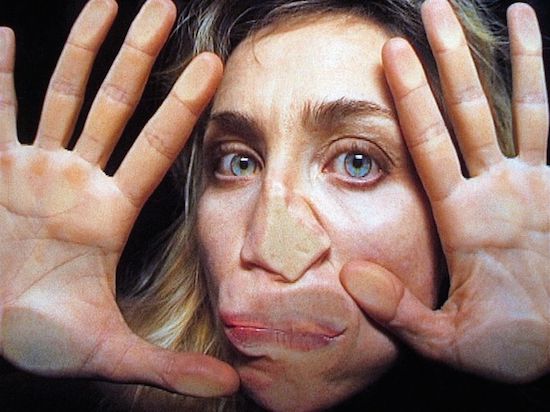

Pipilotti Rist, Open My Glade (Flatten), 2000. Single channel video installation, silent, (video still)

© Pipilotti Rist. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine

In the Danish suburb of Humlebæk, half an hour by train from Copenhagen. stands the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, a discreetly modernistic building blending into the landscape of what used to be an old manor house. The journey from the station takes a further ten minutes, a sedate walk along suburban streets that could almost be anywhere. I had caught the sleeper train in from Stockholm the night before, arriving in Copenhagen this morning. The reason for my journey was the exhibition at Louisiana of the works of the Swiss installation artist Pipilotti Rist.

I arrive shortly before opening time, and there is already a small queue at the door. A light rain starts to fall.

For those unfamiliar with Rist, a somewhat unreliable yet illustrative capsule summary may be to imagine Björk had she gone into video art rather than pop music. There is the same sense of polychromatic, psychedelic playfulness about her work, of embodiment rather than detachment leading into both a rich sensuality and a pronounced feminist sensibility.

Rist, born in 1962, began her artistic career in the early 1980s. She started making single-channel videos influenced by the then-ascendant music video format, and branched into video installation: art objects with embedded screens and projectors, displaying purpose-made video loops. Her more recent works have been more expansive, not so much videos or objects but installations in spaces.

Context matters in her work, with most of it being impossible to experience outside of an installation. As such, any exhibition of Rist’s work is going to be in part a retrospective, and this one was no different.

Pipilotti Rist, Installation view from ‘Pipilotti Rist Sip My Ocean’ Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia, 2018 © Pipilotti Rist. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine

Photo: Jessica Maurer

A significant proportion of Louisiana’s sprawling space, in several rooms on two levels, has been dedicated to the the exhibition. One enters through a long corridor lined with images of video screens, and is met by a screen showing the artist pressing her face into glass: her nose and lips forming flat polygons against the screen, her pale blue eyes locking expressionlessly onto the viewer as she contorts against the screen. In a subsequent shot, she wears red lipstick and bright green eyeshadow, which leave smears on the glass. This work, whose title Open My Glade the exhibition borrows, originally ran on an advertising billboard in New York in 2000.

This corridor opens to a room with two alcoves showing projections of Rist’s early videos, as well as a number of installations. Several videos play: feminist détournements of John Lennon, such as the glitchy, static-riven I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much(1986) and Sexy Sad I (1987), setting the nigh-eponymous Beatles song to footage of a naked man dancing among autumn leaves).

In other videos, Rist repeatedly faints and falls on a lawn, soundtracked by her punk band Les Reines Prochaines, she mimes along to a Kevin Coyne song over projection of video from a train window, and appears naked and covered with (stage, implicitly menstrual) blood, to a song by Swiss ska-punk band Sophisticated Boom Boom. A room to the side shows Rist’s (1997) work Ever Is Over All, in which the artist walks down a street carrying what looks like a large flower, swinging it, smashing the windows of parked cars and beaming with almost orgasmic glee – a video that almost certainly inspired Beyoncé’s ‘Hold Up’ some two decades later.

Another room shows Sip My Ocean (1996), a video based around a cover version of Chris Isaak’s ‘Wicked Game’. Rist and her musical collaborator Anders Guggisberg played the song straight, minor-key slide guitar with Rist’s vocals not unlike a Berlin cabaret singer. Rist then overdubbed a second vocal, accentuating the song’s emotional arc, screaming its lyrics over the mix.

Pipilotti Rist, I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much, 1994.Single channel video, colour and audio. (video still). Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Acquired with support from Museumsfonden af 7. december 1966 © Pipilotti Rist. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine

Other videos are embedded in objects: in Yoghurt On Skin(1995), Rist’s blinking eye – a recurring motif in her work – peers out of a viewfinder-sized screen embedded in a large seashell, and a crystal ball in a plush pink satin handbag shows waves, a speaker quietly playing a few bars of euphoric synthpop not that far from Erasure or New Order. Further along, a canary-yellow bathing suit hangs from the ceiling, its abdomen holding a spherical television, whose light plays through the fabric. The screen apparently shows video from an endoscopy camera, though only the corners protrude.

The room is dominated by Vorstadthirn (‘Suburb Brain’, 1999), a large diorama of a modernist suburban home. It is dusk there; the lights are on, and video projections on the gallery walls evoke the colours of sunset. The house’s garage conceals a video projector, which plays on its wall a home video of domestic life: a family sitting down to dinner; only, here, the food on their plates is all on fire.

