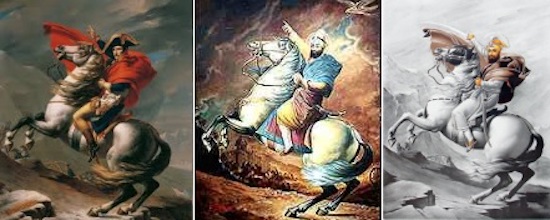

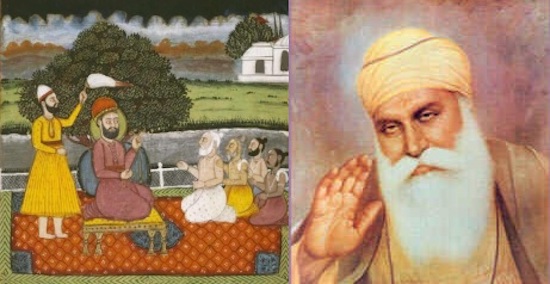

David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps; Gurbux Singh’s Guru Gobind Singh; A poster based on Gurbux Singh’s painting, with added sword in hand

A hand points over the mountains to Italy, or Kashmir; a man who is the French Emperor, or a Guru, urges us to follow.

David’s painting of Napoleon can look ridiculous to us – the lead-guitarist mid-solo – but that’s because it was painted as propaganda, not as a true likeness. When Gurbux Singh painted Guru Gobind Singh a century and half later, he used David’s Napoleon as a model to convey a different set of ideas; ideas which have refracted into completely different meanings.

It is only one exchange in a long history, speaking to the heart of contemporary debates about ownership and cultural appropriation.

Bari Weiss recently penned a piece for The New York Times titled ‘Three Cheers for Cultural Appropriation’, in which she argued “that everything great and iconic … comes when seemingly disparate parts are blended in revelatory ways”. She went on to criticise “the strident left” who want to ruin the party.

There have been no shortage of rebuttals. I would like to discuss the “revelatory” element Weiss alludes to. While I agree that cultures can interact in surprising ways, the fact of this interaction doesn’t render appropriation benign, but nor does it make every act of appropriation ‘wrong’. I want to talk about yogic paintings to explore the idea that cultures and their interactions are more complex than this debate often allows.

Yogi Bhajan found fame in New Mexico, far from his native Punjab. Born Harbhajan Singh Khalsa in 1929, and raised in a traditional Sikh home, he emigrated to the US in the late 60s, and founded the 3HO (Healthy, Happy, Holy Organization) in Espanola. It dedicated itself to “uplifting and inspiring” people through Kundalini Yoga, meditation and Bhajan’s own “philosophy”.

The ostensible author of over 30 books including yoga manuals, cookbooks, and even a treatise on masculinity, Bhajan shaped Kundalini Yoga the world over. The organisation is listed as a cult by several watchdogs.

Both Bhajan’s philosophy and Kundalini Yoga are syncretic. The philosophy emphasises living well using Sikh and Hindu vocabulary, Christian analogies, claiming chants can channel and align spiritual realities. Kundalini Yoga focuses on awakening latent – typically female – energies within human beings; it became a specific practice only when Yogic ideas were transplanted to the West.

Although Bhajan and the 3HO are eschewed – and sometimes excoriated – by Sikhs, Bhajan was the Guru to his followers. The organisation established its ashram in New Mexico, where a local painter, Ed O’Brien, inspired by the Yogi, painted the following fresco.

Ed O’Brien’s fresco in Espanola for the 3HO ashram, all credits Ed O’Brien and 3HO

On one side sits the cross-legged Yogi Bhajan as a young man; opposite him is the ‘future, ideal Sikh’. In between is Mary, standing inside a Khanda, the symbol of Sikhism. Flanking her are portraits of Sikh Gurus, illustrated with scenes from their lives. Astral lines intersect with the third eyes of the sitters. Bhajan frequently preached in front of the fresco.

To Sikhs and Christians, such an image might seem offensive and even sacrilegious. But it actually reveals a long-history of encounters between the East and West.

Who are the Sikh Gurus in the Espanola painting?

