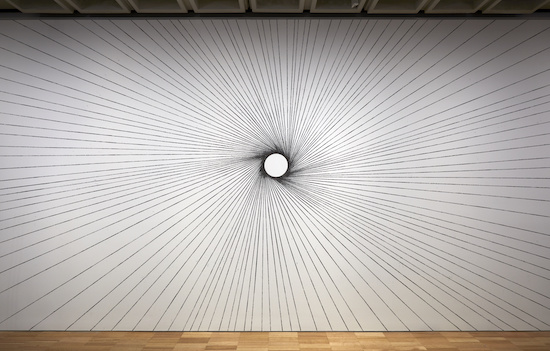

Sandra Selig, One Rotation 2019, charcoal on existing wall, digital audio recording, 340 x 3,187.9 cm. Courtesy the artist, Milani Gallery, Brisbane, and Sarah Cottier Gallery, Sydney © the artist. Photo: AGNSW, Diana Panuccio

A woman removes her shoes and then clambers with care onto a platform. She lowers herself flat and places both hands to grip the edge of a makeshift stage. Looking up at the audience taking photographs of her she opens her mouth in fake panic. Behind her a large screen shows an aerial shot of a busy city street, seemingly far below.

This is a work by Nat Thomas, a Melbourne-based artist, called Postcards from the Edge (2019), that references a scene from the 1989 movie of the same name based on the book by actress Carrie Fisher. Thomas is one of more than sixty artists shown here in The National 2019: New Australian Art, a three-venue roundup of current practice from the continent. We may be tempted to read Thomas’ contribution as a metaphor for Australia’s position in the contemporary art world: insecure, a persistent worrier suffering from a high anxiety panic that the country is too distanced from received notions as to where the current centres of artistic innovation might exist; scared that local ideas might fall flat in the rush and crush of faster, flashier, cultural traffic. But such a reading would be overly pessimistic; there is plenty of ripper work here.

Art by indigenous peoples is generously represented and some of it subverts clichéd expectations of deep spiritual import. There are the canvases of Kaylene Whiskey, for example, an artist who works in a remote region of South Australia, that depicts faux naïf images of American stars like Dolly Parton and Cher thus pithily – and amusingly – commenting on the impact of popular culture on her isolated community. Whilst celebrating the glories of Western pop music, Whiskey is alert to the downside of life on the other side of the Pacific: she warns of the risks of diabetes from drinking sugary soft drinks – a real health issue for her people.

Elsewhere we see works by Mumu Mike Williams, a more obviously political artist long active in the Land Rights movement. He paints on repurposed canvas mailbags, government property that he delights in appropriating. His work highlights the contradictions between national and Anangu law. Sally M. Nangala Mulda is another painter who adds text to her local scenes that outline the horrors of alcoholism and police oppression. There are more apparently blithe works by Daisy Japulija, Sonia Kurarra, Tjigila Nada Rawlins, and Ms Uhl of the Western Australian Mangkaja Arts collective; acrylics on Perspex hang vertically in the gallery space and are abstractions of great beauty worthy of a Helen Frankenthaler, each fecund with associations to the at-risk natural world.

Kaylene Whiskey, Installation view, The National 2019: New Australian Art, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney Image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist Photograph: Jacquie Manning

Colour is big at The National. Australian artists do not have to look far to see it in the everyday. Eric Bridgeman’s assembly of multi-patterned shields, Sikiram/Büng/Scrum (2019), references traditional warrior protection but also, more prosaically, rugby jerseys. His mass of diamonds and stripes and parallelograms are as brash as a jinking flanker.

Australia’s various immigrant communities are also well represented. Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s wonderful Pretty Beach (2019) is a sculptural installation of wooden stingrays found on the floor; above we see crystals attached to silver plate chains that simulate rain. We learn that the scene is a recapitulation of the artist’s memories of his Malayan family. James Nguyen’s video contribution, Portion 53 (2019), features his father revisiting the site of his first residence in Australia, a refugee camp where South Vietnamese were placed after escaping the communist takeover. But long before those traumatic events, the camp had been the site of one of the first recorded indigenous land claims. Nguyen thus suggests that more recent immigrants might also be implicated in the displacement of First Nation peoples.

Then there are the European immigrants. Eugenia Raskopoulos is from the Czech Republic and shows (dis)order (2019), where we see a projected video of her atop a forklift truck. She lifts a series of household objects from a tall stack only to coolly toss each to the floor. A real collection of microwave ovens, kettles and toasters lies on the ground in an angrily stark rejection of domesticity, a gesture of fuck-you feminism. Similarly Tara Marynowsky’s video installation Coming Attractions (2017–19) is an acerbic #MeToo comment that features movie trailers she has altered by scratchings somewhat in the manner of Stan Brakhage. The female stars of the likes of Indecent Proposal (1993) and Pretty Woman (1990) are literally defaced.

Abdul-Rahman Abdullah, Pretty Beach 2019 Installation view, The National 2019: New Australian Art

, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney painted wood, silver plate ball chain, crystals, audio

Image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist Photograph: Jacquie Manning

More blasts of near-psychedelic colour arrive with Sean Rafferty, an archival artist from Galway and now based in Brisbane. He previously worked in grocery stores and Cartonography (FNQ) (2019) is his collection of brightly coloured fruit and veg packaging from Far North Queensland as flashy as a flight of lorikeets. Rafferty sees these cartons as modern coats of arms for the farming families and a reminder of the various diasporic communities they represent.

Finally two personal favourites. The Rapids (2019) is a video by Tina Havelock Stevens that sees the artist drumming in a jungle setting. We learn that this is where Francis Ford Coppola filmed Apocalypse Now (1979) and glimpse the scene where the young Mr Clean clatters his drumsticks thus threatening to bust the balls of the clearly irritated Captain Willard. Stevens is a mean player herself and the images of her thumping the skins are spliced with shots of tumbling rapids and the destruction these can cause. There are not enough works in contemporary art that feature drums; Stevens’ is a welcome contribution.

Lastly there’s Cherine Fahd’s work Apókryphos (2018–19), a sequence of photographs the artist obtained that feature her family at the funeral of her grandfather. Fahd was only aged two at the time. Here she bravely amends the shots with her own interpretations of the mourners and their frozen actions. Fahd daringly encourages our voyeurism, our desire to make up our own fictions around the tableaux of grieving. Australian art might not be free of worry but much is in robust fettle.

The National continues at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until 21 July