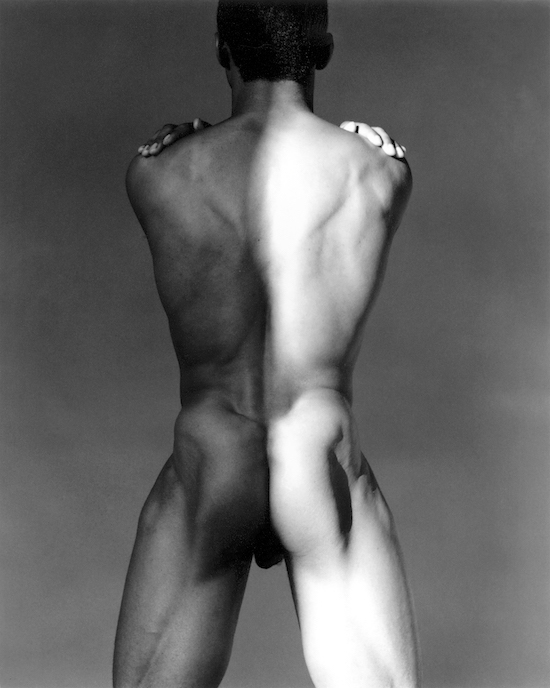

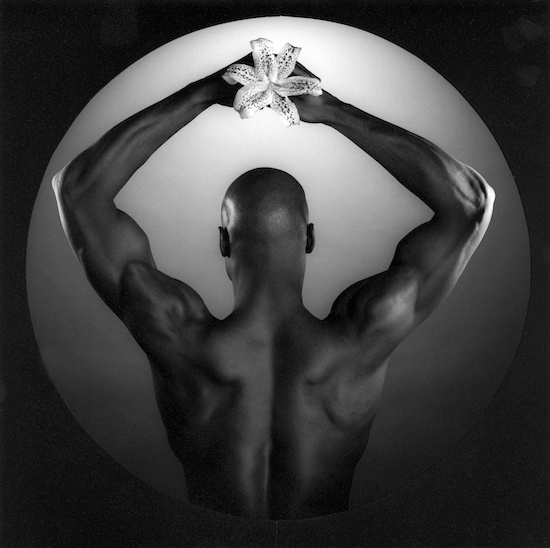

In September 1989, Senator Jesse Helms stood in front of America’s press and fellow politicians clutching a selection of black and white photographs by the artist Robert Mapplethorpe. "Look at the pictures," he demanded furiously. "Look at the pictures." Mapplethorpe had been dead for six months, but his now-iconic and unapologetic images of rubber-clad, naked men were instigating a lawsuit against a Philadelphia museum and igniting America’s culture wars. In death, his ability to provoke was more powerful than ever. "Robert Mapplethorpe was a known homosexual who died of AIDS," continues Senator Helms. "I don’t even acknowledge him as an artist."

It’s with this scandal that Randy Barbato and Fenton Bailey introduce us to the subject of their new biopic, instantly reminding us how Mapplethorpe was able to enrage through art, and demanding that we too, over the course of two hours, look at the pictures. Barbato and Bailey’s film is released as twin retrospectives of Mapplethorpe’s work open at the Getty Centre and Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It acts almost as an accompanying piece, delving deep into Mapplethorpe’s life and persona via testimonies from those that knew him best: his friends, family and lovers. But why choose this moment to focus on Mapplethorpe and his work?

"Robbert Mapplethorpe always talked about how art is about opening people’s minds and right now, more than ever, American minds are closing," says Barbato. "We’re at this interesting crossroads and I think his work is incredibly relevant again. Especially his challenging work, his explicit work."

The time is also ripe for taking stock of a bygone New York and an art scene that will never again be replicated. "New York in the 70s and 80s was a horrible place to live," says Bailey, who lived in the East Village with Barbato during that time. "It was squalid, but a lot of artists lived there because they couldn’t afford to live anywhere else. It was this default community and out of this fetid urban thing came all these artists, not just Robert Mapplethorpe, but Andy Warhol, rap music, punk. It was an enormous bumper harvest of creativity and I think it appeals to people now because it was pre-AIDS, pre-Internet, pre-gentrification. Now, a full generation later, we can look back on it as a golden age."

In the years since, we have become increasingly exposed and, arguably, desensitised to sexually explicit imagery, but Mapplethorpe’s frank depictions of sexuality and the male nude remain as confronting and affecting as ever.

"Mapplethorpe’s work has the same impact as it had 27 years ago, and I think that’s because we live in this split personality culture: we’re completely porn-saturated and have access to all this imagery, but it’s in the privacy of our own homes," says Barbato. "We do it in this very closeted way, so it’s about context. It’s about watching a film with this explicit stuff in it and about seeing it so beautifully composed that it touches a different nerve than someone just looking at naughty pictures in their bedroom."

Shocking is perhaps too lazy, too one-dimensional a word to describe Mapplethorpe’s work, yet it’s the one we most often reach for. Mapplethorpe himself wasn’t much of a fan of it, saying in the year before his death: "I don’t like that particular word, ‘shocking’. I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before."

"He was just incredibly curious," says Barbato. "When he became interested and obsessed with S&M, so did his portfolio. When he became obsessed with black men, so did his portfolio. His work always reflected his current obsessions and curiosities."

That’s not to say Mapplethorpe was blind to the shock factor his work possessed, or to the reaction that it could provoke in people.

"I think his use of shock was strategic," says Bailey. "It was about getting people to open up, it was to be memorable and ultimately so that people would take his work seriously as art."

As a student, Mapplethorpe himself admitted to being a snob about photography, deeming it like so many others as a "lesser art form". But Mapplethorpe was instrumental in elevating photography’s reputation, not only with his explicit images, but with his more classical portraits of nudes and images of flowers. "Mapplethorpe is crucial in the transformation of photography from hobby or trade to a recognised art form," says Barbato. "Without him it would have happened, but probably not as quickly."

If there’s one overriding thing that this film reveals about Mapplethorpe, it’s how unabashedly ambitious he was. He was manipulative and fame-hungry – and this is something it’s easy, or perhaps more convenient, to forget. In the same way that we romanticise the squalor of 80s New York, we like to imagine our artists are somehow above that grubby desire for money and stardom.

"We’re not used to our artists being honest about their ambition and I think that’s what makes him controversial for many people", says Barbato. "When you do these kind of bios, people want to fall in love [with the subject]. But so often storytellers think that to fall in love with someone you have to pretend that they aren’t human. There are some people who have said ‘Oh, I don’t know if I like him’ after the film and maybe it’s because they’ve seen so many portrayals of people that are false. For me, Mapplethorpe is interesting and admirable because of his brutal honesty. Not just in the work that he produced, but in the life that he lived."

Indeed, Mapplethorpe’s art and life were inextricably entwined. "Theirs was a life being recorded," Sandy Daly says of Mapplethorpe and his lover Patti Smith at one point in the film. And now, of course, in the age of Instagram and reality TV, every life is lived in this way, obsessively documented and shared.

"Mapplethorpe said the life he was leading was more important than the pictures he was taking," says Bailey. "And at other times he said his life was the work of art. So what does that mean? If the life is the work of art, then the pictures are just recording or documenting a life. And that’s the same way he adopted writers and journalists to write about him, so they could document this ultimate work of art – his life."

Mapplethorpe: Look At The Pictures opens at the ICA this weekend