Verifiable historical information about the man, Nanak is not abundant. Instead, we rely on fragments, parables, folk-tales. He was a Guru, who dressed like a faqir, or a farmer. He had a round face, or a lean one. A large body, or a wiry one. His beard was long and flowing, or short.

Ultimately it does not matter, as he, the founder of Sikhism, wrote: "Through the Guru’s Teachings, the Light shines forth."

Guruship is an essence, not a form. The teaching, its meaning and authority are the important things, rendering the Guru’s appearance irrelevant.

Born CA 1459 in what is now Pakistan, Guru Nanak taught that the Guru is a guide to the divine, but not an intermediary between God and humanity. Nor is the Guru a God. Guruship was held by 10 men between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, with authority passing from one to the next. Since the death of the final human Guru, Guruship has been held by one written-text called the ‘Guru Granth Sahib’, with each physical copy revered as the living Guru.

Although Sikhs reject idolatry, images of Gurus abound. They adorn homes and temples, even Bolloywood production companies. This, despite no painting ever being made of a Sikh Guru during their lifetimes, and no reliable evidence describing their appearances. Therefore, paintings of Gurus are imagined.

So how did they come into existence?

Early Sikh art begins in the sixteenth century on the periphery of handprinted books; interlacing illuminations for the emerging religious community. Paintings of Sikh Gurus appear roughly a century later. And since Sikhism only began rigorous systematisation of its beliefs into a ‘mainstream’ religion in the nineteenth century, the disunified Sikh groups each imagined the Gurus differently.

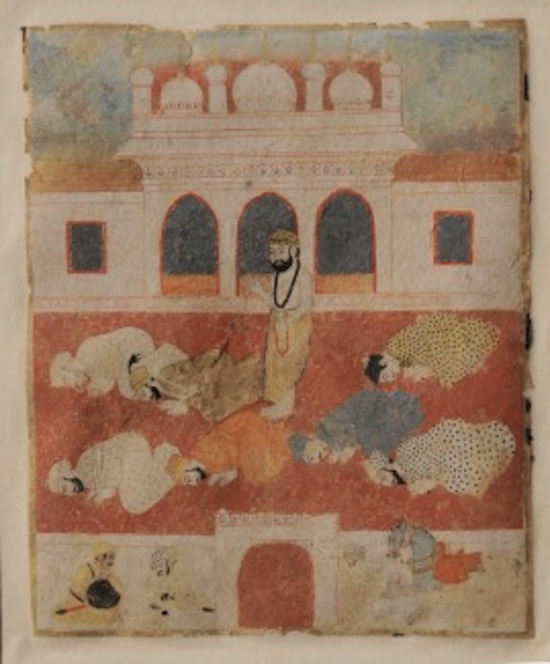

Sikh artists took prevailing Mughal and Hindu court styles, transforming them into their own. They painted Gurus using watercolours on paper, employing multi-layered scenes, often without single-point perspective. Figures were rendered in two dimensions, and were almost always in action. These were almost always produced for Sikh elites. Take this image of Guru Nanak Dev, painted around 1825.

Guru Nanak Dev standing in the midst of devotees, unknown Sikh School artist, CA 1825, Google Cultural Institute

Although Sikhs do not treat images of Gurus as historically reliable, paintings play an important social role in binding Sikh communities together. However, the paintings of Sikh Gurus people produce today are no longer in this style, nor in a style ‘native’ to Sikh culture. Indeed, the structure, scheme and composition of contemporary Sikh paintings is taken from Western art – as are the materials that produce them. These latter paintings are the ones which would go on to influence Kundalini artists in the West.

The Sikh religion has almost always been enclosed by empire: The Mughals, the British, and for a time between, the Sikh themselves. The brief decades of Sikh Rule in the early nineteenth century facilitated artistic patronage, during which time, the ‘Sikh School’ flourished. Sikhs glorified their past by decorating Gurdwaras with paintings of Sikh Gurus, elaborating upon the aforementioned Mughal style.

