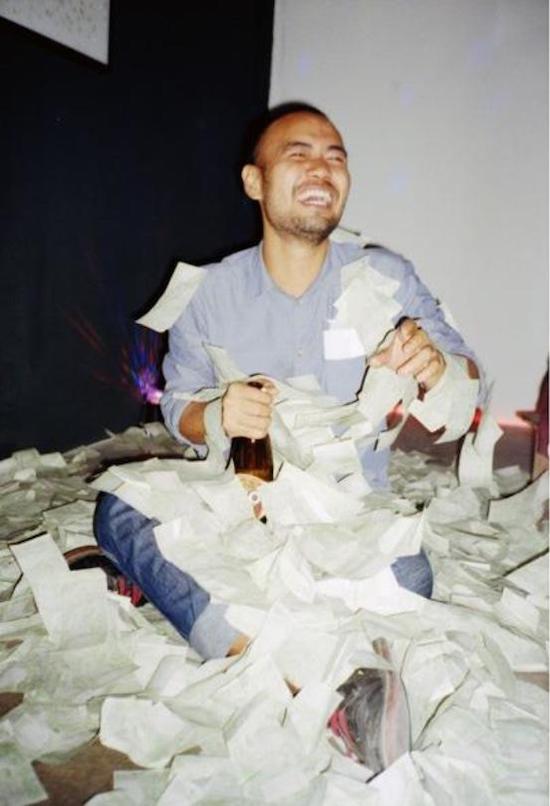

Portrait courtesy General View Records 場.景.設.定

On the third day of Pisitakun Kuantalaeng’s show, Black Country, the mood was jubilant. The 72-hour multimedia installation at Thong Lor Art Space had almost finished without incident, and attendees were congregating outside the building in the hot Bangkok air, smoking and drinking coffee. Then, Pisitakun glanced inside the gallery, and noticed two unfamiliar men. “Oh fuck,” he thought. “It’s the police.”

In Thailand, a visit from the cops can herald the beginning of a nightmarish journey through the military courts. The strict laws which straightjacket freedom of speech have been in place since the early 1900s, but have been enforced with increasing harshness since the military overthrew the Thai government in a 2014 coup. The country’s infamous lèse-majesté law, called Article 112, can inflict a prison sentence from 3 to 15 years for each count of insulting the Thai monarchy. Sedition charges are also on the rise, and speaking out against the ruling junta can also result in jail time.

The gamut of punishable lèse-majesté offences runs all the way from the tragic to the absurd. People have been charged for writing a play about an imaginary king; writing anti-monarchy graffiti on a bathroom stall; and wearing black on the King’s birthday. The much-loved King Bhumibol Adulyadej died in 2016, and was succeeded by his son, King Maha Vajiralongkorn, known for his colourful personal life. After photos of King Vajiralongkorn walking through a German mall in a skimpy yellow crop top began doing the rounds on the internet last year, the Thai government announced that even looking at an anti-monarchy image online could result in punishment. Seeing, however, is not prerequisite for being arrested; in January, a blind woman was sentenced to 18 months in jail for sharing an article on Facebook deemed defamatory to the king.

It’s not surprising that 31-year-old Pisitakun was worried when he spotted the police at his show. Black Country began in 2016, as Pisitakun watched the bickering between Thai political groups. “People don’t want to listen to each other,” he says, “They’re just angry with the corruption. That’s when I really wanted to express something that didn’t allow for dialogue. Not something that was a step-by-step negotiation – something noisy.” The result was his first album, also called Black Country, where pounding techno and ear-scraping distortion batter audio samples of military generals announcing they have seized control of the country. The timing was almost prophetic. Shortly after Pisitakun had finished up the concept and artwork, the revered King Bhumibol Adulyadej died. The country was plunged into deep mourning; everybody wore black clothing for a year.

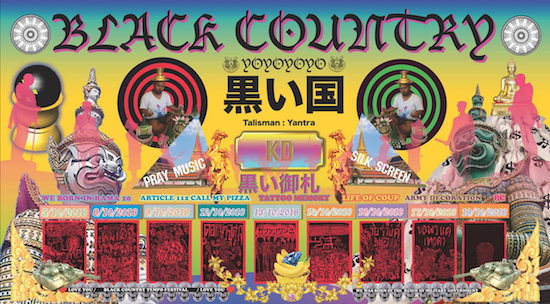

Pisitakun put on Black Country as a multimedia show a year later; he studied fine art at King Mongkut university, and visual and performance elements feed into his music. The show had been a three-day, non-stop parade of musical improvisation, film screenings and poetry recitals designed to test Thailand’s silence. With a clownishly provocateur spirit, the event poster featured a distorted photo of Pisitakun topless and holding his chest like a glamour model. The poster’s silliness matches the deeply farcical nature of the censorship laws; a slogan read “Article 112 Call My Pizza”, referring to the local pizza delivery company with a near-identical phone number to the lèse-majesté law.

