In spite of travelling around the globe, Raymond Depardon’s principal concern is not really one of travel, adventuring or globe-trotting. Instead, the seventy-five year old photographer’s work seems to dwell upon people and communities who are in the opposite of situations. Entrapment of various sorts – social, political, even physical – is the overriding theme of his work, or at least the work on show at Traverser, the current retrospective at the Henri Cartier-Bresson institute in Paris.

The traverser of the exhibition’s title can only be a reference to the photographer, the scope of whose travels is as vastly infinite as the ensnarement of the many people whose faces and bodies make up his compositions. But there’s something intangible in the honesty of Depardon’s images which allows him to blend in with the walls, landscapes and institutes; where he is no longer the traversing outsider but sufficiently part of the fabric to capture people with seemingly no distancing effects at all.

Though incredibly well-known as both a photographer and a filmmaker in France and Europe generally, Depardon is perhaps most famous in Britain for his series of photos of Glasgow and they are undoubtedly one of a number of a high-points in his work. Taken in 1980, they define the country and the decade that would follow: the enforced collapse of industrial areas whose whole infrastructure was decimated by the move towards the financialisation of cities, with the occupants faced with little choice but to carry on with life in the remaining ruins. Depardon’s photos explicitly show the continuation of life – a surprising sense of optimism present in spite of the constant palette of rain-sodden concrete and the grey glass of smashed windows – as a city literally falls.

From seeing images of the series not featured in the exhibition, however, this optimism is a misnomer, as other photos show a great and hopeless deprivation. One photo shows an elderly man and woman waiting with their backs to the camera at a bus stop. The street could be in the middle of a war zone, with the building opposite looking as if standing in the aftermath of a bombing raid. But they continue with the routine of living all the same.

This sense of ruinous space also builds as a theme as Depardon goes into war zones proper, both before and after the Glasgow series. Though this is marked in much earlier work, the most effective are images from more recent conflicts which bear all of the recognisable hallmarks of rolling news imagery but with a sense of humanity reinstated. A series of his photos from Beirut during the last months of the Lebanese civil war are the most effective. In the majority, he chooses to show the spaces left by the decade and a half of bombing and fighting; rooms missing walls that look out onto debris-strewn streets, chairs in the corner of rubble that were once homes sitting in strange contrast to the total destruction all around. There’s a sense of resistance to the typical imagery of war on the whole. It is the people and spaces stuck within conflict that take precedence rather than the conflict itself.

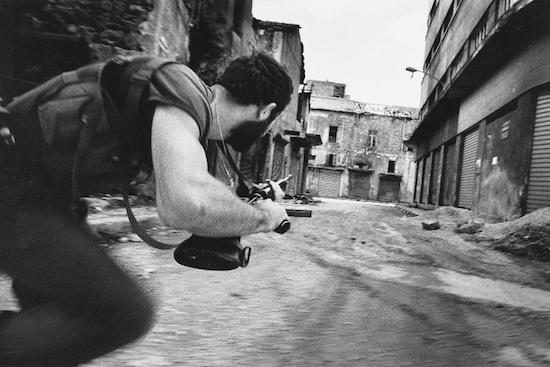

This is not to say that the photographer isn’t adept at that type of photograph. From the same shoot, a photo dives straight into the action of guerrilla warfare, getting so close to the perspective of a moving soldier that it feels almost like a still from a video-game. The blur, the almost unreal motion captured, is astounding as the soldier runs across a street, covering potential fire from more broken windows. The Beirut solider is an exception to the photographer’s sensibilities on show, however. More typical are his pictures from Vietnam collected in the series Adieu Saigon, the most powerful of which shows various young men now blinded and walking in the street. The image has a quiet brutality, the young men now forced to continue life without sight, on the verge of bumping into each other and old before their time.

The exhibition is filled with individuals in similar situations housed in walls, literal and figurative: the walls of war, poverty, mental institutes and prisons. If the exhibition was to be summarised by one image, it would be Depardon’s picture of an inmate at the Maison Centrale de Clairvaux. The inmate is jogging, the route so defined and worn down on the grass as to now be a bare circle in the grass. The man’s journey is endless, a security mesh hanging above him as he runs on.

Depardon captures institutes with a rare eye; the faces he captures already showing the signs of a different sort of capture beyond language. Throughout the exhibition, the words of Michel Foucault repeatedly came to mind. He writes aptly of the act of exercise itself that it is “the technique by which one imposes on the body tasks that are both repetitive and different, but always graduated. By bending behaviour towards a terminal state, exercise makes possible a perpetual characterization of the individual…”. With the difference taken away, what does this exercise become?

The photo is one of the most disturbing of his images because of how constrained this flexing of individual character is; the route always defined and shared, the mind now locked doubly into both the physical behaviour and the unchanging scenario around the man. Considering in hindsight the pleasure this small task probably produced away from the man’s cramped cell grounds the viewer further in a stark realisation.

One of Foucault’s most famous dictums comes from the same volume as that quote, Discipline and Punishment (1975), where he writes that “Surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it is discontinuous in its action.” The idea being that the main role of surveillance is change of behaviour rather than documentation for social safety. I repeatedly thought of Depardon’s eye, a different form of surveillance – momentary, desiring to capture behaviour rather than to dictate it – travelling around the globe to apprehend those trapped in what can only be described as an array of stases.

What Depardon’s photography does, quite miraculously, is bypass his presence as a distanced surveyor and seemingly liberates his subjects – albeit briefly – through sheer acknowledgement. This is counter to the basic intuition of an outsider documenting others but it seems to work because his eye is so roaming, because he is such a traverser, unburdened enough by systems of his own to capture those trapped within them, creating the most poignant of damning visual critiques. It is for this reason that he is still undoubtedly one of the most important European post-war photographers still working today.

Raymond Depardon: Traverser is open at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, until 24 December