“If you look in back of the instruments, there’s like a table that’s sort of sticking out, can you see that?” Livia Polanyi is holding a small black and white photograph up to the inbuilt camera on her laptop. It depicts the room on the first floor of the Apollohuis where she and Remko Scha lived together from the end of the 1970s till the middle of the ‘80s. With its low ceilings and long, sparsely-furnished, open-plan design, a refurbished and domesticated ex-workspace in a former industrial building, the room I can see in the picture looks quite a lot like some of the loft-type spaces occupied by friends of mine today, in Hackney Wick or parts of South-East London. The table she’s showing me – a fairly small, unobtrusive, functional piece of furniture – was Scha’s work desk.

“I came home one night,” Polanyi continues, “and right in front of that desk there, Remko was there, and he was very happy and very excited. He had put a guitar down on the floor and hooked up a – I don’t know what it was – a fan motor? Something like that. And that was the birth of The Machines.”

From the beginning of the 1980s until his death in November of 2015, The Machines was Remko’s band, though he never struck a note on any of their instruments during the group’s lifetime. Not directly. Described on Scha’s website as “a group of electric motors who play electric guitars”, The Machines was an exercise in automated music, a hybrid of kinetic art and minimalist punk rock. Their first concert was in Eindhoven in 1980, acting as “guerilla support act” to goth rockers, Bauhaus. Over the years that followed they would play at art galleries and rock concerts throughout the United States and the Netherlands, sharing bills with the likes of Z’ev, Marina Abramovic, Tuxedo Moon, and 23 Skidoo.

Polanyi remembers one gig in particular, programmed by the Holland Festival and broadcast live on the Dutch public broadcaster VPRO, when the guitars caught fire in the middle of the show, great licks of flame curling up to the rafters of Amsterdam’s Carré theatre. “This was like the fucking Holland Festival!” she recalls. “Fucking television! Your thing blows up. And he was so delighted. Oh, look at that!” She squeals delightedly at the memory.

It was at New York’s TR3 in 1980, supporting Glenn Branca and Wharton Tiers, that Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth first saw The Machines. “I had never really heard or witnessed anything like this,” Moore recalls in an interview for Luuk Bouwman’s (2000) film, Huge Harry and the Institute of Artificial Art. “There was something really interesting and wonderful about seeing this guitar music without seeing some long-haired heavy metal guy taking up all the space.”

It all started that one night in the Apollohuis, just as Polanyi got in from her two-hour commute from the University of Amsterdam. He had a cheap fan motor with a shoelace attached and an electric guitar laid out on the floor. “He expected a boring ‘boing-boing-boing’,” Scha’s widow, Josien Laurier tells me. “But it went, ‘dum-dedumdum-dedum’. It was much more musical than he expected. Much more complex.”

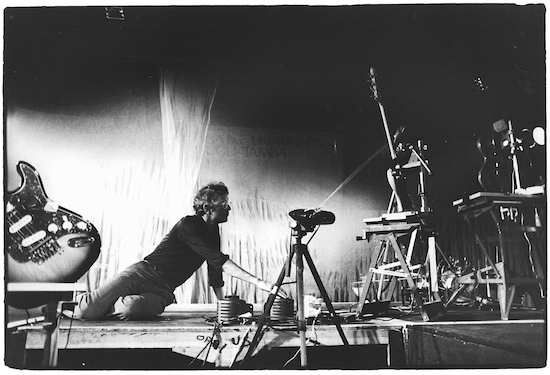

Remko Scha’s The Machines at ICA, London, 1983. Photo by Andrew Catlin

Born in 1945, Remko Jan Hendrik Scha grew up in a cultured milieu in Eindhoven. His parents “were up to date with music”, according to Laurier. “His father loved Stravinsky, they went on vacation to France and listened to French chansons, but also they listened to Stockhausen. On the visual art front, his parents took him to the Van Abbe Museum.” As he got older, Scha would visit Eindhoven’s 1930s contemporary art museum often, delighting, in particular, at works by the informel school of French painters, like Jean Fautrier and Jean Dubuffet, and COBRA artists like Asger Jorn and Karel Appel. “This was the beginning of his own art,” Laurier tells me. “He discovered that he liked the look of these artworks from very close by, that he liked the material.”

“At home,” she continues, “he burnt down a badminton shuttle and was astonished by the result.” Scha carried on doing what he would call Plastic Meltdowns from 1962 to 1992, melting records and radios, combs and toy soldiers, and sometimes strange, unidentifiable agglomerations of things that merge together in the heat of the oven into peculiar blobs and swirls of abstract colour. “He realised,” Laurier says, “that he had had this aesthetic experience, only he had had no hand in it. There was no virtuosity on his part – and still it was at least as good as the works in the museum.”

The Plastic Meltdowns were one of the first things that caught curator Tom Godfrey’s eye, glimpsed in a low-quality jpeg online somewhere some two and a half years ago. He had started searching for Scha’s name after a record by The Machines caught his eye in the mail order catalogue of an Amsterdam artist-run bookseller called Boekie Woekie. “I was googling around,” Godfrey recalls, “and I think I saw some really bad jpegs of the Album Pages and some bad images of the Plastic Meltdowns and I just had a sort of hunch that there was some really good stuff in all of this.” Godfrey’s Nottingham gallery, TG, opened their show of Remko Scha’s visual work at the end of April. “I think it was the combination of the works on paper, the sculptures, the machine guitars, then finding out this scientific stuff which, you know, I am only really starting to get my head around some of it. Then I just go in touch with him.”

