Sutapa Biswas, Housewives with Steak-Knives, 1985. Medium: oil, acrylics, pencil, collage, white tape on paper on canvas. Dimensions: 2450mm x 2220mm. © Sutapa Biswas. All rights reserved, DACS 2019

At the end of the first season of Netflix’s raunchy reality series Too Hot to Handle, which saw attractive singles living in a beachside Mexican resort attempt the purportedly herculean task of restraining their sexual impulses to win a $100,000 cash prize, the six final women participate in a ‘yoni puja’ workshop. ‘Yoni,’ a Sanskrit word, roughly translates as vulva, and ‘puja’ as worship. Yoni puja, the women are informed, is about “truly owning who you are in this very moment, feeling good about that, and drawing inspiration and power from it.”

Each woman stands naked in a wooden cubicle with nothing but a hand mirror, as an intimacy coach encourages the group to examine their vaginas, to vocally observe what they see before painting them. The women delight in the gimmick, giggling while struggling to pronounce ‘yoni puja’ (it’s not particularly non-phonetic). The paintings they create range from anatomically dubious to absurdist, and the whole charade inserts a dose of exoticism into the culture of individualist self-love off which neoliberal capitalism profits, and for which scripted “reality” television acts as an aperture.

Yoni puja is really a devotional practice from the medieval Indian philosophy of Tantra, and its appropriation on Too Hot to Handle exemplifies its constant misinterpretation in the West, along the same homogenizing lines that have charged sacred Indian practices like kama sutra with orientalist impressions of hypersexual hedonism. Tantra: enlightenment to revolution, a new exhibition at the British Museum that runs through 24 January 2021, attempts to add nuance and context to Tantra’s Western interpretation through an impressive array of aesthetic and devotional objects spanning over a millennia.

Tantra first arose around 500 AD, and its core assertion is that the material world is infused with divine feminine power. It’s derived from the sacred instructional texts, the Tantras, which offer insight into certain anti-establishment, transgressive rituals that – when carried out correctly, and with guidance from a guru – can grant access to this power, manifested both temporally and supernaturally, like longevity and spiritual enlightenment.

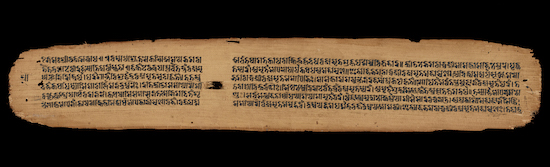

An early ‘Tantra’ from Nepal. © The Syndics of Cambridge University Library

The philosophy challenged orthodox Hindu and Buddhist bifurcations of the world into categories of sacred and profane, along with patriarchal understandings of the female body as an impediment to enlightenment. Instead, it asserts that women embody Shakti, the energy that comprises the entire universe. Tantra encourages veneration of the body in its many forms and states, often incorporating matter that might otherwise be considered taboo: alcohol, bhang, sexual fluids, blood, human remains.

The aesthetics of Tantra mirror this celebration of the flesh. Visitors cluster around objects with the highest Victorian shock-value – like a Tantric temple frieze sculpture carved of stone, with the dynamic, arched form of a woman receiving oral sex (an actual example of yoni puja). Then there are mithuna carvings of couples in erotic poses, which aren’t explicitly Tantric but evoke its divine sensuality: lovers caressing each other, lips suspended in the moment before a kiss.

Chamunda dancing on a corpse, Madhya Pradesh, Central India, 800s. ©The Trustees of the British Museum

There are also court paintings of couples having sex, adorned with jewelry and headdresses on lavish furniture, set against backdrops of rolling, verdant green hills and white-carved buildings.

The exhibition draws connections with Sufism, a form of Islamic mysticism that possesses similar concepts of self-obliteration through ishq, or divine, fervent love. The reverence attached to sexual imagery underscores one of the show’s most emphatic messages about Tantra: pleasure is tapped into for a higher purpose, and is not an end in itself.

At its inception, Tantra had crucial political implications. It arose during a period of civic instability in the Indian subcontinent, and thus much of its iconography features a defiant Shiva, the Hindu god who is destroyer of the universe, often depicted in Yogic poses and tinged with blue. Political leaders who drew upon Tantra were attracted to its twofold promise of material and spiritual wealth. The philosophy then spread throughout Asia by both diplomatic means and pilgrimage, as travellers returned from its eastern Indian epicentre bearing material objects – sculptures, texts, devotional items – that facilitated ideological dissemination, as Tantric schools appeared in China, Tibet, and Japan.

