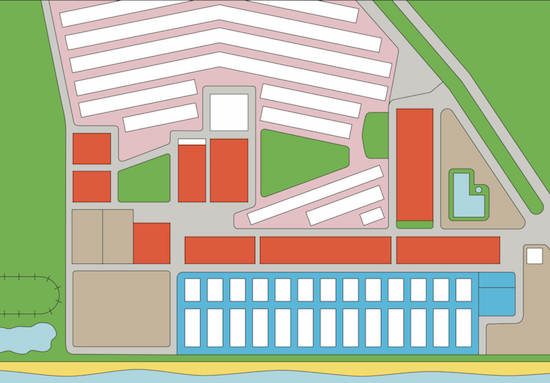

Scott King, Britlins Frigg, 2018, courtesy the artist and Herald St

A declaration of interest: Scott King’s current project makes reference to British New Towns and holiday camps that have a deep personal resonance because I come from East Kilbride; we then later moved to Jaywick on the Essex coast. There we were close to the Butlin’s resort at Clacton-on- Sea. This poundstretching paradise shut its gates in 1983, not long after our flit. My recovery from such trauma has been prolonged and long suppressed memories have been reawakened by King’s show. He has slyly mutated Billy Butlin’s idea of the great British family holiday package and come up with a new twist for the Brexit age, a utopian plan for twenty-first century UK living. With a straight face he calls this development “Britlin’s”.

The first wave of Brexit fixated artwork is now upon us – it can only be a matter of time before there is a contrived term for this phenomenon such as BrexArt. Thump those you hear uttering any such. First off the blocks was the gamey bile of the Scobberlotchers album (2016) by Momus. We can point too at the scabrous collages seen online by @Coldwar_Steve, the John Heartfield of our time. As for literature there is the disturbed dystopian East Anglian landscapes of Sam Byers’ Perfidious Albion (2018) and Jonathan Coe’s highly anticipated new novel Middle England. And now this latest arrival – King’s most recent iteration of Britlin’s to be found here at Firstsite, Colchester.

King’s putative Britlin developments include the planning of more New Towns, each named after Anglo-Saxon gods and goddesses as with Saxnot in West Sussex, Balder in Lincolnshire, Loki in Yorkshire – and here in Colchester we see the plans for Frigg, Essex. Firstly there is a large wall mounted schematic plan done in bold colours, the design based on that of the aforementioned holiday camp at Clacton-on-Sea. And what delights await you in this New Town? A gleaming life of promise in Essex, in case you couldn’t tell, where “the past is now”. A place where all your nostalgic needs are addressed, where “you will know your neighbours, where holidays are at home and not abroad”, where we are told with placatory insistence that “your past is your future”.

On a nearby screen we see the faux promotional video Come to Frigg (2018), a collaboration made with filmmaker Paul Kelly, which sees a Britlin’s representative outline the charms of relocation to the New Town. The man wears thick-framed glasses to lend him some authority however a mustard coloured shirt and an orange floral tie undermine his trustworthiness. He speaks with urgency and belief – “if you are worried that you can’t go back to the past then you are WRONG!” He lectures us convincingly about the New Town having the strict morality and the low prices of days gone by. He promises fun and talks enthusiastically of community spirit with the excitement of all day Bingo and revived knobbly knee contests. He tells us that Frigg is a place where – “you will know where you belong”. What the man says is delusional and quite deranged.

Scott King, Frigg – Site Map, 2018, Courtesy the artist and Herald St

And yet, clearly, there is an appetite for such regression. On some cans hanging from the walls you can listen to taped interviews that feature real people who used to work at the Butlin’s camps. You can hear the wistfulness in their voices as they reminisce about the 1950s and 60s.

But King’s work has a deliberate layer of equivocation. Some will see the show and sigh and leave thinking – ‘ah, if only’. Those of us who grew up in New Towns will recognize the daffy optimism of their early years in existence, the time before their degradation and decline as scorchingly soundtracked by the likes of the Jesus and Mary Chain.

Britlin’s is a world that recalls the poignant disappointments of George Bowling in Orwell’s Coming up for Air (1939) with his desperate search for reassurance in the face of imminent disaster, his pining for some mythical past where the sun shines on slow flowing rivers and the pike bite. King’s ambiguities highlight the dissonance for those with memories of what Saint Etienne hymn as a ‘Sweet Arcadia’, from their album Home Counties (2017) (the cover of which, incidentally, is also by King) and the crummy reality of twenty-first century Britain with its echoing high streets, its food banks, its ongoing tragedy of mass homelessness.

The nostalgic melodies at work in Britlin’s aiming to conjure the past do not sound remotely like those spookily drifting miasmas of The Caretaker for example, his distortions of 1930s dance hall tunes, nor do they resemble the out of kilter strangeness of Ghostbox productions. No, the specific soundtrack to Britlin’s is to be found on the Bell Records label perhaps, or Chinn and Chapman stuff like The Sweet from the 1970s – specifically their smash hit ‘Blockbuster’. The faded patina of Glam Rock haunts King’s revisions. King had worked previously with the best band of the 1990s – Earl Brutus – his designs chiming with their manic glitter stomp. His cheeky tribute to them here – You Are Your Own Reaction (2018) – references a line in their anthemic masterpiece – ‘The SAS and the Glam that Goes with It’ from the album Tonight You Are The Special One (1998). This work is an installation where the floor to ceiling windows at Firstsite are subversively transformed – stained glass style – by brightly coloured vinyl coatings. Scarlet, rapeseed yellow, apple green and cobalt blue panes cast a deliberately archaic, reactionary, ecclesiastical air onto architect Rafael Viñoly’s ‘post-postmodern’ surfaces.

The Britlin’s project is a sardonic take on the fantastical delusions of Faragism. King knows that irony, as Czeslaw Miłosz wrote, is the glory of slaves and knows too that right now the British may be staring at social/cultural crucifixion. Right now it is no comfort to say to each other that we are all Spartacus. King’s ideas for revived holiday parks and new New Towns are a distorting funfair mirror reflecting the desires of the Murdoch maddened mob; a sad and lost Britain where people seem content to die on those knobbly knees.