The police approached him and asked what the event was about. He told them the show was about Japan, not Thailand, and they left, but more officers kept appearing. “They took three paintings, about 20 silkscreen prints and all the posters that I used,” he says. When he protested, the police told him that if the artworks were as innocent as he had told them, he could come and collect them from the station in a few days’ time. He still hasn’t got his work back, worried that another confrontation would be pushing his luck. He had to close the show early, and cancel three upcoming performances he had planned.

Gallery raids in Bangkok are not unknown. In June last year, the police wandered into Ver Gallery, seizing three photos from Harit Srikhao’s show Whitewash, which explicitly referenced the crackdown on the 2010 Thai political demonstrations in which over 90 protesters died. Mit Jai Inn, an artist and friend of Pisitakun’s who runs the collective Cartel Artspace, says that the junta still visits Cartel and three neighbouring galleries every month, looking for infractions against the military’s culture of censorship.

Yet they remain mystified by political art if the message is hidden behind any kind of symbolism. In June, the artist Paphonsak La-or exhibited a series of kitsch, postcard-style landscape paintings of every country harbouring a Thai political exile. On visiting the gallery, the junta admired the pastoral, realistic images. “They saw a landscape painting show,” says Mit. “They didn’t understand what’s behind it. They said: ‘Oh, what beautiful landscapes!’” Mindful of contemporary art’s potential to confuse, he tells young artists to respond to military questioning with “sophisticated terms about art and philosophy. I tell them to put in a lot of English – even if they don’t know what it means.”

Pisitakun knows the consequences of being too direct. In 2012, he staged a controversial piece of performance art which had a clear-cut message and literal imagery. He says news of the performance started to spread on social media, and friends told him he needed to get away. He left Bangkok for Indonesia and then Japan, returning to Bangkok in 2013. Since then he’s adopted Mit’s get-out clause of playful obfuscation, necessary for the climate of severely restricted speech, feeling out the limits of Thailand’s cultural taboos and finding joy and humour in evasion. This strategy paid off in his personal life too. A military draft conscripts Thai men into service using a lottery system. When his name was called, Pisitakun dodged the draft by putting on 45 kilos before his medical exam, and falling over during the exercise test.

Having started out as a visual artist in Mit’s circle, he turned to music in 2015 as another tool for indirect expression. He was inspired by the European techno scene: “When I went to Berlin – and it was the drugs as well – the sound makes me feel really different from visual art. It talks to your brain in a different way. Music isn’t as direct as an image. If you make a picture of a sacred image and cut it, it’s dangerous: people know right away when they see it. But for sound you can cut it and mix it and people don’t know. It’s more of a game.” In noise and experimental music, he’s found tools similar to the indirect speech that Mit had shown him in the visual art world. “Abstract art and noise music protest in a different way,” says Pisitakun, “You need to find a way to play with them.”

Black Country also draws on black metal. “That music is about Christianity, but I adapted it to talk about Thai issues. They have lyrics, but you can’t understand them because of the singing style. It’s really nice for me to use this way to criticise something. You can get away with saying more. You have to listen hard.” He loves metal’s double bass drums and blistering fury: “It gives you more energy to fight,” he says. “We are a very relaxed country; a smiling country. But it doesnt mean were happy all the time, we just keep it inside. Sometimes it’s propaganda when it says we’re good, calm people, and we don’t need to fight. We’ve had many protests where people were killed by the government. Only propaganda could say to the world that we are smiling country.”

Early this year, Pisitakun’s father died of cancer. As is Thai tradition, he shaved off his bushy beard and got ordained, spending a day and a night as a monk to make good merit for his father’s spirit. His next album will be about this experience, mixing in Thai funeral instruments, like the sweet-toned Ching bell and the wooden pipe known as a Khlui, into his electronic soundscapes. He recorded his father’s final moments for the record; laboured breathing, the sound of a heart monitor, as well as the monks’ funeral chants. “It feels really sad but it gives me energy,” he says. It’s a chance to speak directly, without games.

Portrait by Graham Meyer

Still, in a world where monks fly on private jets with Louis Vuitton luggage, he is far from idolising Thai Buddhism as an institution. “Being a monk is good money,” he says. “When you go and pray you get 300 baht [about £7] even though you have no living expenses, and you can go four times a day. Too many monks in Thailand do it to get rich. If you become a monk for three months you have enough money for a scooter.”

The Thai military government says it will hold its first election for eight years next February, and although Pisitakun knows it’s unlikely to be a fair fight, he feels it’s a step towards a country with more freedom of speech. Until then, noise music provides him with strategies for expressing ideas and feelings which would otherwise be too dangerous to utter.

Pisitakun is currently touring Europe, playing his London show at Cafe Oto on Sunday. He is featured on the forthcoming split EP Dângrêk Mountains with Lafidki and Ayankoko released via Chinabot on 9 March