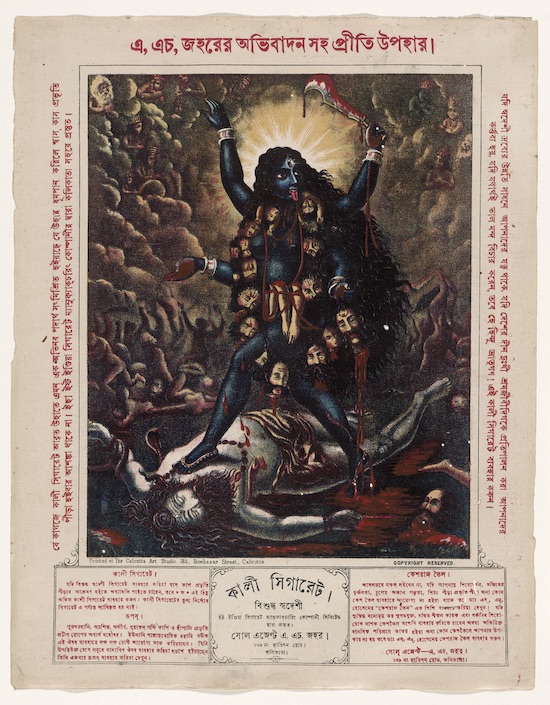

Print depicting the goddess Kali, Calcutta Art Studio, Kolkata (Bengal, India), about 1885–95. ©The Trustees of the British Museum

The iconography of Hindu goddesses makes these political connections explicit and is featured prominently throughout the show. It ranges from stone friezes of Durga slaughtering the buffalo demon Mahisha, thought to provide rulers with similar battlefield success, to more modern works, like Sutapa Biswas’s Housewives with Steak-Knives, a 1985 painting of a goddess Kali dressed in a printed tunic, her body unconventionally naturalistic. Hands raised, she carries a flower and flag print of Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes, homaging a sparse lineage of female artists. The goddess’s neck is adorned with a garland bearing the heads of dictators.

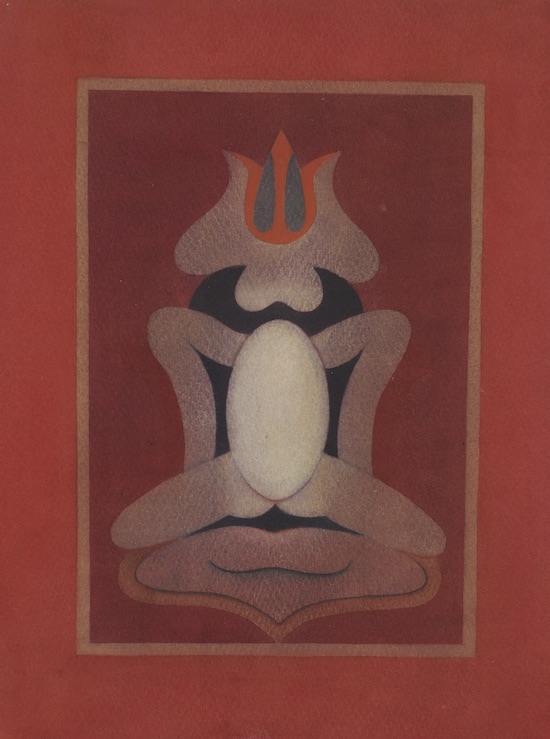

Some of the show’s highlights are Indian Neo-Tantric works like Prafulla Mohanti’s Kalika. The 1974 painting evokes the Bindu chakra, the underlying seed of creation. Electric turquoise and royal blue shroud a warm embryo of fuschia, orange, and yellow, a chromatic apotheosis. At the more figural end, paintings by the Kashmiri artist Ghulam Rasool Santosh embody the union of Shiva and Shakti, combining the transcendental nature of Tantric sexuality with a geometric reduction of form.

Untitled, Ghulam Rasool Santosh, Delhi, India, 1970s. ©The Trustees of the British Museum

Yet the show’s curation seems to suggest that due to its underlying revolutionary spirit, Tantra possesses some latent key to our contemporary period of political unrest. In the 1960s, artists and musicians did draw from Tantric philosophy through the free love movement, anti-capitalist activism, and environmentalist fervor. But the exhibition features clearly appropriative paintings by artists like Penny Slinger, who had no actual training in the divine philosophy of Tantra and were interested solely in its transgressive aesthetics, the provocative sensuality it exudes. There are several prints by Hapshash and the Coloured Coat, a multimedia outfit that created sexual imagery drawing from Tibetan Buddhist yab-yum symbology in service of psychedelic sublimation.

Reclaiming the body from shameful associations is a worthy endeavour, and the urgency of environmental and anti-capitalist activism of course should not be denied. Yet in our age of globalist neoliberalism, given an increasingly conservative, patriarchal Hindu nationalist trajectory in India (set in motion by Britain’s colonial legacy), there’s an overwhelming tone-deafness to the Museum’s assertion that “The rebellious spirit of Tantra remains ripe for the reimagining.” Perhaps it’s unsurprising for an institution that still refuses to repatriate blatant spoils of colonial plunder. But the exhibition’s underlying promotion of Tantra’s contemporary promise betrays a circular irony, fraught with its premise of redressing the philosophy’s twentieth-century orientalist misunderstanding.

Tantra: enlightenment to revolution does raise critical questions for the roles that spirituality and pleasure play in our lives, given a workday that attempts to regulate and homogenise our desires into a framework of illusory countercultural individualism. But can Tantra actually offer its uninformed Western spectant a weapon for praxis, or is it just playing into neo-imperial allure of the exotic? Steps outside the exhibition, trinkets ‘made in India,’ perfumed candles, and dyed tote bags are for sale, intimations of our answer.

Tantra: enlightenment to revolution is at the British Museum, London, until 24 January 2021