Not many groups have been as unflinching about discussing their past as Suede. As well as the usual reissues and deluxe editions with which to recontexualise a career, there’s been Brett Anderson’s memoirs Coal Black Mornings and Afternoons With The Blinds Drawn, and a frank way of discussing the band’s U-shaped trajectory – vast early critical acclaim followed by commercial success, a striking decline and split, before a regrouping after time away for an increasingly well-received series of albums that culminated in 2018’s The Blue Hour.

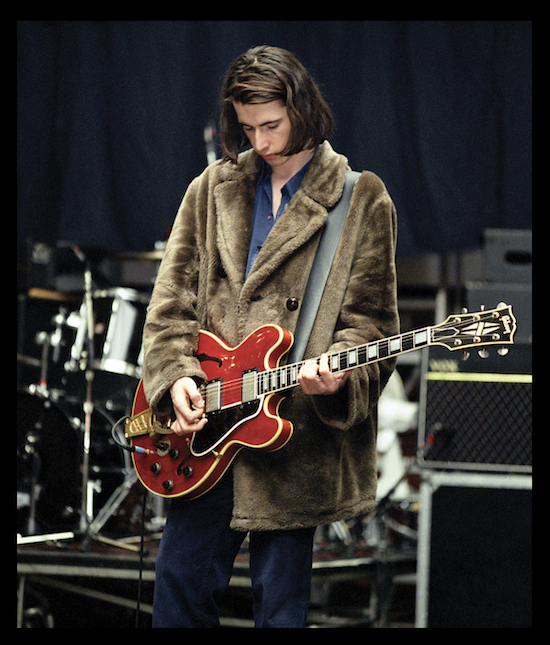

Now, drummer Simon Gilbert is on hand to add a visual element to the appraisal of this long career with his curation of new photobook Suede: So Young 1991 – 1993, a collection of images from the time of Suede’s astonishing rise. The photographs have a warm naïveté, not just in the grainy stock and washed out colours of old print processing, but the unconscious way that the band hold themselves in rehearsal, onstage, hanging out with fans and so on.

They’re accompanied by pages from Gilbert’s diaries, full of mundane references to signing on, work, paying rent, owing a few quid and then, increasingly, high profile gigs and media appearances. His photo captions are wry and witty, delving into his excitement at the time, interaction with characters who would appear at gigs with cases loaded with all kinds of rare herbs and prescribed chemicals. Like Suede’s singer, he’s critical too, most notably of the Love & Poison film that showed the band at the height of their early pomp.

Gilbert got stuck in the UK in March 2020 when he came over for a week to work on the next Suede album. Covid descended and he’s subsequently been stuck on the other side of the world from his home "in the middle of a rice field" in rural Thailand, where there are cobras in the garden and buffalos wandering past. Speaking via FaceTime from an attic room somewhere in the English Midlands, Gilbert says that he’s itching to get back: "it’s very, very different – I thought London was a shithole before," he says, somewhat at odds with the Suede mystique of valorising the English capital, "I’m afraid it is, long gone is romanticising about the streets of London – fuck that!"

Part of Gilbert’s motivation for bringing out Suede: So Young 1991 – 1993 is not knowing what to do with the giant archive of Suede ephemera he’s collected over the decades, a collecting habit that began in his punk rock loving youth. He can’t really ship the boxes of material out to Thailand, where it’d be at risk from the damp and humidity in his rural hideaway, and currently t-shirts, editions of records, Suede’s 1993 Mercury Music Prize statuette all sits in boxes in the loft where he’s been riding out the past 18 months of chaos.

He’s even got old clothes – the shirt he wore on the band’s first Top of the Pops appearance, and the black leather jackets that the band wore in the photo shoot for 1996 record Coming Up. A planned exhibition to go with the book launch is on ice, again thanks to covid, but for now Suede: So Young 1991 – 1993 is a lovely little number that, far from mythologising the group, gives a charming glimpse behind the scenes of the rise of one of our finest guitar pop groups. It’s Suede at their best, finding the extraordinary within the ordinary, romance in the tedious, knowing that living happens best in the sweat and smoke.

What I like about the diaries is how minimal they are, there’s no retrospective aggrandisement – it’s all pleasingly functional, even in this mad week where you quit your job, sign on, and then do the Melody Maker cover

Simon Gilbert: The diary was a functional thing, we were rehearsing everyday so there was always something to write in, ‘what the hell’s going on tomorrow?’ I was so busy. Me and Matt weren’t on the dole for that long, we worked right up until we got signed by Nude, I’ve never been one for being on the dole, I’ve always liked to work. I was in the box office at ULU, It was a great job and I loved it, I used to sit around selling tickets, smoking fags and chatting to people. I was reluctant to give it up in the hope that we might become famous, but within a couple of weeks of signing on we were on the front cover of Melody Maker, it was bizarre. The whole of life changed from that one picture, into the stratosphere from then on. I haven’t got a great memory to be honest, and I think without those diaries the whole experience would have been a different view on it. To have what actually happened is great and it keeps my memory fresh.

Did the diary help write the captions for the book?

SG: Exactly, I just wanted to put a few little bits here and there just to tie in with the diary pages. Looking at the page where it says ‘Top of the Pops Dot Cotton’ I remember clear as day going to the canteen and sitting down, Dot Cotton was there, Ian Beale was there, Brett was there and Bernard was there. it was was the most bizarre thing – I took it out of the book but I did a bit of acid the first time we did Top of the Pops, I was sitting next to Dot Cotton tripping, it was quite weird.

