When her answer arrived, it was just two words stamped on a postcard: “Nichts neues”. Undaunted, the curators planning Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt’s major retrospective pressed the 91-year-old artist about any recent pieces she’d like displayed – only to receive once more the same terse retort via postcard: “Nothing new”.

Never one to get lost in translation, pioneering visual artist Wolf-Rehfeldt laboured fearlessly behind the Iron Curtain for decades as she forged intriguing new intersections between poetry, graphic design and optical art. Now, a lifetime of her beguiling and cerebral works are on display in the newly-opened Das Minsk museum in Potsdam.

A short train ride from Berlin, the exhibition sees her earthy 60s psychedelic paintings in the style of Arthur Dove sit alongside her typewriter and collage mail art from the late 80s. It’s the second exhibition at the museum – a former GDR-era Belarusian restaurant originally called ‘Minsk’ – after it was left to rot for decades by the city’s cash-strapped government. Now, its extensive collection of works by Wolf-Rehfeldt and fellow GDR artists Wolfgang Mattheuer and Bernhard Heisig will serve as the impetus for its new incarnation.

Despite her many years of silence, the journey back from relative obscurity for Wolf-Rehfeldt to this major retrospective can be traced to the efforts of art historian Zanna Gilbert and dealer Jennifer Chert, as well as the exhibition’s curators, Paola Malavassi and Marie Gerbaulet. All have championed the minimal yet powerful multi-disciplinary art of Wolf-Rehfeldt. “The topics she raises and the questions she asks through her art are still highly relevant today,” Malavassi tells me.

The curators spent more than four years working closely with Wolf-Rehfeldt to select the 200 works on display – even down to the repetitive typewriter characters that were used for its dizzying wallpaper. “We still struggle with the same issues and questions that she typed into her typewriter some 40 years ago,” Gerbaulet says. Those themes include her reflections on the environmental crisis, civil rights, war and technology, as well as more introspective musings on the poetic use of language and typography.

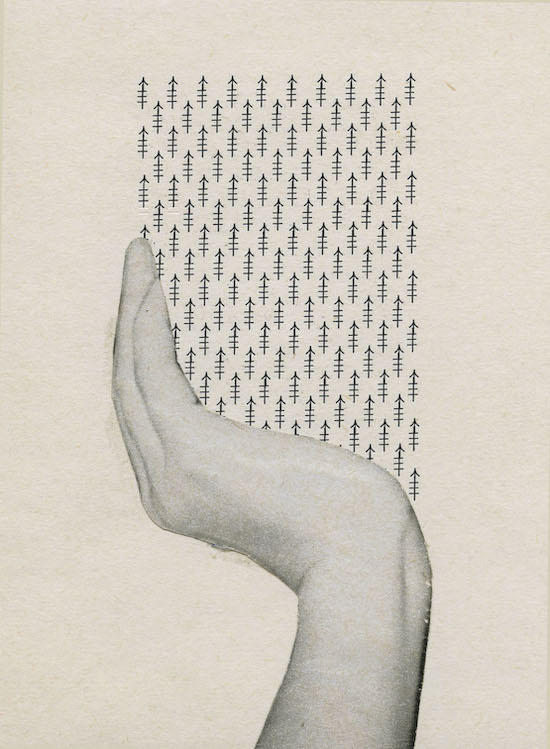

First impressions can be deceiving in Wolf-Rehfeldt’s artwork. Her approach in Save Nature 2 is to create order with the typewriter’s limited characters in forming larger patterns and meanings. The collaged helping hand meets her keystrokes to turn a barrage of arrows and plus signs into a forest to cherish. Elsewhere, she picks apart words – letter by letter – to extrapolate new meanings and create complex visual puzzles. While the finished work appears deceptively simple, the premeditation and patience involved would have been nothing short of spectacular given the typewriter’s limitations.

