Suzanne Lacy, Anatomy Lesson #4: Swimming, 1977 (detail); five colour photographs; (C) Suzanne Lacy; Photo: Rob Blalack

"I think, in general, museums don’t attract the diversity of audiences I’m interested in," says Suzanne Lacy. "For that, I think you have to go where people are, where they live."

Anyone familiar with Suzanne Lacy’s considerable body of work over her 50-year career might express incredulity at the idea of her large-scale performance art projects, sometimes involving hundreds of people, fitting into the parameters of a ‘traditional’ career retrospective in a gallery or museum. Curators of Suzanne Lacy: We Are Here, taking place at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA) and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), were faced with a unique challenge.

Lacy’s artworks rely on installation, video and performance as part of a wider activist narrative that confronts and subverts myriad social issues including poverty, ageism, racism, immigration, gender and violence. Many of her most significant pieces involve vast numbers of participants, such as the extraordinarily affecting Silver Action at the Tate Modern in 2013, which saw her engage with more than 400 women over the age of 60, discussing their lives and the changing paradigms regarding femininity and growing old.

A similarly huge recent work is The Circle and the Square, a video installation which appeared at Sydney Biennale in 2018, showing a performance piece Shapes of Water – Sounds of Hope(2016). For this, Lacy opened up the disused Brierfield Mill in Pendle, Lancashire, as a site for former employees at the mill – of Anglo-Saxon and Pakistani origins, reflecting the area’s ethnic make-up – to return and perform shape-note singing and Sufi chanting respectively. The idea was to "reconnect individuals through the collective production of a performance." The two communities came together over music, food, and a shared history at the mill. At the Biennale, which takes place at one of Sydney’s own hubs of obsolete industry and abandoned buildings, Cockatoo Island, the work was presented as enormous video installations in an empty warehouse, the sound wrapping itself around the visitor with sublime warmth as both communities performed their a cappella singing.

Another notable recent work is De tu Puño y Letra / By Your Own Hand, which took place in Quito, Ecuador in 2014. This work involved 1500 people filling a bullring, the key performative aspect being hundreds of men reading aloud letters written by women detailing their experiences of violence.

For Suzanne Lacy: We Are Here, curators approached the problem of distilling the artist’s output into a consumable presentation by being selective about which works to include, and reproducing them in innovative ways. YBCA presents new versions of landmark works The Oakland Projects (1991-2001) and La piel de la Memoria / Skin of Memory (1999). SF MOMA presents a more diverse range of Lacy’s work, including the world premiere of the video installation of De tu Puño y Letra / By Your Own Hand, and the US debut of The Circle and the Square.

Thus, the essence of Lacy’s expansive and groundbreaking art is encapsulated across the two venues. Here she opens up about her background and ongoing practice.

As you have been considering your broad body of work and career thus far, has anything surprised you? Did any unacknowledged patterns or trends emerge?

No. I don’t often ‘consider my broad body of work’. I am much more interested in what I haven’t done, where I am going, than where I have been.

You started out aiming to be a psychiatrist and had that training. How much of your attitude to art and your aesthetic outlook do you attribute to that period of your life?

I have a degree in zoology that most evidently showed up in my early body of work, which referred in various ways to medicine and science. The Body Contract (1974) is a good example of that. Later in graduate school in psychology, before bailing from that to go to CalArts, I was interested as much in social psychology as in individual psychology. The way this shows up, probably, is in terms of my great attention to the nature of the publics produced through my work, and through my interest in social change, media, communication strategies, etc.

Many of your works have taken place outside of the United States and sometimes outside of the English-speaking world. How much have you prioritised your art taking place internationally?

I haven’t specifically prioritised it – I just go where I am invited, and where I will learn something. I like travelling and working in a place different to the one I grew up in. I am quite curious about new environments and people. Not speaking the local language is a serious problem so in a sense I don’t seek out those places and I always feel embarrassed – or humble might be a better word – about speaking English. It is something that I check out carefully with the people who invite me, and then I work with local interlocutors to ensure genuine input from residents.

