Donald Byrd 1962, Roy DeCarava © The Estate of Roy DeCarava. All rights reserved. Courtesy David Zwirner

Roy DeCarava’s photographs were shot mostly on the street. But as he said himself, they were “made in the dark room” through a meticulous yet intuitive process. They are not quite black and white, more tones of grey that rarely put a firm foot into either extreme. His images can seem teased out of the darkness, sitting somewhere between documentary and abstraction. Trained formally in painting and drawing, DeCarava picked up the camera in the 1940s and applied his vision to the process of photographic image-making.

DeCarava, who passed away in 2009, was hugely successful in his lifetime. He had his first solo show in 1950 at the Forty-Fourth Street Gallery and two years later he was the first African American to be awarded the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship. He was also acquired and exhibited at MoMA and all over the United States as well as internationally. He taught at Hunter College and the City University of New York and he also created a book of images alongside the poetry of Langston Hughes.

Born in Harlem at the end of 1919, DeCarava grew up in a New York on the cusp of prosperity. The birth of New York as a city and the New York of the mind was born out of both creative labour and hard, physical toil. His images of the city show a city unseen, partly as he was often capturing the Black experience and partly due to his unique eye for the dark and the uncanny. Whether a double bassist, a child playing out on the street, or a labourer holding their tools as they sit on the train home.

During the years DeCarava was photographing the city, workers, painters, artists, and writers flocked to New York – a city on the rise but still filled with pockets of poverty and hardship (as it has today). In his photographs you see Central Park, 5th Avenue, and Harlem through his eyes and his view of beauty has a definite darkness to it.

DeCarava took many photographs of musicians performing in jazz clubs including Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, Ornett Coleman, Duke Ellington and John Coltrane.

Six figures in sunlight 1985, Roy DeCarava © The Estate of Roy DeCarava. All rights reserved. Courtesy David Zwirner

“It was an amazing period, often when I used to lecture more frequently I would tell people ‘you know, geniuses would walk the streets’,” DeCarava’s widow, art historian Sherry Turner DeCarava, said to me when we sat down together in the gallery.

Onstage, these great musicians appear both lost and found, sometimes drenched in sweat as though they have emerged from battle, at other times lost in ecstasy, having played on for hours. There is a sense of the labour of creativity, a palpable sense that something is being made in the moment DeCarava chose to take the photograph.

Sherry recalls a moment when a club was empty, closing, and Coltrane played on and on. “Basically they gradually closed the club down. It got later and later but Roy was still there. The owner put the chairs up on the table, he photographed the chairs. There was no crowd and ‘Trane just kept climbing and climbing. He wasn’t finished until he was finished.”

The feeling we get of the time is that this was about the pure art of making music, a new language of sound which was about pushing creativity as far as it could go, in the moment. A kind of live, raw and exposed creativity that was about being in a certain space, in a certain place, at a certain instant. You can imagine the musicians freestyling long into the night, searching for that perfect sound, and DeCarava sitting there, listening and waiting for that sublime visual moment as they played.

His offstage portraits make these legends of the jazz era seem approachable and warm. They are snapshots of friends – albeit ones who seem to have an extra spark in their eyes, like some kind of mysterious x factor. You get the sense that DeCarava was one of them, part of a group rather than a fly-on-the-wall observer, which is how he managed to capture Billie Holiday laughing at a house party or jamming at the piano after hours. He knew all the musicians but was closest to Coltrane.

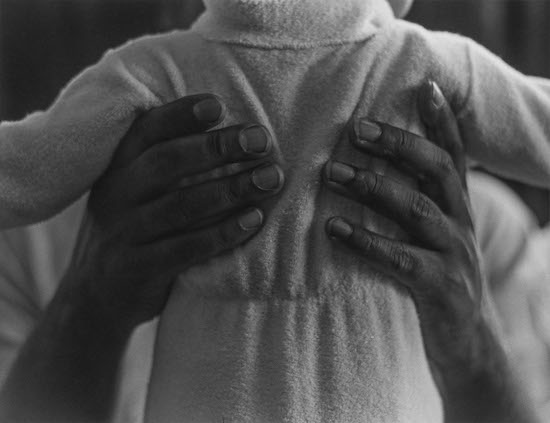

Bill and son 1962, Roy DeCarava © The Estate of Roy DeCarava. All rights reserved. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner. Courtesy David Zwirner

“It was a rare match,” recalls Sherry. “He photographed him over and over and over and followed him to various cities when he was performing and at some point, during rehearsal Trane looked up and he said, ‘Ah! You again’ and with a kind of gentle friendliness. So then they sat down and they talked.”

The two artists shared creative friendship which offered some camaraderie in the isolation of creative work at a time when jazz was exciting the world and the city of New York as we know it was coming into being.

Sherry recalled the symbiotic friendship which she feels was unique to its time. “We felt he had this depth that was unfathomable, just a depth of generosity, a depth of exploration and [Roy] shared that in photography. So he was very attracted to Trane and Trane was very appreciative.

“We, you know, we think about artists competing for bandwidth and celebrity status and who you’re seen with, but that was a cultural moment in time. Americans – and maybe the French and Swiss also – understand, because jazz was everywhere and the great performers were still alive so it was possible to have a relationship like that, between two artists.”

There is something deep about DeCarava’s images, you can look into them and find many different things, either through their composition or their content. They provide an unseen commentary on Black America. They are also a multifaceted portrait of a time and a place that captures the energy, creativity, graft, and beauty of life at that moment.

Roy DeCarava, Selected Works, is at David Zwirner, London, until 19 February