“The Real Art of Street Art,” was what the little strip of paper promised me. I didn’t think much of it at the time, but later the phrase returned to me and began to stick in the craw. The Real art?

There were about a half dozen of them, tucked haphazardly into the lower rim of the frame housing the bus map and timetable at the stop just round the corner from me in North London. From a distance they looked more like they should be advertising a massage parlour or babysitting service or one of those spiritual healers that promise to cure you of sexual impotency, black magic curses, and all outstanding debts. Certainly not, as it turned out to be, some sort of online exhibition of photographed graffiti.

Art historians are used to the distinction between art and non-art – a line, history tells us, that we may attempt to police at our peril. Less familiar is the line supposed by our flyer here between art and real art, or between “real art” and… what exactly? Some other sort of art, somehow less real, and therefore more artificial. An art overburdened with artifice. Real art vs. art-plus! Is this little square of paper suggesting that street art is real art because it has less art in it?

Last week the Russian agit-punk band Pussy Riot released a new video for their song ‘Refugees In’. It depicts the group performing inside some sort of cage while, outside, protestors clash with riot cops in a surreal carnivalesque environment. It was shot entirely at Dismaland, the dystopian theme park created by the anonymous street artist Banksy whose works now regularly fetch well over a hundred thousand pounds.

Pussy Riot’s request for filming permits must have appealed to the custodians of Dismaland. Their recent prison sentence has lent the group what money can buy only with difficulty: authenticity. But theirs is a curious, almost paradoxical, sort of authenticity. The semiotics of the group have always played with the codes of pop. With their signature day-glo balaclavas they resemble Warhol screenprints of twentieth century guerillas. Their music, too – at least on the evidence of this latest clip – sounds increasingly close to the sound of commercial pop. They are even able to stage their own imprisonment, in the midst of a fictional scenario, in one of their pop videos. To pick up again the word we learnt at Frieze a few weeks back, pop authenticity might be the “paradessence” of Pussy Riot.

In Alex Shakar’s novel The Savage Girl, the trend spotter, Chas, explains to the main character, Ursula, that consumer motivation is all about this thing he calls paradessence. “Every product has this paradoxical essence,” he says as they wander through a supermarket. “Two opposing desires that it can promise to satisfy simultaneously. The job of a marketeer is to cultivate this schismatic core, this broken soul, at the centre of every product.”

Banksy, too, has his paradessence, which overlaps with Pussy Riot’s: cynical authenticity. With his outlaw-like anonymity, he trades on the authentic allure of the real, even as his work drips irony towards every sort of truth claim.

When I lived in Paris a few years ago, there seemed to be an awful lot of gallery exhibitions of street art, or at least street art style art. Someone asked me, at the opening of one such show at Agnès B.’s gallery in the Marais, what I thought of the work. “I like street art in the street,” I said. At the time, all these brightly sprayed swirls hung up in their neat frames looked a little like caged parrots to me.

On reflection, I’m not so sure what my problem was. Keith Haring, Basquiat, and so on, was a long time ago, after all. Why try and police such things? Kids are getting paid then I’m happy for them, I suppose. It does still feel a bit odd that “street art”, even when transposed onto canvas and gallery walls, remains such a recognisable style though. Why is that?

Around the same time, the Palais de Tokyo had opened up their basement to graffiti artists, Lek and Sowat. It was a cavernous space that looked less developed than unearthed. Being show around it on the press preview night, two things struck me about the project: the first was the way the artists themselves seemed to being exhibited alongside their work – exotic specimens from the banlieues! The other was the cosmology implied by show’s subterranean location. Afterwards, canapés and white wine were served to the invited guests on the art centre’s very top floor.

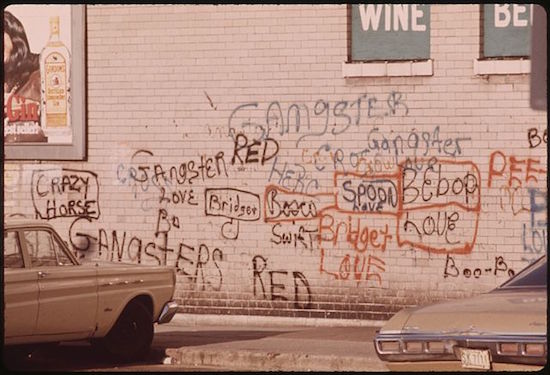

Back in London I seem to see far fewer exhibitions advertised promising street art – until that flyer at the bus stop the other day. But I do quite regularly walk pas a stretch of wall on Sclater Street, between Brick Lane and Shoreditch High Street Overground station. This stretch of wall is like a gallery in itself, with the most rapid turnover of exhibition programmes known to man. Scarcely has one artist stopped than another is already stepping up to recover the still drying paint of their predecessor.

It would strike me as a terrific amount of time and effort for such fleeting effect, but then I thought about how many people I had seen pausing to take pictures of the display on their phone. Many of the tags now used by street artists, already quite close to corporate logos in some respects, have begun to take on the marks of internet awareness: they are prefixed by hashtags or @ signs, sometimes containing full URLs. The net offers a second life to their work. But the transience is part of what makes it attractive to snappers in the first place. Ephemeral permanence might be its paradessence.

After the contents of one’s dinner plate, graffiti might be the biggest cliché of online photography. Search for it on google images and you’ll be able to keep scrolling for a long time. I suspect it probably has less to do with the now hackneyed metaphor of the web as a “virtual street” and more to do with the simple fact that it is eye-catching, and snapping it and posting it is now so easy that thought and quality control needn’t ever intercede in the process. It is interesting the different kind of hits you get if you search “street art” instead. Most of the latter look like Banksys.

Two different court judgements from the last five years show that Banksy’s name has become synonymous – in the eyes of the law at least – with “real” street art. In 2011, a London prosecutor summed up his case before the bench by damning his subject as “no Banksy”. He got 27 months. While in December 2013, a Manchester magistrate let off his defendant, describing him as “the next Banksy”.

In general, I tend to prefer my photographs of buildings to be unadorned, but I shan’t complain, as David Lynch recently did, that it has “ruined the world.” I do, however, think there might be cause for concern when the line between art and non-art – or “real” art, for that matter – is one that can be policed in the court room.