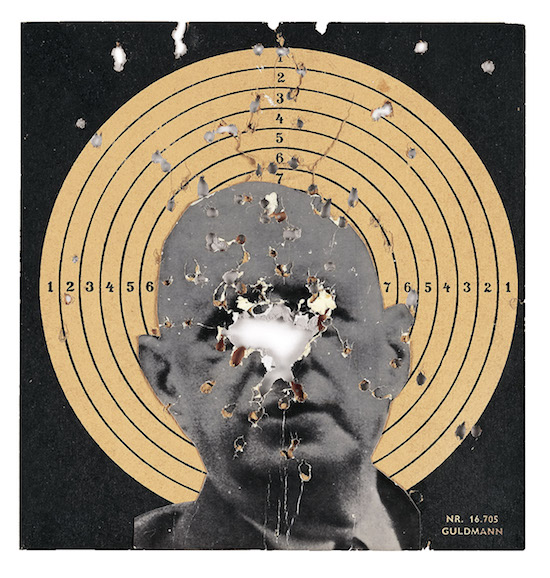

Untitled, Dartboard-collage from the exhibition Destruktion af RSG-6 at the gallery Exi, Odense, Denmark, 1963, Courtesy Private Collection

The venue is certainly spectacular. On a bend in the Spree sits the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, a gift from the USA to what was then West Berlin, a conference hall designed by the American architect Hugh Stubbins. The locals call it Die schwangere Auster – the pregnant oyster – and it does look a bit like a marine bivalve, even if the exterior is said to reference the crown on the Statue of Liberty.

Liberty and freedom – that’s what we are told the Situationist International (S.I.) and their leader, the Parisian Guy Debord (1931-1994), were all about, even if they despised America and all it stood for. At HKW we are presented with a survey of their thinking in a show called The Most Dangerous Game. They were anti-authoritarian pranksters hypercritical of the mass media, the Spectacle. They had no time for advanced consumer capitalism.

So why has their spiky provocation, their playfully innovative thinking, become so quickly domesticated? How has their example of charged insolence been rendered tame and coddled by lame stunts like that perpetrated by Banksy at Sotheby’s recently?

Recuperation, in a word. Debord’s radical ideas have themselves been co-opted, commodified. As Joe Strummer once sang – himself no stranger to the risks of cultural appropriation, of sell-out to CBS Records – you think it’s funny turning rebellion into money. So HKW asks – what should we make of the S.I. today?

This fascinating exhibition begins with the Bibliothèque situationniste de Silkeborg, a venture drafted in outline back in 1959 but unrealized until now, in which the co-founders of the S.I. – Debord and the painter Asger Jorn – proposed a library documenting their activity and influences. This collection of books and pamphlets was meant to exist in Denmark. And here they are now, presented in twenty-one pristine vitrines.

Immediately you grasp the gag. This is a library where frustration rules. You can look at the covers but not read the books. Debord was into ephemera and disappearance; he desired oblivion and obscurity and loved the perverse idea of a library that could not be read. He was, if you like, the anti-Nabokov; his message was a shout of despair that yelled at the avant-garde: shut up, memory!

The first vitrine contains texts that had a key influence on Debord and his mates. Unsurprisingly there are inspirations such as the ludic poetry of Guillaume Apollinaire. Predictably too there’s André Breton’s surrealist manifesto (1924), some of Tristan Tzara’s dada pronouncements from 1921 and the appropriately entitled Homo Ludens by Johan Huizinga (1951). Debord was a player, a provocateur; the wind-up was his forte. The academic Vincent Kaufmann writes – “he had a precocious talent for invective”. As early as 1952 his team wrote a tract addressed to Charlie Chaplin, then escaping the McCarthy witch-hunt, that in part read “Get lost, fascist worm”. Charming…

Juvenile sniping at elders: the bracing dare of it all. We are reminded of Paul Cook wearing his ‘I Hate Pink Floyd’ T-shirt (Malcolm McLaren was a keen student of S.I. activity) or the Jesus and Mary Chain’s Jim Reid caught on a Dutch TV interview saying that Joy Division “were rubbish”.

I’d like to teach the world to sing in perfect harmony. You can’t escape hearing that advert for Coca-Cola in the hall. It’s the real thing. The tune is on a loop and the sickly video itself is spliced with a particularly gruesome excerpt from Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975). Here the S.I. brutally showed how that attractive youthful rebellious idealism, characteristic of the hippy years, had become besmirched, turned into product.

This juxtaposition is an example of détournement familiar to those S.I. inspired images from the punk era such as Jamie Reid’s designs for the Sex Pistols. Punk is also recalled in the editions of Potlatch, a magazine Debord was involved with from the 50s that preceded the S.I. These were cheaply made, like old copies of Mark P’s Sniffin’ Glue fanzine. The adversarial tone of Potlatch and its frugal production values also call to mind the vituperative ‘90s tabloid parodies of London’s BANK collective.

Debord made films, some shown here, that were coldly anti-cinematic and featured blank screens or deliberately scratched stock. He thought cinema was dead. There’s one edition of the S.I. inspired International Times magazine from ’68 here that has an amusingly détourned cartoon in which a woman tells Jean-Luc Godard – “maybe you can get the hippies baby, but you can’t get us.”

What of the revolutionary actions of 1968, said to have been partly inspired by the S.I.? We see photos of university occupations, street fighting men and women, President de Gaulle leaving Paris in an insect-like chopper, burnt out cars, folks chucking stones. As Debord sighed in later life – “ never again so wild”.

But as he aged Debord arguably sounded increasingly like a boring old fart bemoaning the break up of the Beatles. In 1985 he wrote ludicrously that “since 1954 there has never again appeared anywhere, a single artist of even the slightest value”. Indeed, the last section of the show features anti-art, anti-paintings, many by Jorn. The flea market landscapes over painted with smears recall the rubbishy tat sold by TV’s Reggie Perrin (a fictional S.I. member, if ever there was one) from his anti-business ‘Grot’.

Like the endless recapitulation of punk’s historiography in the senile wastes of Mojo and Q magazine the influence of the S.I. amongst the youth of today has become domesticated. We might even argue that the actual Situationists now, those who live by their more delightful precepts, are the gentler peers of those who flung paving stones back in ’68. As Debord scrawled on a wall in 1953: Ne travaillez jamais! The majority of the elderly punters walking around the HKW on this quiet Monday certainly don’t appear to be putting in the hours down on the shop floor these days. Later they might drift, go on dérive around the city centre in a psychogeographical trance that recaptures their lost childhood like those old codgers in that other (ahem…arguably) S.I. inspired British T.V. show – The Last of the Summer Wine. Debord would have hated them.

The Most Dangerous Game: The Situationist International en route for May ’68 is at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, until 10 December 2018