Lucio Fontana, Io sono un santo, 1958. Ink on paper on canvas with cuts, 50 x 65 cm © Fondazione Lucio Fontana, by SIAE 202i

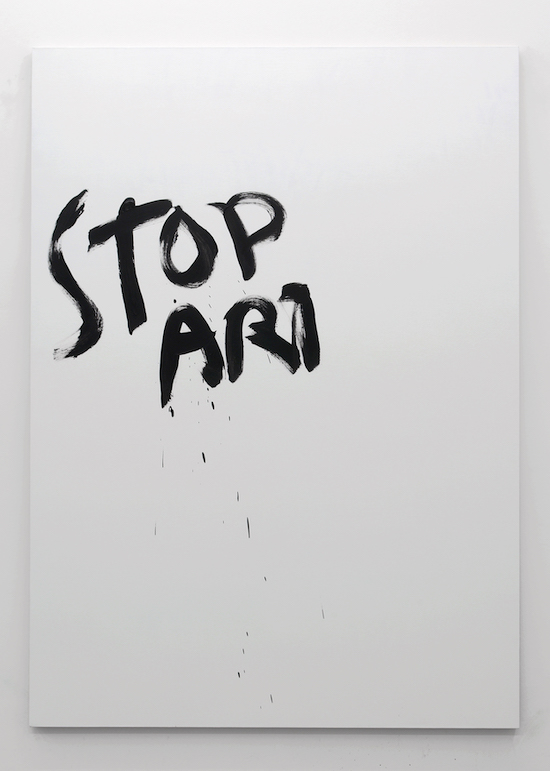

With its image of a gloved hand poised with a dagger, bathed in a sickly yellow light, the poster for Stop Painting looks like a scene from some 70s giallo picture. But the hand of the murderer here does not belong to Dario Argento but to artist Lucio Fontana, and the victim is not a glamorous young woman but a stretched canvas – or, you might say, it is the art of painting itself. Curated by Peter Fischli for the Fondazione Prade in Venice, Stop Painting is an expansive tour through the many deaths of painting, the many different means by which painting’s demise has been heralded, beckoned, lamented, and celebrated from within painting itself. In a way, it is less an exhibition, than a wake.

First exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1831, Paul Delaroche’s oil on canvas, Cromwell and Charles I, is a curiously sombre work. Based on a fiction told by Chateaubriand in which the triumphant Roundhead cannot resist opening the coffin of the dead king, here Cromwell looks anything but exultant. With his face ashen and eyes downcast, he looks almost nostalgic, even rueful. Delaroche strenuously denied the painting was intended as a comment on France’s own then recent revolution, but it was certainly perceived to be by many at the time. A little short of a decade later, Delaroche would have cause to grieve himself. Seeing the first Daguerreotypes in 1939, he is said to have claimed, “From today, painting is dead.” If the quotation is real (there appears to be some doubt), Delaroche himself was in part responsible for that death, as the man tasked by Francois Arago to produce a report on the artistic validity of the new medium – a report which led in turn to the French government opting to finance Daguerre’s experiments. Like Cromwell, art seems to have been in a state of mourning ever since.

Over a century later, Walter De Maria would allude to painting’s strange zombie-like persistence with his early work, Silver Portrait of Dorian Gray. Originally made, according to an inscription on the work’s reverse, in November 1965 for the collector Robert Scull, the piece consists of a square forty-inch silver plate framed by a velvet curtain which may be drawn or parted as wished. Like Louis Daguerre’s early photographic apparatus, De Maria’s silver was polished up like a mirror and treated to make it light sensitive – as the inscription continues, the work “turns colour as the air touches it.” I don’t know if Scull ever managed to successfully ‘photograph’ himself with De Maria’s work, but today the Silver Portrait shows nothing more than a dull grey surface, making it one of a number of uncanny voids and erasures spread across the Fondazione Prada.

Halfway up the stairwell, for instance, you could be forgiven for missing Lawrence Weiner’s (1968) work, A 36” by 36” Removal To The Lathing Or Support Wall Of Plaster Or Wallboard From A Wall (I did, at first). A kind of anti-landscape to match De Maria’s anti-portrait, this thirty-six inch square slice into the plaster of the Prada Foundation’s eighteenth-century Venetian palace reveals a patch of brickwork in many ways as detailed and complexly textured as any Jackson Pollock. But perhaps modern art’s most famous erasure has been rather cheekily un-erased. Back in 1953, Robert Rauschenberg spent ages painstakingly rubbing out a drawing that Willem De Kooning had, somewhat doubtfully, donated for the task. Then, in 2010, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art went and produced a digitally enhanced infrared scan of Rauschenberg’s work. The results, exhibited here at the show in Venice, reveal a spidery network of lines and shaded areas. SFMoMA’s website notes, “De Kooning himself used erasers as part of his drawing process, so it is possible that some of the lines revealed by this image were erased by him before the drawing entered Rauschenberg’s hands.” Perhaps some form of erasure has always been inherent in and inseparable from the art-making process from the very beginning.

Merlin Carpenter, The Opening: Intrinsic Value: 5, 2009. Oil on linen, 213.5 x 152.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and the Simon Lee Gallery. Copyright of the artist

Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Vetrina (Ogetti in Meno) recalls King Charles’s coffin: the Italian artist has placed his spattered boots and painting overalls upright inside a man-sized cuboid vitrine, as if he himself had been recently erased. Like Jean-Frédéric Schnyder’s Hudel, exhibited just beside it, Vetrina reveals a fascination for painting’s remains – or with the remainder as, itself, a kind of painting. Schnyder’s vast work, almost filling the room on its own, consists of a kind of abstract expressionist patchwork quilt sewn from all the old rags the artist used to wipe the paint from his used brushes over twenty years. It’s sheer expanse testifies to the work as labour, whilst simultaneously gesturing towards its absence. Schnyder’s rags – and Pistoletto’s overalls – might usually be considered no more than an incidental supplement to the act of art-making, but presented as works they seem to question – following Jacques Derrida’s gnomic comment in Of Grammatology – exactly what is implied by this logic of supplementarity.

De Maria’s Portrait is not alone here in alluding to or allowing for the veiling of a work of art. In the late 2000s, Klara Lidén gathered old advertising posters in the streets and stuck them together, one on top of the other, before finally laying an equally-sized sheet of white paper over the whole pile, covering up whatever messages were once present. Similarly, David Hammons’ Untitled (2008) drapes a torn sheet of blue tarp over his painting, occluding its surface except via a few small tears here and there through which a glimpse of the underlying canvas peaks through. But perhaps no-one has grasped the erotic power of this process of veiling better than Albert Oehlen and Martin Kippenberger who, in 1982, encases a stack of paintings in a closed brown box and called it an Orgonkiste after Wilhelm Reich’s orgone energy accumulators, putative generators of orgiastic potency.

If Oehlen and Kippernberger’s box full of canvases resembles a coffin for painting, it is already anticipated by a cartoon shown here from the Exposition Universelle of 1855. Honoré Daumier’s satirical print, first published in Le Charivari, depicts two pallbearers carrying away a stretcher full of canvases, all marked “refusé”. We will always, it seems, be late for the end of painting. But to quote Derrida once more, it is only from the possibility of its death that art can be interrogated. As Fischli himself concludes in his introduction to the exhibition booklet, after the end of painting, then “painting appears illuminated, re-auratised.”

Stop Painting, curated by Peter Fischli, is at the Fondazione Prada, Venice, until 21 November 2021