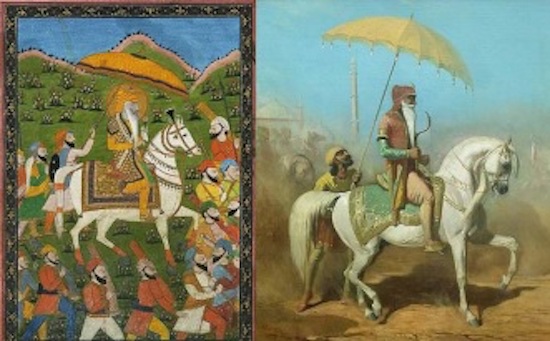

Ranjit Singh, Emperor of the Sikhs, was painted many times, in the Sikh style as well as European ones. Compare this Sikh School painting, with the nineteenth century French painter Alfred De Dreux’s. The latter was commissioned by General Jean-Baptiste Ventura, an Italian mercenary who served under both Napoleon and Ranjit Singh; and it’s clear De Dreux modelled his painting directly on the Sikh School one.

Ranjit Singh, Sikh School; Randjet Sing Baadour by Alfred De Dreux, 1838

They used watercolours, simple colour schemes, with the figure in some kind of action. While invaluable, these images did not create radical changes in the Sikh art market.

After Ranjit Singh died in 1839, the usual melodrama followed; eight sons vying for leadership, plots, backstabbings, factions; claims to legitimacy. Sikhs wanted a way of remembering their old emperor, and a way to press the claims of legitimate heirs to the throne. This is where August Schoefft comes in.

August Schoefft left Austria in the late 1830s, when it was still central to world affairs. His father, Josef Karl Schoefft, was a Hungarian painter, who did religious scenes for churches. Like his father, August Schoefft’s paintings would end up, eventually, on the walls of temples and ashrams the world over.

In about 1841, Schoefft made his way up to the Northern empire of the Sikhs, bringing with him a form of academic painting, which he had learned at the University of Vienna. Taught all across Europe as the way to paint, it favoured the ideal over the imperfect, the heroic over the mundane, and action over stasis. As such, while academic painting from the nineteenth century may have captured the down-to-earth good sense of the growing bourgeois classes in industrial Europe, to us it can seem unbearably kitsch. This is the style which eventually influenced the way Sikhs painted – and imagined – their Gurus.

Schoefft painted Sher Singh, also as propaganda. Sher, Ranjit’s son, is depicted as bold and enormous – his sword – which is also a Khanda – looms out of the painting, suggesting readiness to defend the Empire, and the Sikh religion.

It is radically different from what the Sikhs would have been used to – there is a calm but very real intensity to the sitter, visible as it would have been in real-life. It is not simply a rendering of Sher Singh – as would have been the case with a Sikh painting – but an attempt to portray something of his character.

Maharaja Sher Singh, By Schoefft

Schoefft secured his reputation among the Sikh elites by painting two large portraits of Ranjit Singh: one of his court, and one of the old emperor at prayer. Though these images were completed in Vienna, they were sketched out and initially painted in India, which was enough, Kerry Brown argues, to influence local Indian artists. Schoefft taxidermises Ranjit Singh and the entire preceding period: he celebrates a calmer age, when religious and political power were unified and embodied by a single individual; Sher Singh is painted with a Khanda, Ranjit Singh sitting before the Harmindar Sahib (the Golden Temple).

Ranjit Singh and the Golden Temple, by Schoefft

Ranjit Singh’s appearance did not match his glorious reputation: droopy-eyed from small-pox, a thinning beard, and short. This disappointed travelling Europeans, even describing the ‘Lion of Punjab’ as a mouse, probably why De Dreux focused on his horse. But Schoefft rejuvenates Ranjit Singh, simultaneously concealing his scarred face, and projecting the dead emperor as a pious man (despite his many, well-documented indiscretions). Wrapped in a white shawl (common dress for the pious), buried amongst royal guards, fellow worshippers, listening to a recitation of the Guru Granth Sahib, Ranjit Singh is a model of humility. The temple floats on the pool, the red bricks mellow in the evening light, prayer time in magic hour.

