Every photocopy is a document. Even the blank paper accidentally copied. That’s a document of the process, of the light of the lens, or of the ‘mistake’ itself. I’m not sure if what I do is an exercise in nostalgia. Process is the key, and the act of surrendering to that process has certainly guided me.

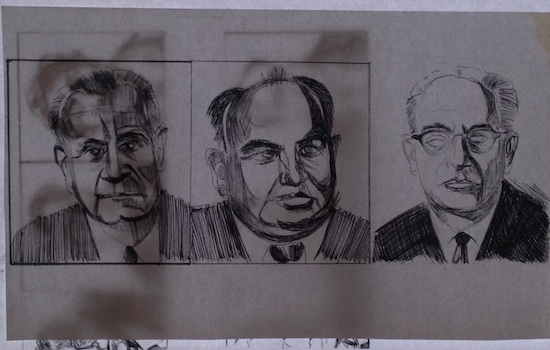

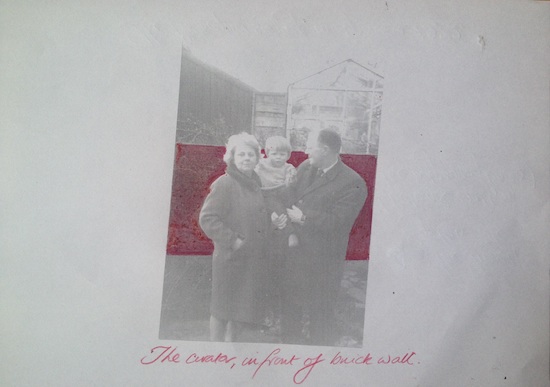

Consider this: although some of the pictures I produce contain representations of ‘me’ as I was, they’re normally taken from drawings of old photographs that are then put through the memory filter of the photocopier. It’s an image created by me that is then, potentially, recreated ad infinitum and becomes less about me as the toner runs out.

Maybe the marriage of my pictures and the never-ending process they are subjected to proves nothing is real. Outside of the fact you now possess an original photocopy.

Inner Visions

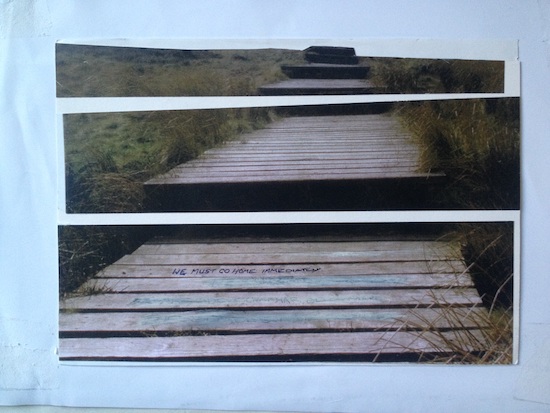

My work often shows my parents’ garden in Accrington, an industrial/agricultural town in the north of England. We’d moved to a bigger house to escape the incessant noise of the night shift at the Empire Mill, a monstrous Victorian cotton mill-cum-card factory that backed onto the 1930s bungalow my parents were living in. The new house’s garden (overlooking Nori brickworks and the field where the nascent reformed Accrington Stanley FC (1968) played), was spacious. Thanks to my mother’s green fingers it has changed radically over time but the main constituents have remained broadly the same. The ‘backs’, (a narrow strip of no-man’s land behind the house), the coal bunker, the shed, the 1920s wooden trellis between front and back, and the flaming red Accrington brick wall separating us from our neighbours. It became a haven, bringing protection in an increasingly complicated world. I decided to start recording it and photocopying the results

I have been fascinated by photocopying since the mid 1980s. Not driven by any art movement (I certainly had no knowledge of the xerox art of the 1960s and 70s) but, I suppose by curiosity born of living in a bubble. The simple process of instantly creating a new image out of an existing one – initially done to send to friends, as an amusing addition to a standard letter – served as a vehicle for two journeys: one opening up a previously untapped inner world, the other helping me find a set of social buoys I could cling to in an often unforgiving outer world.

When I first made copies of my drawings in the local library (at two new pence a pop on a slightly scary apparatus that looked like a washing machine), I instantly felt they appeared more real and surreal. It was a shock. It is hard to describe your reaction to the changes you see in a work that you originally made, especially after a machine has had a crack at reproducing it. Lines that felt perfect and satisfying when committed to paper could suddenly look thin and indecisive when flattened. Was this an impersonal judgement on ability?

But, as they appeared in the tray the reproductions suddenly felt public, manufactured, fresh off the production line and, most importantly, in the world. And that ultimately was a good thing. It was a decision. As an artist you couldn’t really go back to a state of unknowing. The photocopying process also removed the personal elements one by one, flattening the lines, hiding some marks, or accentuating others. Rather than having the image touched up or refined to hide hitherto unseen mistakes or deleted, as is the case with much contemporary digital art, the brutality of the copies helped define and maybe reaffirm the essentials of the work.