You studied at CalArts in the late 1960s, obviously that’s when the counterculture was flourishing and alternative ideas were gaining traction. How much did you buy into that and how much of that era’s spirit and philosophy have you actually come to rethink and maybe reject? It seems that Allan Kaprow [a pioneer of ‘happenings’ in the 1960s and 70s] was a significant influence for you.

Early 1970s. My introduction to the California counterculture was earlier, when I was an undergraduate, and in VISTA [Volunteers in Service to America]. I suspect I was quite formulated by that moment in ways that have lasted: my relationship to my body and to physicality, my commitment to social change, equity, my lifelong interest in cross-cultural friendships, understanding difference, my general resistance to tradition. I can’t say that I’ve come to reject much of that at all.

I have, and had at the time, a different take on public issues than did Allan. He was super influential for me in terms of his challenges to the nature of art, questioning what was and was not art. I guess in a sense that was part of the de-materialism and rebellion in form. I continue to enjoy rethinking what makes something art – but for me it has more to do with the connected question: who gets to make it art, and have it seen and recognised as art?

And another thing that we used to talk about, and a way I’ve always differed from him, is that I tend to be quite comfortable with political content – content that might be thought of as meant to persuade. Allan’s work when I knew him featured round-table conversations with participants focusing on their varieties of individual interpretation.

It’s fair to say your skills go beyond what we might imperfectly call ‘art’ and a little into the realm of project management and events planning. Do you ever feel that the artistic process can get somewhat submerged by logistics in one of your artworks?

No, of course not. That seems like you might assume that art is based on inspiration, not work. Do you think that Christo’s logistics submerge his art? Or the films of Isaac Julian, wherein film crews are scheduled, and exhibition venues are arranged? Most art-making has inherent logistics of production and the application of multiple skill sets. In large-scale work, one tends to work to their expertise, and if I have a producer, one as good as or better than me, available to me, and if the project budget can afford it, I don’t need to do that and can focus on other aspects of the work.

Having said that, I do think that creation, invention and design is often more fun than production. And even more fun than that is direction, seeing the project materialise in front of me: the rhythm of directing, the intense focus, the multi-directionality of one’s attention, is quite exhilarating. After that, I’m pretty much done with the work, unless it has another new creative manifestation.

For instance, after the Quito project I thought a lot about this ongoing issue for me: how do you represent work that takes one form, like a performance, in another form, like an exhibition? And while I’ve experimented a lot over the years, in my last three projects I’ve begun to explore video installation that looks in fact quite different to the performance. So I went back to Quito to shoot 60 of the original performers in a six-channel installation. We’ll see how it works. The creative work of this new project is different to directing, but nevertheless interesting, challenging and risky. So I like doing that as well.

This idea has been mentioned before in relation to your work, but it seems to blur the lines of authorship and question the idea of the artist being on a pedestal or out of reach, and makes them accessible. One example of this might be the demythification of the artist in your Drawing Lessons (2014) with Andrea Bowers. Is it fair to say that subverting the idea of authorship is inherent in your work?

Probably. Or at least questioning authorship, trying to balance my personal desires with my ethics of representation. It probably goes back to the notion of social equity: who gets to be the artist? When I started, women and people of colour were definitely not in high evidence in the art world.

Drawing Lessons wasn’t so much about subverting authority, and more about an exchange of authorities and subverting my so-called expertise as an artist – with Andrea at the time I was her ‘boss’ in an academic setting, and her ‘elder’, but she was clearly the superior draftsman. One might read the same kind of humour in Travels with Mona (1977-8).

I thought it would be funny for me to expose my blatant inability to draw to the entire New York City art world in a Soho gallery. We shifted roles in a subsequent performance in Los Angeles, about my teaching her performance art. She was quite good at it actually, much better than I was at drawing.