Born in Wurzen, Wolf-Rehfeldt taught herself to type as a teenager, before beginning an apprenticeship as an industrial clerk in 1947. In the 50s, she moved to Berlin where she met her future husband and fellow artist Robert Rehfeldt. In the early 60s, she began to write poetry as her interest in language and semiotics via the typewriter began to fixate her. And from 1974, it was husband Robert who created their links to the worldwide ‘Mail Art’ network, which included fellow artists Joseph Beuys and Kurt Schwitters (whose postal works are now in the collection of the Tate). While Wolf-Rehfeldt’s playful word-focused postcards and correspondence were busy turning heads across the globe, they risked falling foul of repressive GDR officials. Yet by distributing her artworks freely via mail, she skilfully evaded the state censors.

Wolf-Rehfeldt used the typewriter with frightening – and often humorous – precision. Malavassi describes her virtuosity with the machine “like a pianist pulling sound from the keys of the instrument”. With one eye on the larger composition, she had an “awareness for the interplay of signs, for the required pressure of the fingers on every key, with a deep knowledge of how the imprint of every key on the paper can impact the work”.

Wolf-Rehfeldt speaks for a “deep understanding of the machine, language, signs and their visual power,” Gerbaulet says. “Her works don’t raise simple questions with clear answers – but encourage a deep reflection and lead to the formation of one’s own inner attitude. How do we deal with environmental issues? How do we cope with today’s information society? How can we stay human in a world that is increasingly technologically engineered?”

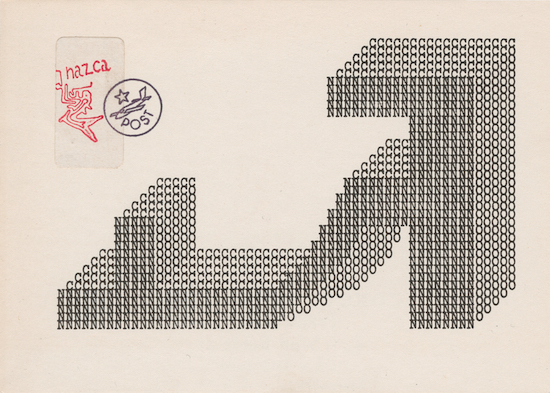

In Betonierung_2, Wolf-Rehfeldt uses the letters of the title word (it means ‘concreting’ in German) as building blocks to create a dense geometric shape. This organic reflection feels both beautiful and oppressive as an optical trick. Nevertheless, her ability to suck the viewer into the cascading layers of her mischief-making is a wonder. Your eyes will urge you to get as close as possible to decipher each message on the small works on paper. Magnifying glasses are available.

As the regime in East Germany folded, the global mail network also started to fade away. For Wolf-Rehfeldt, her new geographical freedoms irrevocably changed her process of making and distributing art. Meanwhile, the age of the computer and the internet started to revolutionise graphics and communication. A few years later, her husband Robert died. And soon after, the artistic chapter of her life closed.

Since then – nothing new. She did briefly experiment with Xerox machines but soon stopped making art altogether, saying it was “no longer possible”. Or as Malavassi surmised: “When an artist is so far ahead of their time, it’s only logical to stop producing when they choose.”

As you exit the museum, you’ll spot one of her final works – a large-scale outdoor mosaic titled Cagy Being (Käfigwesen) 3. It was originally planned for a kindergarten in 1989 but was only realised thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Depicting five children in geometric abstract form, it speaks to Wolf-Rehfeldt’s many reflections on the illusory promise of freedom and the joy of inner fulfilment. Or, as she once remarked: “We’re all in a cage – sometimes so big you can’t see it.”

Even with the spotlight falling on her life’s work, it’s noticeable that Wolf-Rehfeldt is nowhere to be found in the exhibition. But if you search hard enough, you’ll find a solitary image of her on Page 104 of the accompanying catalogue – a charmingly old and grainy black and white portrait taken outside a post office by her husband. As ever, nothing new.

Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, Nichts Neues, is at Das Minsk in Potsdam until 7 May