The Tate Modern makes a valiant attempt to transmit the energy of nearly two decades of radical black art in its new show, Soul of A Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power. But it’s the corresponding Soul Jazz compilation that better captures the defining struggle and strife in Black America during the Sixties and Seventies.

Given its unwieldy scope the Tate Modern show was always going to fail. Instead of delivering a cohesive visual spectacle it’s all over the place, with wild sculptures clashing with equally vibrant paintings, as each one of the different groups in major American cities battled to best represent the growing confidence and stridency in Black artists.

There’s a genuine delight in these displays from the best of the fractured African American arts scene, dating from the height of the civil rights movement to the early days of rap. And despite the noise the exhibition delivers a fascinating look at some compelling American visual artists who shared oppression as their common creative narrative. This revolution would be displayed.

Take the collages of Romare Bearden. His 1964 work Pittsburgh Memory opens the show with two inquisitive faces craning in, their merged mugs peering straight at you. The precision of these cubist faces means business, while the anarchic energy of the ripped paper is all attitude. Immediately you’re on the defensive and it’s clear you’re on their turf.

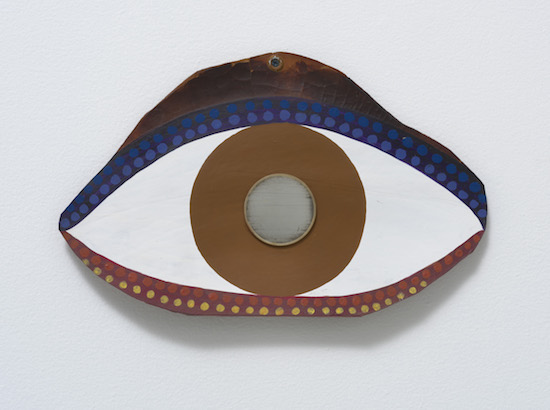

Meanwhile, the singular stark beauty of Elizabeth Catlett’s elegant carved mahogany fist Black Unity (1968) and the mystical optimism of Betye Saar’s Eye (1972) exude a sophisticated and calm voice, despite their radical imagery. Their mission was summed up well by fellow artist David Hammons in 1969 when he wrote: “I feel it is my moral obligation as a black artist to try to geographically document what I feel socially.”

To explore this obligation the exhibition zigzags across 200 works by 60 artists while the artists pose fundamental questions about their country, their souls and their art. Is there such thing as a ‘Black aesthetic’? Does it even matter? What was it about this era in American history that makes its art so pulsating?

Noah Purifoy’s incendiary Watts Riot (1966) offers perhaps the best reply. Assembled from the haunting, charred remains of the city of Los Angeles after six days of unrest, the ghostly stencilled letters on a piece of its detritus bear all the technical fine-art hallmarks of a work by Robert Rauschenberg or Jasper Johns.

But what separates it from the art of his white peers is the red-hot anger of a city which had just erupted into a cauldron of racial hate. Stemming from an ugly confrontation between a black motorist and a white police officer on a hot August day in 1965, the black population’s rebellion resulted in 3,438 arrests, 1,032 injuries, 34 deaths and more than $40million of damaged property.

The shifting hues of Purifoy’s charred bits and their prosaic arrangement quietly defies their chaotic genesis. While the blackened depths of the burnt textured wood offer an infinite visual portal to both the past and the future, it also reflects the historical stridency of the Dada artists in early 20th century Europe. And in terms of political unrest it’s impossible to ignore Purifoy’s foreshadowing to the riots that erupted in 1992 after the group of LA police officers who beat motorist Rodney King were acquitted.