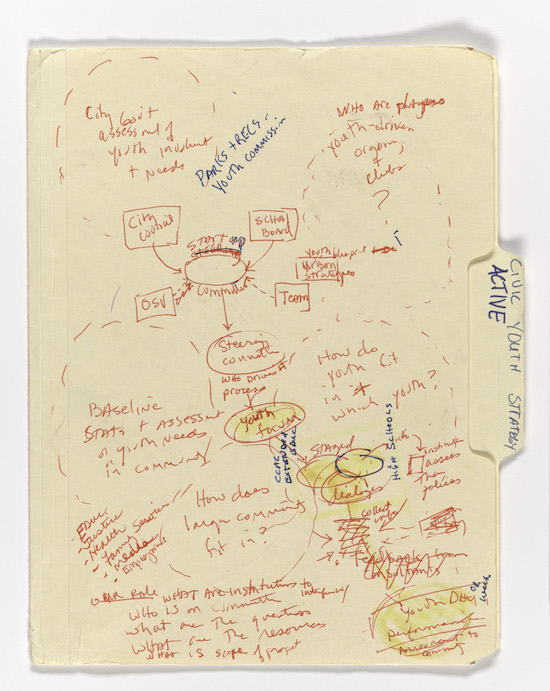

Notes by Suzanne Lacy on the ongoing civic engagement in Oakland and the Oakland Youth Policy Intiative; photo: courtesy Suzanne Lacy

Regarding The Circle and the Square that appeared at Sydney Biennale, how important to you were considerations regarding the physical scale of the project, by that I mean the size of the projections and the immersive sound on Cockatoo Island, and how the piece was such a sensory experience for the visitor?

The installation on Cockatoo was much smaller than the original installation in the same mill where we did the performance. That was such a spectacular installation site that I was kind of spoiled by the experience. I suspect that it won’t be the same in a museum, but in general the sensory and ecstatic experience of the work is the point for me. I mean it to be embodied, both to replicate the physical experience of working in a mill, and the sound of the mill itself, which was so extreme that most mill workers learned to lip read, and many had hearing injuries. Also, and this is important to the work, both forms of sound in the work are deeply embodied: the way the shape-note people move their arms, the way the Sufi chanters rock their bodies.

The work was about bringing two cultures together through music and food and identifying their common ground that way, but given some of the preoccupations of your wider body of work, how much was it also about how they share the experience of alienation and disenfranchisement as a result of global capitalism?

I don’t really see it as bringing two cultures together, though the food sharing is certainly indicative of that and was a tried and true method of bringing people together. But the food was a means to an end. What I was interested in was, as you say, disenfranchisement. The movement of people based on first, the need for labour and then the dissolution of that need that moved elsewhere.

In effect, the Pakistanis in England are an example of what we call the negative effects of global capitalism. But you can’t credit all the prejudice experienced today only to capitalism, but to the clash of cultures that happens when people retreat from the public sphere, the place where differences must be negotiated and understandings forged. That too is something that is increasingly rare in the public sphere.

And fundamentally the piece is a spiritual one. These weren’t just ‘white’ or ‘traditionally British people’ with their own music. Shape-note was not familiar to many in England, or in the region, and although some think it started there I think there is no clear agreement on that. But for me, its sonic ecstasy is matched by that of the Sufi chant, or Zikr, and people of all cultures can experience a deep commonality when you give yourself over to it without preconception and prejudice.

Suzanna Lacy with Meg Parnell, Cleaning Conditions, 2013; performances, Manchester Art Gallery as part of do it 2013, Manchester International Festival 2013 at Manchester Art Gallery (c) Suzanne Lacy; photo: Alan Seabright

What are you working on beyond the retrospective at the moment?

As soon as the retrospective is over I am excited to begin three new projects that are, in a sense, interlinked. One is in London at the Serpentine, where I will work over the course of a year to consider, with residents and staff, new ways for galleries to relate to communities.

In Moscow with V-A-C Foundation, I’ll be pursuing a similar idea based on the title of my work in Bristol with Penny Evans and Carolyn Hassan, University of Local Knowledge (2000-ongoing). In a sense it will be similar in regards to opening up an exploration of the interface between museum and public sphere in Russia.

Finally, I will be working in Manchester with the Whitworth and the Manchester Art Gallery to produce a series of ‘re-enactments’ of works that will, essentially, also be framed by the idea of the space between gallery and public. What I am excited about, but also a little intimidated by, is the opportunity to think in new ways for myself and, as usual, along with others. There is so much done already in this territory – but perhaps ‘new’ or novelty isn’t the relevant concept here?

Suzanne Lacy: We Are Here is at YBCA and SF MOMA until August 4.