There was another unlooked for development. Slowly, by making more photocopies of the same image, I noticed I disappeared from both my own work and the process. I liked that. I also liked the fact that, due to this process, each photocopy is unique. That’s why I still sign the photocopies I give away as ‘a unique photocopy’. A little joke born in part of the shock of those first encounters.

It is also why I still prefer to use sketches or simple pen or pencil drawings, not finished works, in my photocopying art. This isn’t an admission of sloppiness, nor an acceptance of incompleteness. Rather, I like the roughness and the directness. By dissolving parts of the line, other parts are uncovered. This is maybe why I avoid coloured photocopies, preferring to cut up magazines to add colour or tone. There is something not quite right about colour photocopies, though some very early colour copies (done in the hope of landing a commission with some London arts agency back in the weird post-Thatcherite London of the early 90s) always had a gloriously cheap yellow bleed.

We Could Send Letters

One brilliant thing about photocopying was its social potential, first noticed in the way it saved time round writing letters, drastically enlivening the process along the way. Back then, writing to someone would take a day’s worth of sighing and moping, usually whilst listening to The Pale Saints’ debut LP. By using photocopies, all that naff, sub-Merchant Ivory crap about using green ink on coloured paper as a sign of being arty and sensitive could be jettisoned in favour of radical displays of mirth and mystery. Letters became increasingly complex. Friends who moved to the south would hide their first-job fears by decorating their missives full of pritt-sticked printouts.

I have a hoard of remarkable examples from the early 1990s, ones that I still use today in lectures and ‘happenings’. One belter contrasts an image of the provincial comedian Justin Toper with a number of astrological charts. Another notes the passing of a local councillor next to primitive computer artworks depicting elongated cows. Another ingenious friend used stamp-shaped photocopies of the head of Johnny Marr to pay for the post. I have them still, as fresh and juvenile as they were then, the originals locked safely away and a stash of copies ready for future projects.

Interzones

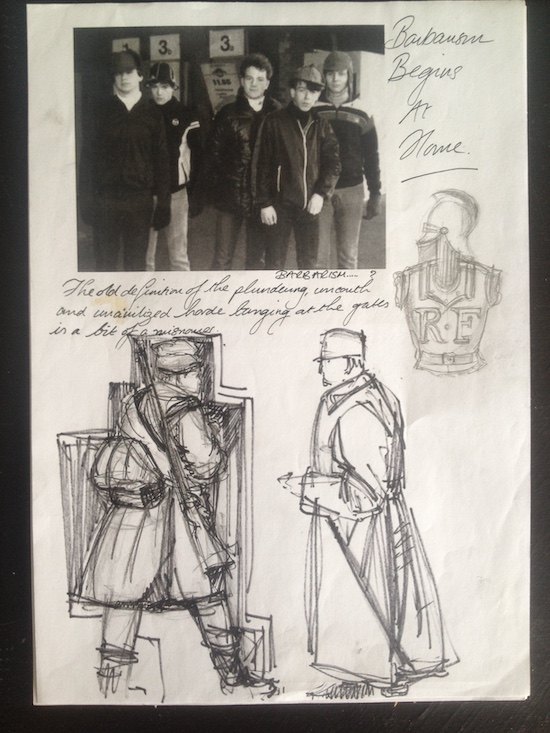

Friends were one thing, but the wider world? Here, too photocopies played a vital role in kick-starting my artistic practise. Back in the mid-to-late 1980s, finding out about things seemed impossible. As did escaping from a world that encompassed your violent hometown and the equally violent one down the road. Once in a while, whole new vistas would open up when funds permitted a brief and bewildering sojourn in a city such as Manchester, Leeds, Newcastle and Liverpool.

These trips would mean a scout round places such as News From Nowhere in Liverpool, Affleck’s Palace in Manchester or Astonishing Sounds in Blackburn, where you could pick up all sorts of information and an ill-fitting suede jacket to boot. Gigs were a great source of material too. Events where someone with hair that looked like an exploded cactus would sell you a stapled bundle of paper, normally with something about The Pooh Sticks in it.

Back then, reproduction culture was often about documenting the very recent, if not immediate past. Reissue mania in the alternative world was very much in its infancy. Music disappeared into the ether back then, and the histories and back catalogues we are so familiar with today could often only be found, with great vats of patience and no little luck, at a local library.

In the 1980s, tapes and fanzines were a vital bridge to other, wider scenes that had often not stepped out of their older siblings’ bedrooms. Visiting the infamous tape shop on Oxford Road in Manchester (overseen by a genial greybeard who sold me stacks of BBC In Concert C90s for a quid a go) was a way of catching up on music and bands that you were five years too young to catch, stuff like Magazine or Devo. Even better, all the inlays were photocopied, the tape fronts displaying images that only increased the mystery. These non-pictures were, in retrospect, glorious; gloomy paper cadavers that could have haunted the background of a Gustave Doré or John Cruikshank illustration. Images of a young mascaraed Jim Kerr would somehow, through the process of continual photocopy, end up looking like one of the murdered daughters of Tsar Nicholas II.

