown, almost obsessively, a fascination with Don McCullin. Hours lost to the internet, scrolling (often repeated) images he had taken of war. I must admit, I was hoping to find my grandfather amongst his work. For a time, perhaps to this day, I fantasised it was McCullin who had taken the picture. This man whose work I admired, who respected conflict through composition, searched for beauty where it lacked. I hoped he might be the last link between us and my grandfather. A happy ending, if you will, where there was none. McCullin, I thought, would become the component between the dark space that sits between man, and corpse. What I needed – in fact, what I still need – is to believe that the photograph was not taken gratuitously, but with some semblance of humanity. If my grandfather were to be known, let it be for art, and not for everything wrong in the world.

McCullin’s exhibition at the Imperial War Museum (2011), displayed photos he had taken from the Cyprus conflict through the 1960s. A striking image of a woman cried and clutched her hands to her chest. Along another wall, a sequence of three captured the same incident. Between a narrow road, arched window shutters, an old tank to the right of the picture. To the left, three men stand with the side of a house for shelter. One wears a long rain coat, peaked hat. At the front, in a dark suit, a man leans forward, his hand grabs a body in the road.

At home I logged into Facebook, sure I had seen this before. My father’s cousin, an older man who runs a chain of successful shoe shops, was tagged in one picture. Beside the image, it read: During the Turkish – Greek fighting in Limassol on 14 February 1964, an English armoured vehicle is trying to provide cover for 3 Turkish Cypriots trying to pull their friend to safety. Each name connected to the men’s social networking pages. The man in McCullin’s photo, dark suit, reaching, grabbing his friend in the road (as Facebook would confirm) was this same man whom I had often bought sandals from. Shoe shops from where, rather wonderfully, he had once begun as an apprentice to my grandfather who had shared the same profession. It seems silly to say, I cried with relief. Though it was not entirely the outcome I had invented, there was still some great link to what I imagined. I don’t suppose the need to find who did take my grandfather’s photo will ever fade in me, however, a piece of the puzzle, I felt, almost fitted.

This form of social networking opened an evolved world for these photos. ‘Groups’ were created where those who had fought, and equally lost, in the war could share these memories and their accompanying image. It was a form of communal therapy. In all cases it was invaluable to have. Yet, it became even harder to escape my grandfather’s photograph when boredom had only brought me to scroll through friend’s nights out and schoolmates weddings. Soon into writing this, my mother called with a warning: "Your granddad’s picture has been redone with colour. You can see, well, everything, so clearly. I thought you mustn’t be surprised." It is always a surprise. No matter how often, or how old. There are dilemmas: will I show my own children when I have them one day? What will I say?

I don’t know if my grandmother ever saw the photograph. I never dared ask. At her funeral in 2011, her nephew simply said, "It’s not yesterday she died, but 47 years ago." That much was true. Her road, the street name on the lamppost facing her front door, still reads Şehit Süleyman Recep Sokak. "Şehit" to mean martyr, "sokak" as road; between, her husband’s name. Her house too would be a peculiar place. Whilst it never opened to the public, it would share many of the features of the Museum of Barbarism. Walls, inside as well as out, caked in bullet holes. Window shutters the same. In her bedroom, stained in stone floors, a large bloodstain that could not be washed out. We played as children like this. The stories of dead bodies buried in her garden were instead challenges we wanted to dig up (we didn’t get remotely close, and scared ourselves soon into it). This was how we lived in a post-war country. One still in cease-fire. We learnt faces from dead photographs, and drove toy cars over blood. Human nature finds normality where there should be none.

A plastic clock and calendar hammered into one wall. A football shaped stain where a ball had been kicked against fresh paint. I was 14 when an old friend of the family appeared with a photograph assumed long gone, lost the day they were taken into a field and never allowed home. Rescued from their burnt down house, in a broken glass frame. My father is three in the picture. A curious, unimpressed look. Facial expression remarkably close to a photo of myself, full of berries in 1986. Beside, his sister holds a toy. My grandmother, long black skirt, her hair uncovered, unlike how I remember it growing up. She is perhaps only 21 here. Beside her my grandfather rests his hand on my aunt’s shoulder. More than likely to keep the children facing toward the camera. This family friend would eventually, after a long time, locate my grandmother, wanting for the photograph to be returned to the family before she died. A few months later this woman would indeed pass away.

It made it, eventually, on to my grandmother’s wall. As time went by other photos emerged. My grandfather and one of his brothers. My grandmother and her husband.

For a long time these scared me the most. No longer an allegory of war. No one could capture these photographs and show them when and where, or how they wanted; for their own thoughts and gains. Proof – if it were ever doubted – that he was once alive. That he was ever alive is sometimes far harder to understand. Or imagine. I suppose it shouldn’t have mattered. Finally, he was just a man.