The wall of the gallery is covered with a collage of white packaging. On it, a video is projected of Rist speaking about philosophy and her childhood home. It is filmed in a moving car, her speaking mouth in closeup in the foreground, against a backdrop of moving scenery in golden late-afternoon sunlight. Further in the gallery, a hole in a floor panel shows a small LCD screen, with a loop of Rist calling out from a pit of fiery lava.

Other works take up larger spaces. 4th Floor to Mildness(2016) is a large darkened room, in which beds are arranged, giving a view of two large screens shaped like blobs or bodies of water on the ceiling. Projected onto these is crisp, high-definition video filmed by Rist under the waters of a Swiss river. Ripples of sunlight break through the waters, deep green lily pads and fragments of rotting vegetation float past, over a post-rock soundtrack by Austrian multi-instrumentalist Soap&Skin (Anja Plaschg). The effect is at once beautiful and slightly unsettling; the experience, both immersive, and collective.

Beyond that (past a loop of I Couldn’t Agree With You More (1999), of the artist walking distractedly around a supermarket, videos of naked people in urban forests projected over her face) is Pixel Forest (2016), another darkened room through which a path leads through a forest of strings of lights: organic plastic forms containing colour-changing LEDs, glowing in various colours, and changing slowly and seemingly randomly. The effect is abstract: foregrounds and backgrounds of pure, saturated colour. The lights’ ever-undulating colours, it is explained in a wall text, come from the pixels of a video loop, a video one can never be far enough from the individual pixels to see, and whose content remains a mystery to those immersed in it – literally unable to see the forest for the trees.

Beyond the pixel forest, on the upper floor of the exhibition, is a large room populated with exhibits, arranged to convey the feeling of being in an apartment, and collectively titled At Home Behind Eyelids. Where Suburb Brain examined the domestic quotidian from outside, here we see it from within.

An infant’s cot – Das Kreiseln (‘The Little Circle’, 1993/2011) – contains a model of a virus, in which an embedded screen plays a video, hands caressing bodies. Dinner tables, fireplaces and beds serve as projection surfaces (the bed’s duvet, which visitors are invited to lay on, shows exploding star fields, and occasionally, a human form tumbling through space). Next to the bed stands Deine Raumkapsel (‘Your Space Capsule’, 2006), a packing crate containing a diorama of what looks like a student’s bedroom. At one corner, the floor is broken away jaggedly, revealing the black vastness of interstellar space. Barging in through the gap is the large grey cratered sphere of a moon, occupying that corner. A mirror slowly rotates, projecting a video loop around the walls of the room, accompanied by the sound of wind, an old music box and that old chirping electronic chatter sound effect once used to signify computers. The ensemble evokes that peculiar sense of at once solitude and connection to the sublime that is both domestic and nocturnal. On the wall hangs a painting of a Venetian canal scene, its sky replaced with a blank space onto which video is projected: hands handling food, petal-strewn lawns, other skies with cherry blossoms. On a shelf decorated with knickknacks stands a melted plastic globe, patched up with tape; “help i’ve cut myself” is printed on a scrap of paper patching a hole somewhere south of Madagascar. Electric light pours out of the cracks.

Further in the room, a lamp stands next to a sofa chair. In it is concealed a projector, which projects a video into the lap of whoever sits in the chair. Video projectors are concealed everywhere: under a chaise longue, in a collection of liquor bottles (using one as a screen), in a hole bored in a rock. A writing desk is covered with an assortment of objects. On it is a blank book titled “Collective Poem, Louisiana Humlebæk”, and a note addressed “Dear mammal”, inviting the visitor to add to it. Various exhibits have signs asking the visitor not to touch them; these have additional instructions, such as “think in colours“, “walk on tiptoe”, and “let the cat out of the bag”.

There is an element of subversive playfulness throughout Rist’s work. Her détournement of the music video format works on multiple levels, from its distinctly uncommercial content to glitching the medium itself, slowing down and speeding up and pushing the electronic medium to, its limits – and beyond. Hyper-saturating and distorting video’s colours and breaking the screens down to stripes of hyper-lush coral pink and indigo, conjuring a sort of PAL psychedelia.

Another thread running through Rist’s work is music. She grew up in the shadow of The Beatles, influenced by their late psychedelic period, and entered the art world through music video production, and the affective vocabulary of pop music is a key part of her works. In works that are not specifically music-centred, Rist uses background music for affect – sometimes her own, at other times from other artists. The music varies with the aesthetic, from the almost Kickstarter-video twee of Ever Is Over All (1997) to the shoegazey post-rock in some of her more abstract projections. (One could make a case that Rist’s use of changing playback speeds and deliberate video distortion in her music videos prefigures the hypnagogic aesthetics of vaporwave, if one were to stretch it.)

After one more pass back through the gallery, and a visit to the gift shop (there is no video for sale, though alongside the exhibition catalogue and posters, there are lens-cleaning cloths imprinted with stills), I walk out into the suburban daylight. Walking past the bungalows of Humlebæk, I feel the anticlimactic sensation of a comedown, having left behind an enchanted space and reemerging into the mundane. On my journey back, images from the exhibition float into my mind’s eye. Rist’s model modernist suburban house; the bedroom crumbling into interstellar space; ripples of sunlight on water, and of video distortion, bursts of vivid colour. Microcosms of subjective wonder exploding like supernovae in the intimate spaces of the mundane, like glades opening in a forest.

Pipilotti Rist, Open My Glade, is at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark, until 22 September 2019