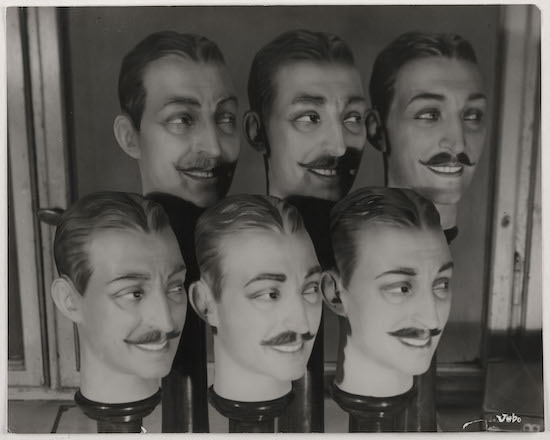

Umbo, Ohne Titel (Menjou en gros), 1928/1929, Leihgabe der Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung

© Phyllis Umbehr/Galerie Kicken Berlin/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020, Repro: Anja E. Witte

“Are the Nazis Coming Back?” No – not a recent headline about far-right murderers in Germany, or the machinations of the AfD, but the title of a sequence of photographs taken as early as 1951 by Umbo. Here are individual portraits: a balding be-suited businessman with a pen clipped to his jacket pocket and a cane held threateningly under his arm; the hangdog features of a Nosferatu-like thug called Fritz Dorls; a finger-pointing goon in a loud dog-tooth cunt jacket. Umbo is telling us – if it looks like a Nazi, acts like a Nazi, dresses like a Nazi – then it’s a Nazi. His warning is timely. This show in Berlin features a cross section of what is left of his work; tens of thousands of prints were destroyed when his studio was blown up in 1943.

Born Otto Umbehr in Düsseldorf on January the 18th, 1902, Umbo got his first camera when he was thirteen. Aged nineteen he gets into the Bauhaus and trains under Johannes Itten. Itten (something of a genius) was a fad-mad obsessive into breathing techniques and… plums. Apparently he was riled by Umbo’s unpunctuality and, weirdly, took against his student’s thumbs as part of some bonkers eugenicist rant. Umbo was thus the first student to be expelled from the school. But he had absolute respect for Itten’s teachings and said later: ‘I had no idea about technology but I had learned one thing: composition. And this from Johannes Itten at the Bauhaus.’

Umbo comes across as a kind of Huck Finn figure, resistant to being ‘sivilized’– an anti-bourgeois bohemian wanderer who slept in the woods and lived a life of purposeful laziness. But he was also a poet of curiosity: look at it this way, not that. By 1926 he’s in Berlin and kipping in the Tiergarten – he’s looking at the city’s ripped backsides, getting a heat by riding on the Ring-Bahn. At the Romanisches Café he collapses through near starvation.

And then his photography takes off by getting into magazines like Alfred Flechtheim’s legendary art journal Der Querschnitt. He’s not about technical expertise – it’s about seeing things anew as with his Sinister Street (1928), where we look down on some elongated odd dark forms on the pavement that turn out to be simple shadows cast by the sun.

Other professional photographers on the Kurfürstendamm were soon envious of his quick success. Much of this was due to the popularity of the shots he took of actress Ruth Landshoff – the bisexual cross-dressing star of the day. He was keen to use the most flattering features of his sitters: we see Ruth peering out from a dark Fantômas mask, her mouth opens showing her gleaming white teeth. In another her chin rests on a delicate hand, her dark eyes look up at us in a questioning gaze. And in The Hat (1927) the black shapes of her eyes and the cupid’s bow of her lips contrast starkly with the bright pallor of her skin in an image that prefigures the iconic cover of Lou Reed’s Transformer (1972).

Umbo, Ruth Landshoff, 1927/1928, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau, 2016 © Phyllis Umbehr/Galerie Kicken Berlin/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

By the end of 1928 he’s working as a photojournalist and close to the heart of the Expressionist/New Objectivity movements. He has a brief collaboration with the brilliant but doomed Yva (1900–1942): “I went to her because I had some idea of what I fantasized should be possible to translate into photography and I explained that to her.” He masters the close-up; becomes a great cropper.

And so we see the dancer Valeska Gert, her stark features a Noh-like mask. Then there are the decadent scenes of nightclubbing as with Conversation in the Night (Willi Wolpe and Tanja Tanjewsa) both images from 1927 – a couple who look like Tracy Pew and Lydia Lunch on a bender. His portraits of Ruth Cidor-Citroen (1926) and the artist Kolja Wassilieff (1928) are like the source material for one of Christian Schad’s contemporaneous near-photorealist paintings. Then there’s Umbo’s terrific photomontage The Raging Reporter (1926) – an image of the journalist Egon Erwin Kisch. We see Kisch as a mensch-machine with his camera eye, ears like phonogram speakers, a typewriter torso, all fountain-pen arms and a leg like a bi-plane, as he strides across the city in search of the story.

Umbo’s own Self-Portrait (c. 1930) catches him sunbathing; his round hipster shades could be from this century. And then too his showroom dummies, those disturbingly mute mannequin’s like Smiling Woman or Menjou en gros, both from 1928, the latter being a proto-surrealist line of disarticulated male heads. The hauntingly sparse photograph Leaving the Allotment Garden for Home (1934) recalls the railway scenes of another painter, Georg Schrimpf. Umbo’s influence was mighty: In the Turbine House (1934) predicts the industrial fascinations of Hilla and Bernd Becher.

His income plummets after Hitler comes to power and the magazines close. He stays in Germany and works for a Wehrmacht propaganda outfit that sees him with Rommel in Libya. His post-war imagery is denuded of fun. Untitled (Still life with an Eye) (1948) is a spare surrealist image with a sad back-story. The eye is false and it’s his: he lost his left one in an accident doing restoration work.

Life after looked grim. We see the victors, the invaders, as with a sternly disapproving couple – Americans with a Pram in Steglitz (1950). Then there’s the destruction on the ravaged island of Heligoland as with The Centrepiece of the Cemetery Plowed by Bombs (1951). Elsewhere we see refugee children with their faces pockmarked with impetigo, and with The Man in the Zoo series (1950) we catch a glimpse of one of Europe’s last hunger artists. Umbo didn’t flinch from referencing his country’s crimes: here too are his Bergen-Belsen shots (1947) of survivors in rehabilitation before their emigration to Israel.

Umbo began his career as the great experimenter and ended it like W. Eugene Smith, a photo-essayist majoring in the pity of life. He knew only too well how it could turn upside-down. But his philosophy remained simple: ‘I love things’. He died on May 12, 1980, in Hannover. Pleasingly, he lived long enough to see a significant revival of interest in his work.