Remko Scha, Remko Scha, Plastic Meltdowns (1-84), 1962 – 1992, Courtesy Remko Scha and TG, Nottingham, Photo by Reece Straw

It was this “scientific stuff” that had brought Scha and Polanyi together, forty years ago. “The first time I saw Remko,” Polanyi recalls, “he was giving a talk in Boston, at the Association for Computational Linguistics, about PHLIQA.” Built in the mid-70s by Scha and his colleague at Philips research lab, Jan Landsbergen, PHLIQA was a natural language processing machine – a computer that could answer questions put to it in plain English, ancestor of sorts to today’s software assistant AIs, like Siri and Alexa. “It was an absolutely brilliant system,” Polanyi says. “Probably the only one at the time that actually really addressed parsing sentences, interpreting them semantically, and then interpreting them relative to a world model. I fell in love with him, when he was giving this talk.” Two years later, she moved into the nascent Apollohuis, just shortly before the beginning of its public programme.

A former cigar factory on the east side of Eindhoven’s central ring, the Apollohuis would become one of the most important venues in the Netherlands’ bustling network of alternative cultural spaces in the 80s and 90s. It was started by Scha and composer Paul Panhuysen as a site for the manufacturing of “situations”. “Remko wanted a space where he could make big installations, and this former factory was for sale,” Laurier says. “Paul shared Remko’s belief that the end of art was there, and that the next step was simply creating a party.”

The Apollohius was certainly a party. On the corner at the border between two districts of the city, with Tongelresestraat, a working class street leading off on one side, and the solidly middle class Valklaan on the other, the Apollohuis was also a meeting place in another sense: between different factions, different communities, different worlds. A place where Eindhoven’s high-culture museum crowd could rub up against what Polanyi recalls as the “green-haired, emaciated kids with god knows what hardware inserted wherever”. It was a place where installations by John Latham and lectures by Dan Graham might sit side by side with gigs by Julius Eastman, Steve Beresford, Derek Bailey, and Phil Niblock. Polanyi vividly recalls the day the Kitchen tour came to the venue, featuring Robert Longo, George Lewis, Rhys Chatham, and the dancers Molissa Fenley and Bill T. Jones. “That was just astounding,” she remembers. Ellen Fullman’s first Long String Instrument album was recorded there. Akio Suzuki’s Soundsphere, also. As well as several records by The Machines and Scha and Panhuysen’s collaborative improvisation group, The Maciunas Ensemble.

The Maciunas Ensemble – Scha, Panhuysen, Hans Schuurman, Leon van Noorden, and Jan Van Riet, plus, later, whoever happened to be around at the time – “met every Thursday ten years and improvised music together,” Polanyi recalls, “which Remko would then record on a giant Ampex tape recorder. Then they would discuss exactly what happened. Then when people would come, there were all kinds of instruments, and different people played these different instruments. Most of them played but they did not, in that sense, know how to play. The whole idea of the Maciunas Ensemble’s improvisation was listening, actually. It was exactly not jazz. I eventually built a theory of conversational topic shift which was very much influenced by that.”

This kind of free flow of ideas between art and science was characteristic of Scha and Polanyi’s life together – and of Scha’s life all over. “He would have a happening one night and the next morning, with his sleepy head, he did experiments about sound perception,” Laurier says. “He wanted his art to be science and vice versa.” She met Scha in 1997 at the launch of a literary magazine she was editing. “We talked,” she tells me, “and for the rest of the evening I neglected all others, because I thought: finally someone who understands.” Going back to his place, a short while later, she remembers, “his guitar installation was on one huge wall, ready to play. There were many computers and uncountable books and vinyls and piles of papers. Also, one of those first nights, there was a young man, a typical nerd, working on a version of Artificial. I think at the time he had no home, and stayed therefore with Remko. Also there was a huge dead cactus.”

Remko Scha’s The Machines at ICA, London, 1983. Photo by Andrew Catlin

Artificial, in a sense, may have been the greatest culmination of Scha’s crossover between the worlds of physics and contemporary art. First developed on an Apple Mac at the very beginning of the 1990s, it follows on from experiments Scha did in the 80s where he would set his Machine guitars to work drawing pictures instead of making noise. Artificial goes much further. Using what Scha called a “visual grammar”, the software is capable of generating a never-ending, never-repeating series of graphic imagery. Its virtuosity is practically limitless. Just watching it for a few moments at the gallery in Nottingham, I saw it produce wild cartoonish flower petals in bright orange which then morphed into something like a cut scene from Space Invaders, and then towering, distorted letters writing spontaneous sound poetry. I’ve seen other screen grabs that even more hallucinatory images: bands of interlocking metal teeth, cascades of iron filings in purple and blue, virtual geometries shimmering like liquid. “Artificial itself is a parody,” Laurier tells me, “the last parody. The idea of the last work of art, the work of art that has it all.” The possibilities, quite literally, are endless.

“He was always making something else to make the work,” Godfrey says. “So it was a computer program that could generate imagery. It was a domestic oven that could make the sculptures. It was machines that make music. It was all part of the same thing.” As Laurier herself says of the Machines, much the same could be said of almost Scha’s projects, “he just wanted to set up the ideal circumstances for the phenomena to manifest themselves, for the process to happen. A good composer, he said, is himself a sort of natural phenomenon.”

“The last time I saw him, I was in Amsterdam, and it was fantastic weather.” Polanyi and I had been talking for the best part of an hour by this point and it’s clear that she’s enjoying reliving some of her memories with Remko. “And the thing is in Amsterdam, whenever it gets to be sunny, everybody leaves. Half the stores are closed. So Remko and I just walked and talked for an entire week. I remember him saying, open your eyes, and look. Just look through your eyes. No artist has ever been able to create an image as complex as what you see in the world everyday.”

Remko Scha is at TG Gallery, Nottingham, until 4 June 2017. A special performance by The Machines will take place at Nottingham Contemporary on Saturday 3 June