Drugs appear quite frequently in diary entries

SG: I thought I’m not going to edit the diaries at all. You can see as the book goes on there are little Cs in a circle or A in a circle, I don’t know why but I started to document my drug taking. Looking back it’s ridiculous, ’94 it’s basically every day, the amount of fucking money! I think I did it to keep an eye on how much I was spending on naughty things like that and it’s frightening, let me tell you.

One of the really lovely aspects to the book is the frequent appearance of fans, not just waving adoringly at the band but hanging out with you all

SG: Fans have always been a big part of Suede. I think you’re either a band that hangs out with the fans or you’re a band who’s aloof and you don’t, and right from the beginning we were hanging out with fans. After every gig if there wasn’t an aftershow with 30 fans backstage it wouldn’t have been a true gig. The fans are still so dedicated. Back then there wasn’t the internet so I’d have to sit and write a hundred replies to fans every week, I loved doing it and I quite miss it, writing a letter. In the book there’s a little bit about this run of three gigs in Southampton and a few other places, when suddenly there was this fanclub and fans there. Before it was gigs of people with crossed arms, but those were the three gigs where it really took off and it just got bigger and bigger.

SG: If you see pictures of a run of gigs in our early touring days we’re all wearing the same clothes. Our touring clothes were literally all in a plastic bag, so the van used to stink of sweaty clothes that we’d played in the night before. We all lived in shitty houses, we didn’t have any money. Nobody sat down and said ‘let’s create this image of wearing flamboyant 70s clothes’, it just happened really, it naturally became this different band to everybody else. We never used to hang around with other bands, we weren’t on the scene. There’s this big myth of this Britpop thing that all the bands used to hang around in Camden, it was just so far from the truth. I don’t think I’ve ever been to the Good Mixer. I don’t know why we looked so different, but we did.

How was it for you and Matt playing in musical dialogue behind this singer who puts on a performance and a brilliant guitarist, these flamboyant people in front of you?

SG: I’ve always been one for sitting back and watching the show. Apart from Keith Moon, there’s nothing worse than when you go and see a band and you’re watching the drummer and thinking ‘oh calm down’. There’s a place for everyone and everything in its place, and a bass player and a drummer sit at the back and they keep the fucking show going. The flamboyancy thing about Suede is a bit of a myth as well. People see us as this flouncy thing because they saw Top of the Pops or they saw the Brits at Ally Pally, but at the actual shows Brett wasn’t flouncing around onstage, it was pure fucking energy and punk. So I don’t think they were that flamboyant to be honest.

That’s interesting, I only saw Suede live for the first time on the Coming Up tour, which was a lot more stomping, swaggering and punk rock, not flamboyant at all. My experience of that early Suede is shaped entirely by retrospectively watching Top of the Pops, the Brit Awards and the Love & Poison Brixton film.

SG: I tell you why the Brixton video didn’t do it for me, and it’s because it didn’t capture what Suede were about, that’s why it was so crap. We’d not done TV at all, and as soon as there’s a camera on you, I used to act completely different. I hated that I knew someone was filming what I was doing and I couldn’t relax or act naturally at all. There’s one from Manchester Boardwalk which is almost like a Suede show but there were telly cameras on the stage so it wasn’t like a proper, in-your-face Suede show. I don’t think any TV show or anything like that has ever captured early Suede how they really were.

It’s fascinating how in that pre-internet air the perception of a band is entirely shaped by two or three appearances or films.

SG: Absolutely. Someone asked me the other day, ‘do you think releasing this book destroys the myth about being in a rock band’, and I said well the internet has destroyed the myths anyway.

The book is also really good at the backstage stuff, hanging out with fans or the less pleasant things – there’s the amazing photograph of Brett looking sick as a pike.

SG: He’ll probably hate me for putting that photo in. Touring wasn’t mundane at that time, all of us had been striving to do this for so many years, so to actually do it – there’s nothing mundane about sitting in a van, covered in beer for 19 hours going to Dublin, there’s nothing mundane, it’s fucking great, it’s fucking brilliant, amazing, so you lap it up – doesn’t matter we didn’t have any sleep last night, doesn’t matter, we’ll play a gig, so eventually you’re going to get fucked and that’s what happened on that tour. It was the first gig we’d ever cancelled and it was dreadful – we had to stay at a Bradford Novotel while Brett recovered. That was mundane, the most depressing thing ever and I remember it clear as day. A horrible, horrible Bradford Novotel with those white plastic chairs where you sit on them and they sort of bend. But there was nothing mundane at all about early touring, you’re that sort of age, you’re playing a gig, everything’s paid for and you get paid for it – fantastic.

Did that feeling persist for a long time – did you feel like you lost it, then got it back more recently?

It lasted a long time, right up until halfway through the Head Music tour and then it did become mundane, in the music we were producing after that, as you know A New Morning is not spoken about in the Suede camp as very good. It was playing the same venues, the same shows, everything had become mundane, hence we split up for seven years. I think having had that seven years we came back feeling ‘come on, let’s do it again’, with that original attitude, and that’s still going on now, especially with the new record as it’s all back to basics with the band playing in a room. We did lose it, but as Brett said, he got his demon back, and Suede got our demon back as well.

So Young: Suede 1991 – 1993 is out now, for more information go here. Suede are on tour this autumn, for tickets and dates please visit the band’s website