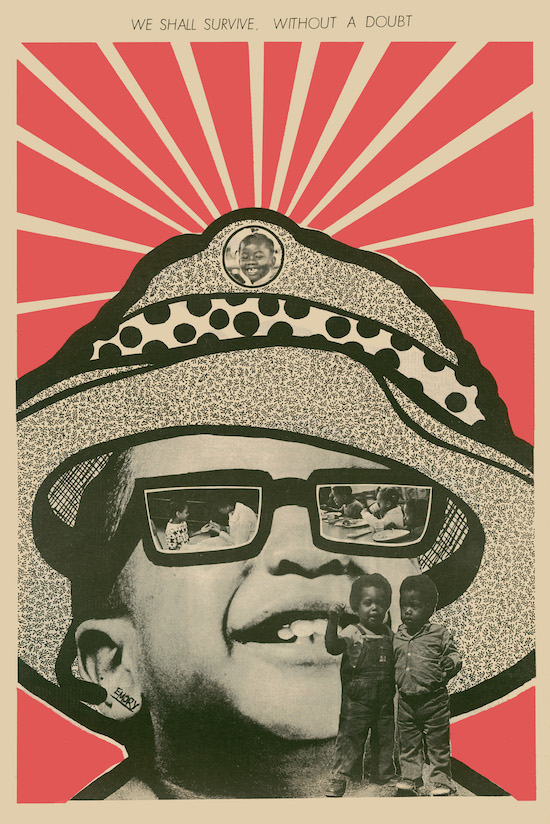

After Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s March on Washington in 1963 black artists across America began to organise and form collectives. From the Spiral Group, OBAC, The Black Panther Party and Emory Douglas’s shocktastic and stark newspaper designs, to the literary designs of Amiri Baraka and his attempts to define the aims of the Black Arts Movement, AfriCOBRA and Kamoinge, the artists sprawled from Boston to Oakland, Chicago to Washington DC, with a shared artistic voice rejecting the country’s ugly and endemic racism. Yet their art is difficult to describe as the ‘soul of a nation’. It was more like the conscience of a nation, refusing to be regarded as anything but equal.

Their artistic responses – and the subversive revenge – is everywhere to see. But the story is only partially told through the eyes. One of the integral missing pieces of the African American cultural experience is conveyed through the ears. Music is ever-present in the exhibition, with Roy DeCarava’s black and white portraits of jazz luminaries such as John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Elvin Jones looming large, while Jeff Donaldson’s rough-hewn 1967 impressionistic sketch of Miles Davis still seems so fresh. Donaldson himself asked: “Do you consider yourself a black visual artist, an American visual artist, or an artist, period?”

The musical dimension is the jumping-off point of the better-focused accompaniment to the show from London’s independent Soul Jazz Records. The label has issued its own compilation, Afro-Centric Visions in the Age of Black Power – Underground Jazz, Street Funk and the Roots of Rap 1968-79. In parallel with the show it uses the superb Barkley L Hendricks 1969 painting entitled Icon for My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved Any Black People – Bobby Searle) as its central image.

This superb compilation presents a much more concentrated look at the new African American-led revolution in sonics during the era. Opening, predictably enough, with Gil Scott-Heron’s legendary proto-rap tune ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’, it’s the killer Roy Ayers Ubiquity track ‘Red, Black and Green’ that truly gets the blood pumping.

The fearless Soul Jazz release marks this ‘intense period’ of musical creativity when jazz musicians created ‘new music that combined a number of political and musical qualities’ as the moment where African musical sensibilities of call and response, improvisation, polyrhythms, swing and syncopation were adopted in a race to create a new sound.

These threads are beautifully tied up in early Sun Ra Arkestra trumpeter Philip Cohran’s live suite and tribute to Malcolm X as it snakes through a propulsive battery of drums and horns before powerfully chanted lines kick in: “White man is our enemy/ Who perfected slavery/ Look what they have made of me/ Fools without a memory/ Always talkin’ brotherhood/ White man you just ain’t no good/ Now we have you understood/Malcolm X is kindlin’ wood.” It’s an intense meditation on the slain civil rights leader and features some profound licks from Cohran for good measure.

Not to be outdone, trombonist Phil Ranelin lays down a sultry funk on ‘Vibe From the Tribe’. It’s one of the many hard-to-find tracks included and it’s remarkable due to the unique furrow it ploughs between far-out jazz and its killer rare groove beat.

And following on, Joe Henderon’s jaw-dropping Black Narcissus sees the tenor saxophone explore his huge range of tone and emotion with the likes of fellow giants Herbie Hancock (electric piano), Ron Carter (bass), Jack DeJohnette (drums) and Mike Lawrence (trumpet). Taken from his Power to the People album from the Milestone label in 1969, it perhaps survives the passage of time better than any of the other tunes.

If nothing else, this musical accompaniment to the Tate Modern show lets you revel in the swagger and power of the moment. As many of these jazz figures were operating outside the musical mainstream, it allowed them to explore their new-found African influences and be uncompromising in their political themes that fed straight through to Marvin Gaye, Miles Davis and the burgeoning rap scene of the early Eighties.

By the time you reach the 1976 photograph by Dawoud Bey titled A Boy in Front of the Loews 125th Street Movie Theater at the Tate Modern this cultural confidence and swagger is reaching its zenith. It’s neatly summed up in the boy’s pose as well as artist Frank Bowling’s reflection: “We mustn’t lose sight of the fact that in a sense black art, like any other art, is a posture.”

It’s clear that the Tate Modern knew it was facing a near-impossible task in creating the show. Even the museum readily admits its haphazard attempt by offering this frank acknowledgment: “We hope it contributes to the impetus for yet more focused exhibitions in the future.”

They may have been late to the party, but the museum deserves credit for putting its money where its mouth is. It’s invested heavily over the past few years by adding works by Bearden, Hendricks, Norman Lewis, Jack Whitten, Sam Gilliam, Frank Bowling, Lorraine O’Grady and Senga Nengudi to its collection. This proves that the discussion of art, politics and race in American history still provides a uniquely fascinating look and listen.

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power continues at Tate Modern until October 22. Soul of a Nation: Afro-Centric Visions in the Age of Black Power is out now on Soul Jazz Records