Both the Sikh community and Schoefft profited: Schoefft was able to make his paintings more competitive at home, by enhancing his mystique, and the Sikh communities enjoyed the new way of painting. Although other Europeans were influential such as Leopold Massard, Schoefft was the in-demand artist at the Sikh court. Indians were accustomed to Mughal paintings and miniatures; but Schoefft demonstrated that realist paintings could capture personal, historical and social energies. And it is this academic realism, and the move from water to oil paints, which had the biggest impact on the Sikh community, now demanding ‘Western’ paintings.

Break-ins to British Asian households is fairly normal; the South Asian diaspora typically keeps expensive jewellery at home. Thieves identify South Asian households in a curiously sensitive way: by looking through windows, for paintings, specifically for paintings of Hindu deities and Sikh Gurus. This is opportunism plain and simple. But it’s also a radical sort of art consumption; a kind of guerilla viewing. The paintings people hope to see are typically by Sobha Singh.

Sobha Singh (1901-1978), a Punjabi-born, self-taught painter began to paint Sikh Gurus using Western painting techniques, and transformed the way Sikhs imagine their Gurus.

Singh, impressed by Western paintings and portraits, saw the immediate appeal academic realism had on audiences. Furthermore, through Schoefft’s work, Singh saw his own community could already be included in such a practise. He painted scenes of Punjabi folklore as well as Sikh Gurus, using the in-demand techniques: oil paints, single-point perspective, and rendering of realistic subjects in ‘action’.

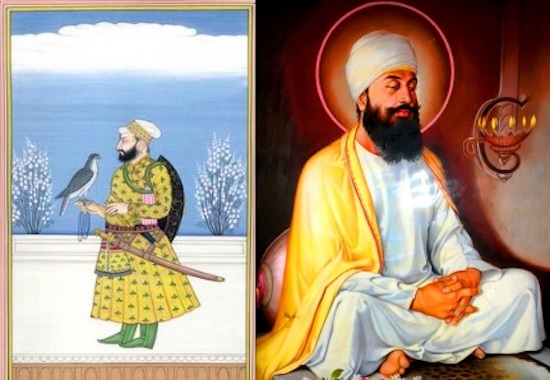

Inspired by a belief in naive goodness, Singh’s paintings were deliberately populist. He was an instant sensation, fulfilling popular expectations of Gurus and receiving commissions for more. Like figures in other academic realist paintings, Singh’s Gurus were idealised, and in action. Guru Angad is seated on the ground, preparing the first important text of Sikhism; Tegh Bahadur meditates, his unearthly calm foreshadowing imminent martyrdom; Guru Gobind Singh with resplendent before his fort. His works were reproduced en masse in Amritsar, and disseminated widely.

Guru Tegh Bahadur by the Sikh School; Guru Tegh Bahadur by Sobha Singh. Courtesy the Sobha Singh Estate, credited to Sobha Singh, distributed by Sobha Singh Art Gallery

Singh’s paintings animated the lives of the Gurus through real-looking-people; fitting for the Sikh belief that Gurus were ordinary, but special, people.

Singh did face criticism however; much like his academic realist forebears, his work was dismissed as bourgeois and sentimental, isolated from the reality of harsh, indigent Indian life.

Guru Gobind Singh, unknown Sikh School artist CA 1810, Guru Gobind Singh, Sobha Singh CA 1960. Courtesy the Sobha Singh Estate, credited to Sobha Singh, distributed by Sobha Singh Art Gallery

Singh’s works had an interesting impact on Sikhs, especially in the diaspora; they unified Sikh conceptions of Gurus. Singh’s portraits have enabled Sikhs to easily and quickly identify mainstream Sikhism from other forms of the religion. During its conception, no serious distinction was made between ‘mainstream’ and offshoot Sikhism. Indeed, it only became a consolidated religion in the Western sense in the last 150 years, thanks to British forms of categorisation, and self-generated ‘propaganda’ such as Sobha Singh’s paintings.