Football matches were another place to collect interesting information masquerading as cheap paper. Liverpool FC’s The End was a classic fanzine which, if memory serves was pretty well printed. And funny. Not that I was ever arsed about Liverpool FC (who won everything all the time back then) but there was something spiky and wide-ranging about the content which was mirrored in Manchester’s Freaky Dancing which I did like and was, I suppose, the younger cousin of City Fun, old copies of which I remember being on sale in a shop on Blackburn market for an eye-watering two quid a pop (as Joy Division nostalgia was reaching its first, mid-to-late 80s peak).

These were the days of underground fan clubs, of those in the know passing on info to an invisible spider’s web of like-minded people who would probably never ever meet in real life. And that meant the content was secondary in many ways, outside of letting you know there was another world out there – somewhere. Even if that world was as small and bubble-like as yours.

I remember the envelope for one edition of Echoing The Bunnymen fanzine, something I subscribed to in the mid 80s, displaying the spelling of my hometown as “Accrinten”; a true and glorious case of Scouse phonetics in action.

The Future: Totemistic Musical Objects, Safe Spaces and Exploding Paper

It’s easy enough to endlessly indulge in memories about the past to justify the present but how does photocopying currently operate as a socio-cultural act? The initial USP of the copier and photocopying – that the process created copies that acted as vehicles to reproduce, regulate and disseminate information – has been overtaken by the twin forces of the smart printer and digital technology in general. But that doesn’t mean the machines are redundant outside of city centre printing shops. There are pathways into a new world of photocopying.

In some ways, the act of copying in the art world has never shaken off the derogatory remarks made about Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Andy Warhol. But artists and artisans have often justified using photocopies in their practice. As well as the aforementioned (provincial) fanzine culture of the 70s–90s we can point to more esoteric manifestations – such as the now defunct International Society of Copier Artists (I.S.C.A) and practitioners like Marilyn McCray and Patti Hill. Other high profile artists have dabbled with the medium, such as Yoshitomo Nara with his Floating World series.

Currently, there seems to be a revival among much younger cultural groups that are reinventing the practises round photocopying away from the confines of academic art and towards everyday relationships. This can be seen literally under my nose.

The place I work at, WORM, an avant-garde arts centre in Rotterdam, has slowly become a place that reinvestigates how paper as a medium, and copying in particular, can be used as a practice that crosses artistic, physical, sexual and socio-cultural boundaries. Our very own underground lending library, The WORM Pirate Bay, regularly hosts fanzine-making nights, including a special futurist fanzine workshop back in 2015 for the Netherlands’ first Afrofuturist festival, and safe spaces and activism hubs for queer zine makers.

This November (2019 CE), WORM hosts the 5th anniversary of Zine Camp, whose modus operandi “is to make zines and friends, giving space to the making of zines as much as to social interaction and collaboration with (un)like-minded people. This is embodied by the open workspaces that include free basic zine-making materials and copy machines for everyone to use. The workshops, zine stalls, talks and events are its tentacles, intertwined and bound together, like the changing string figures in a game of cat’s cradle.” Note the accent on physicality and togetherness and a wider creative commons replacing the trope of the solitary artist.

Questions around physically interacting with photocopiers are also part of the story, and can be expressed in surprising ways. In some ways it’s a shame that the party trope of taking a snap of one’s orifice in the office has overshadowed the potential of the machines themselves. They can be as temperamental as mules, invoking unlooked-for artistic reactions on the way.

Two examples spring to mind. The first involved a photocopier that had suddenly blinked its last blink in the Blade Factory at Liverpool Sound City. This unhappy lump of plastic, glass and metal was first wholly covered by the paper it contained, then forcibly trundled along an impromptu sacred landscape of debris and paper waste towards the neighbouring Liverpool Arts Lab’s day-long skiffle workshop. WORM Rotterdam met the ‘Pool’s Arts Lab head on in an intermittent, four-hour battle of percussion and groovy intonations with the copier repeatedly hit as part of a shamanistic purifying ritual.

The second involves Estonian producer and musician Mart Avi, who made photocopies for an installation on metallic mirror paper. “The first print-house I went to flat-out refused to print on these and later on I saw why. It was shooting out visible sparks when coming out from the printer, the operator got an electric shock and was pacing around in confusion – for this evening it seemed that the whole machinery had transformed into a diabolic paper-fuelled Tesla coil that is going to zap us out of existence. It came to a unified silver brick as static electricity made it difficult to separate the sheets, every attempt to do so induced a shock.” The electrostatic discharge created by the static build-up between the metallic coating and the surface in the printer it was pulled through created a memory of unnecessary pain for Mart’s art, a memory I may return to at some point, in a new set of photocopies…

Out of Toner

I am beginning to wonder if this urge to photocopy isn’t just a reflection on a comfortable state of stasis. Given the fact that I have boxes of copies filed away to be reused or chopped up, the feeling of taking one step back to take two steps forward is never far away. A form of procrastination dressed up as creation. Still, the act of copying also affords a feeling of the future – a physical take on using Instagram filters maybe – whilst having that tactile elements that links us to ourselves in a way that staring at a mobile screen never can.

Face to Face: The Museum of Photocopies opens at WORM Slash Gallery, Rotterdam, on 10 October