Installation View, Stephen Dobbie, Colin Nightingale, Sweet Harmony: Rave I Today, 12 July – 14 September 2019 © Justin Piperger, 2019, Image courtesy of Saatchi Gallery, London

Sweet Harmony: Rave Today starts the way many nights out once started: with a petrol station, glowing with possibilities. Getting To The Rave, an installation by Punchdrunk’s Colin Nightingale and Stephen Dobbie offers neon pumps illuminating a darkened room, messages chalked on the walls, scrawled telephone numbers, subdued sounds of passing traffic and the filtered thud of far-off beats. “Service stations were often used as meet-up points for illegal raves,” according to motorway historian Mark Goodge, “not just because they were easy to get to but because they were places where large numbers of people could easily congregate.” For Kobi Prempeh, the exhibition’s co-curator, the effect is “immersive, straight away it takes you to another world. It’s an experience.”

“What I love when I watch the audience experience it,” Prempeh continues, as we walk through the space a few weeks after the opening, “is how slowly they take themselves through here. Already we’ve pushed them into a mind-frame of: chill the fuck out and enjoy this.”

The show is divided between exhibits like Dobbie and Nightingale’s, Conrad Shawcross’s upside-down Lotus Elite, and the jittery, abstract video art of Carsten Nicolai, alongside less common gallery fare reflecting club culture’s grassroots history: flyers, photos, records, a bouncy castle. But Prempeh is adamant: “This is an art exhibition.” He’s keen to draw out the aesthetic strategies and renaissance motifs in an old club flyer or a photo of blissed-out clubbers dancing at Shoom, as he is the more obviously sculptural work on display. “We’ve done what Saatchi always do,” he says, “which is celebrate emerging artists or reposition existing artists.”

We’re standing beside a selection of photos by Dave Swindells as he says this. Swindells was night-time editor at Time Out throughout the British club boom of the late 80s/early 90s and beyond. Twenty-five years snapping London’s clubbers for the capital’s weekly listings mag, and elsewhere, working freelance for the likes of I-D, The Face, and Mixmag, in sweaty night spots from Sri Lanka to St Ives. “An absolutely iconic rave photographer,” as Prempeh puts it, “known by so many people, but never really been given a platform within which to express his artwork. We worked together with him on his selection, telling the story that way. So it’s a real celebration of different faces, orientations, and people coming together – which is what rave is all about.”

Dave Swindells, Spectrum Tent Girls (1988) Photograph © Dave Swindells, 1988, Image courtesy of Saatchi Gallery, London

The idea behind Sweet Harmony originated with Prempeh’s colleague Philly Adams, an “original raver”, as Prempeh says, as well as being the Saatchi Gallery’s Senior Director who has been with the gallery for over twenty years. “She really believed in a show which celebrated rave culture and electronic music as an art form,” Prempeh tells me. “And rave culture, specifically, as a movement which still impacts youth culture today and society at large.” But Prempeh himself is no stranger to the dance floor – even if, as he says, he “came a little bit later.” When I ask him about his early clubbing experiences, he recalls being 16 and heading to an old building in Islington in which every floor had been taken over and dedicated to a different kind of music. “It was an experience.”

“I grew up just on the border of Kent,” he continues. “It was very white. I was very often the only black person. And that night I was surrounded by people that looked like me. My own narrative began to shift just by being there on the dance floor.”

Molly Macindoe, A New Year’s Eve, Mill Mead Road, Tottenham Hale, London (1997)

Photograph © Molly Macindoe, 1997, Image courtesy of Saatchi Gallery, London

“I was also taken out by one of my older cousins to Bagley’s a couple of years later. We’d divide off – I’d go to the garage room, she’d go the house room but then I’d come and find her, and then I’d enjoy it. Or another time we’d go to The Cross, and I wasn’t so familiar with house music, but that’s where my ears began to open up.” Later on, he started DJing himself. And it was through that line of work that he first met Saatchi director, Adams.

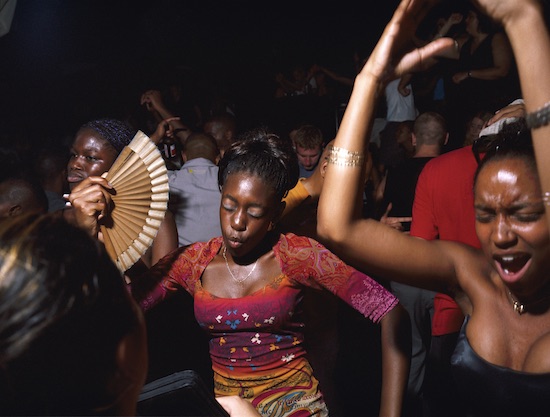

Sweet Harmony is far from the first gallery show about club culture. Just last year I visited the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, near the three-way border of Germany, France, and Switzerland, to catch a show looking at nightlife from an architectural perspective. Fabric hosted their own historical survey earlier this year, and Dundee’s V&A has a club culture show planned for September. But the Saatchi show has a broader sweep than most, drawing together work and images form the 1950s to the present day, with a wider range of subcultures and different voices. “When we were doing our research, we found the narrative was so male-driven,” Prempeh says. “What’s been great about this show is that we’ve really championed female voices.” he points, in particular, to French artist Aïda Bruyère’s project Special Gyal, recording female-only dancehall dance-offs. “What she’s celebrating here is women being empowered by using their athleticism, their muscularity, using their bodies in a free and expressive way,” he says. “I really like the fact that we could bring in a subculture that is so urban. It’s a celebration of black culture, but it’s also about how international it is.”

Ewen Spencer, Girl With Fan taken from ‘UKG’ by Ewen Spencer (2013) Photograph © Ewen Spencer, 2013 Image courtesy of Saatchi Gallery, London

Did you find that, I ask, with a lot of the artists you’ve worked with on this show, that rave was kind of a formative moment for them?

“Absolutely!” Prempeh replies immediately. “I think rave was a formative moment for our country. I do think that rave had that level of impact on our society in subtle ways that we cannot even measure. It shifted things.”

Sweet Harmony: Rave Today, curated by Kobi Prempeh and Philli Adams, is at the Saatchi Gallery, London, until 14 September