Guru Nanak Dev meeting Hindu Holy men, Early Sikh School, Google Cultural Institute, Guru Nanak Dev Ji, by Sobha Singh. Courtesy the Sobha Singh Estate, credited to Sobha Singh, distributed by Sobha Singh Art Gallery

For example, in 2007, a textbook in New York had to be reissued since it used a nineteenth century depiction of Guru Nanak – one which jarred with twenty-first century Sikh conceptions of the Guru. The nineteenth-century image showed Nanak as a Sufi mystic, by whom Nanak was deeply influenced. Nevertheless, Sikhs could not tolerate such an idea, and the textbook was reissued with a more familiar image later. Ironic, since the earlier image was a lot closer to how Early Sikh Art conceived of Nanak: a mystic, and an experimenter, not a figure that conformed to expectations.

Such was the success of this vision, when Eliot painted his fresco in Espanola, he painted Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh in the same poses, figurations, and colours as in Sobha Singh’s portraits; so we may conjecture Yogi Bhajan brought with him reproductions of Sobha Singh’s works..

Many other Sikh artists followed Sobha Singh’s lead in using an academic realist style to portray Gurus, and their paintings have also become popular. Gurbux Singh, as noted above, even directly used David’s modelling of Napoleon for his painting of Guru Gobind Singh.

Napoleon also continues to figure in the story of Sikh paintings, in other ways. Manu Kaur Saluja, a contemporary American artist produced a painting of Ranjit Singh inspired by Ingres’ composition of

Napoleon. Saluja created an intentionally iconic, idealized young Ranjit Singh: a man, not a mouse who recruited soldiers from Napoleon’s army. She also created a replica of F. X. Winterhalter’s portrait of Duleep Singh, Ranjit Singh’s son; something Sobha Singh also did. Her paintings hung together in a 2009 exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum titled “Kings of Punjab”. While Sobha Singh was impressed by Winterhalter’s vision of the Sikh prince, Saluja encapsulated the changing fortunes of Sikh power in the nineteenth century: Power modelled on both Western and Sikh ideas.

Ingres’ Napoleon CA 1806; Ranjt Singh by Manu Saluja, 2009

Schoefft brought oil paints to the Sikh Kingdom, and painted Ranjit Singh; Sobha Singh inherited this style, and turned to parochial images of folklore and religion. These paintings effected a cultural shift; Sikhs went from imagining their Gurus, to developing standard representations of them. As Sikh conceptions of both Gurus and rulers have been influenced or even taken from Western paintings, and these paintings influence Kundalini artists in the West, does that mean these paintings are being culturally appropriated?

The fourth Sikh Guru, Ram Das is also revered in Kundalini Yoga. Compare the following paintings of Ram Das.

Ram Das, Sikh School CA 1800; Ram Das by unknown CA 1960; Ram Das by Kundalini Artist CA 2005

The first was painted in India, during the Mughal Empire, circa 1800, by an unknown Sikh artist. The second is by a Sikh artist influenced by Sobha Singh. The third is produced by a Kundalini artist for their ashram in the US, and was painted this century.

There are some clear differences between the first and third images. The Kundalini portrait incorporates a mantra in the background, which invokes Guru Ram Das as a being on par with God (Waheguru) – something Sikhs would never do. The Kundalini portrait also incorporates a symbolism not found elsewhere in Sikh portraiture, of flowers dropping like tears from the Guru’s eyes. But the composition of the Kundalini portrait is more similar to the second portrait, than to the first. The first is distinct in the positioning of the subject, as well as his characterisation (beard colour, facial features); the second resembles familiar, Renaissance-style portraiture, as does the third.

Therefore, not only is Guru Ram Das’s status different in Sikhism and Kundalini Yoga, he is portrayed differently; has he, along with Sikhism been appropriated?

The story is complex. Kundalini yoga artists are imagining Gurus, which are themselves based on imagined paintings, which take their schemes and materials from Western painting traditions. Sikhs have made these paintings despite not venerating representation, and Yogis have made paintings by ignoring the very real sensitivities of Sikhs and Hindus, but also in earnest spiritual seeking.

As such, the questions around appropriation should be treated with caution: While there are real issues of sensitivity and power-relations, understanding the political and historical context of an object’s making, gives us a clearer idea of how messy and dynamic cultures are. This should help us acknowledges Sikh claims to misrepresentation, but also one which acknowledges the nature of cultural diffusion.

Gurmeet Singh is a writer and editor living and working in Berlin. He writes mostly on culture, technology and politics, and is also currently writing his first novel