Kenny Schachter Voice Gem

Growing up on a council estate in East London, the young Harry Yeff wasn’t sure if he’d ever find a voice. The multidisciplinary artist known as Reeps One for his music, and Reeps100 for his more variegated visual-based projects, comes from what he describes as a neurodivergent household – both parents were on the spectrum while he is dyslexic and has been diagnosed with ADHD. “I had a happy childhood,” he says, “but it was tough.” As a teenager, Yeff started beatboxing and uploaded his first video to YouTube in 2010. He now has approximately 195K followers on his channel and some of his posts have received more than five million hits.

Intriguingly, his preferred style of music growing up wasn’t grime as much as it was weird electronica: Aphex Twin, Autechre, and other left field artists on labels like Warp and Rephlex; capricious music that can swing from ambient drones to 210 bpm in a tachycardial heart beat. His ability to imitate glitchy electronica and channel this punishing music so effectively marked him out as different and attracted the world of academia and neuroscientists like Dr Sophie Scott at UCL, who has observed Yeff’s cognitive patterns to better understand how the brain works.

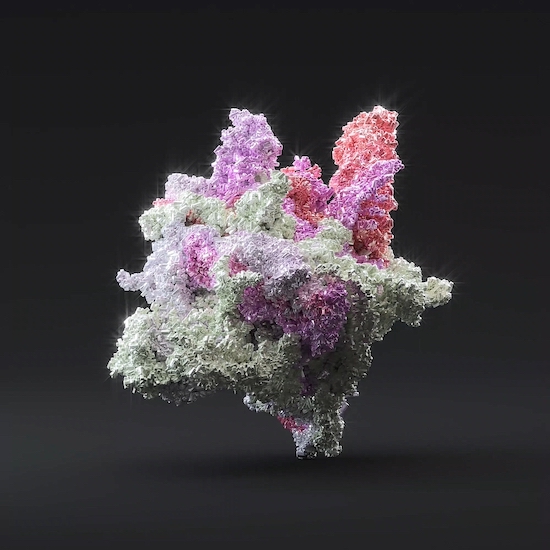

The artist’s dedication to the voice and its potential has opened up avenues of opportunity, from TED talks to a role at the World Economic Forum. And then there’s Voice Gems, created in collaboration with Hanoi beatboxer and visual artist Trung Bao. It’s an ongoing project – so ongoing that it purports to be designed to last 1,000 years. The “Earth’s most unique, remarkable and vulnerable voices” are being collected and stored in a digital realm, generating objects that seemingly build themselves from vocal stimulus. Yeff has been catching and collecting voices like a lepidopterist over recent years: Ai Weiwei, Dr Jane Goodall, Yogi Sadhguru, Lily Cole and Sir Geoff Hurst are a few voices among hundreds. And as it’s an ongoing project, there is scope for many more in the future, and more exhibitions too.

Yeff tells me he recently received a moving tribute from Hurst to his 1966 England World Cup winning teammates, many of whom died of Altzeimer’s. The disease has been linked back to the heading of heavy, waterlogged footballs – an occupational hazard before polyurethane-coated balls were introduced in the 1980s. Hurst and all of the other contributors have been requested to speak for one minute, and then the process begins. “When we receive that recording, we place it through what’s called the Voice Gems System, and the piece works on fingerprint-like information from the voice data. And that generates the unique gemstone that can become a large-scale digital piece or a physical sculpture.”

According to my own observations of these shiny objects, which appear to be suspended in black monoliths of space-time, Ai Weiwei’s Voice Gem resembled a plump, exotic bird, while Hurst’s is upstanding like a meat carcass doused in glitter. To the lay observer, it’s impossible to begin to comprehend how the software created by Yeff and Bao takes data and converts it into an object, or why it chooses certain colours, though Yeff says the Voice Gems System is bound by strict rules and goes through what he calls a “digital ceremony”. A voice put through the same system twice would create the same object.

Harry Yeff Speaking at Davos

Arbitrary to the observer or not, these digital objects seen collectively in a basement under a shop on Oxford Street, are certainly worth looking in on. The drone soundtrack, coming through speakers suspended all around W1 Immersive, is created from hundreds of voices from people who’ve sent messages electronically, eliciting a meditative, digital Bardo Thödol. Undertakers take note: it could even be an inchoate form of virtual headstone. Most of these contributors are still with us, and yet the sensation of impermanence is palpable.

Yeff is keen to capture dying languages and voices of critically endangered species as a preemptive act of preservation. I mention O’o, a wonderful Barcelona-based French band signed to InFiné who took their name from the Hawaii Kauaʻi ʻōʻō, extinct since the late 80s. The bird’s haunting and distinctive cri de cœur can be heard with just a cursory search on YouTube. Could Harry preserve the ōʻō in a Voice Gem? “I could, but there’s a rule,” he says. “One of the key rules is that I will never make a piece unless there’s a direct connection to the person or the audio that’s been sent. People suggest ideas all the time, but to me being strict with it is why I think it has integrity.”

It’s telling that Yeff is keen to talk about blockchain technology rather than NFTs, which the Voice Gems are created in as well as through other technologies. If we’re talking about a project that’s meant to last a thousand years, then NFTs may peter out quicker than the thousand-year Reich. More tangible ways in which these Voice Gems are preserved include 3D printing – done in resin, and occasionally in silver and gold – in case the virtual world disappears. If conceptually, Voice Gems is still in development, then Yeff’s evangelism for the human voice comes from a deep grounding in theory and praxis (Gladwell’s “10,000-hour rule” has been more like 30,000 hours of dedication so far, according to the man himself).

VOICE GEMS at W1 Immersive

“We on average use about 20% of what our voices can actually do as English speakers,” he says. “When you look at linguistics and phonetics, globally, we’re discovering new pressures all the time.” There are apparently 44 phonemes in English, though linguists estimate that the world’s languages use 800-plus phonemes. Furthermore, Yeff likens expanding the voice and pushing its capabilities to stretching or exercising, and suggests greater vocal control improves wellbeing and ameliorates communication and engagement too.

If the average person uses 20% of their vocal capacity, then how much does someone with a six-octave vocal range like Mike Patton use? Yeff, it turns out, has an association with the on-off Faith No More frontman, first established when Patton went to see him play live in Reading eight years ago. He’s “a big voice in the voice family”, says Yeff, who has performed with Patton on occasion and consulted him in matters of the vox. “He has this deeply cathartic, experimental nature where he’s like: ‘I’m just gonna unleash!’ And it’s not necessarily that he uses 100% of all that is possible, but he’s stretching everyday, thinking about his shoulders, thinking about his hips, thinking about his feet… He’s really interested in what his potential is. And he’s also deeply fascinated by other people that go on that journey. And that’s why we connected.”

Yeff says it’s impossible to express in a percentage how much of Patton’s voice he uses, but it’s “way above what the average person uses.” Then he adds: “All of this shouldn’t be new. And it shouldn’t be strange. The voice is the body. People forget that.”

Voice Gems: 1000 Year Archive is at W1 Immersive, London