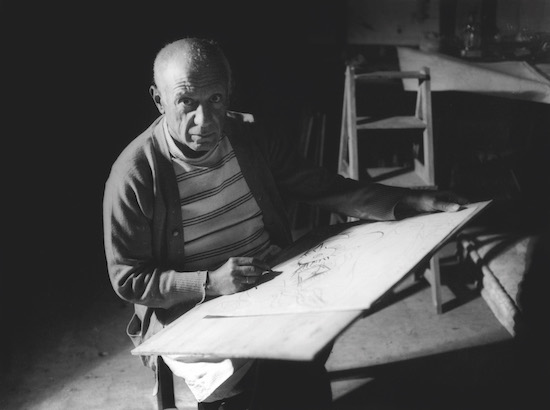

Pablo Picasso drawing in Antibes, summer 1946. Black-and-white photograph. Photo © Michel Sima / Bridgeman Images © Succession Picasso/DACS 2019

Picasso and the Minotaur; Picasso and the Portrait; Picasso and Printmaking; Picasso and Guitars; Picasso and Surrealism; Picasso and Collage; Picasso and Photography, even Picasso and the Ballet, and on and on. There are endless combinations of theme, genre, form to explore when it comes to this endlessly inventive, nimbly protean giant of twentieth century modernism. And since this exhibition is called Picasso and Paper, all of the above – and more – get a look-in.

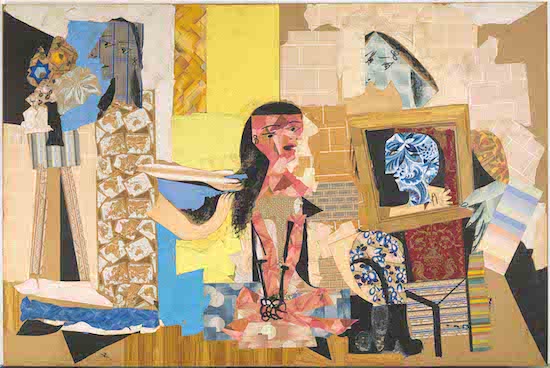

With the majority of its loans drawn from the Musée national Picasso-Paris, and spanning eight decades, this giant survey at the Royal Academy is – and I’m surprised I can say this, given there’s no shortage of ‘major Picasso surveys’ – uniquely revelatory. There are an abundance of ephemeral scraps, exquisite drawings and prints (he was among the twentieth century’s greatest printmakers), collages and collage-paintings, and collage-photograms in collaboration with photographer André Villers, 3D objects, painted studies, and a handful of finished paintings to anchor us through his evolutionary phases.

A room devoted to Picasso’s groundbreaking Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the 1907 painting that broke with his lyrical Rose period and heralded the arrival of Cubism, is filled with compositional studies and sketches of single totemic figures that show, for the first time in his work, the profound influence of African masks and carvings that he’d first encountered a year earlier when Matisse introduced him to a hand-sized Congolese figure that the older artist had recently purchased. And though the painting itself is represented by a projection, since getting it off the walls of MOMA isn’t a possibility, tireless workings and re-workings, which included, at one stage a medical student with a notebook and a sailor surrounded by the nude female figures, reveal much about the complex evolution of this major work.

Meanwhile, amid these rarely seen loans are the eight sketchbooks (one of which contains the intriguing study described above) dotted throughout the survey. They illustrate the development of other works, including the deeply poignant monochrome painting (and bronze sculpture), Man with a Sheep. Painted in 1943 during the dark years of the occupation of Paris, its religious connotations are clear, and there’s an almost palpable ache in some of these large ink and wash studies that’s quietly devastating.

Installation view of the ‘Picasso and Paper’ exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (25 January – 13 April 2020) Photo © David Parry/Royal Academy of Arts © Succession Picasso/DACS 2020. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London and the Cleveland Museum of Art in partnership with the Musée national Picasso-Paris

All of this gives the exhibition such a fresh twist and such a sense of emotional immediacy and intimacy; for rather than sticking to a presentation of discrete, finished works – which could still offer up new ways of thinking about the artist – this is an exhibition exploring Picasso’s creative process, which is uniquely rewarding. What makes it exciting is that we get a glimpse into the creative mind of an artist whose sheer joyful and infectious playfulness (even when the theme is sombre) and extraordinary invention is a highlight of every room.

The 1956 film, The Mystery of Picasso, by Henri-Georges Clouzot, captures much of the improvisational nature of this process. As he is preparing to paint with his inks on some newsprint paper, the reverse of which is being filmed, Picasso promises to surprise us. And this is exactly what he does – turning one creation into another, into another. And the final work is displayed in the gallery, as well as the stunning collage-drawing (using wallpaper cut-offs) of a reclining nude, also on film.

Picasso and Paper takes us from the artist aged around eight, with two tiny, fragile cut-outs of a dove and a dog, to the artist aged 90, wherein we observe a starkly anguished, bathetic self-portrait in black and white crayon, drawn in the penultimate year of Picasso’s life. The precocity is of course astounding. He could have been born with a pencil in his hand, and there’s a story that his first words were to demand a pencil. More plausibly, these are also said to have been his last, and he was indeed drawing to the end.

An academic study of a cast of the back of a male nude, drawn in charcoal and chalk when Picasso was 13, makes you marvel at the taut precision of his line. As do the series of drawings that immediately follow, executed some two decades later: two firmly outlined self-portraits, one in which the artist’s intense gaze rests on the viewer, keenly alert and vividly present, the other in which the elegantly attired artist is perched on a chair with a sketchpad balanced on a knee, scrutinising the middle distance, while the out of frame mirror that carries his reflection literally frames his figure in the drawn image.

Pablo Picasso, Femmes à leur toilette, Paris, winter 1937–38. Collage of cut-out wallpapers with gouache on paper pasted onto canvas, 299 x 448 cm. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Pablo Picasso Gift in Lieu, 1979. MP176. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Adrien Didierjean © Succession Picasso/DACS 2019

Nearby there’s a portrait, from a photograph that was taken by Picasso’s dealer Ambrose Vollard, of Renoir in arthritic old age, and here’s his first wife Olga Khokhlova, in exquisite outline with very little shading, as if she had been deftly traced. And here also is his famous, joyfully characterful portrait of Stravinsky, in which the composer’s prune-shaped head is dominated by the fussy bulges and creases of a heavy suit and his big, sausage-fingered hands.

Around the same period, a wonderful outline drawing of 1920, entitled The Artist’s Salon on Rue la Boétie, features Jean Cocteau, Olga, Erik Satie and Clive Bell, all elegantly lounging in an elegant, though somewhat compressed and fussily detailed drawing room that resembles a stage with the actors precariously balanced on chairs at the edge of it.

There are prints from his series of Vollard Suite etchings, commissioned by the aforementioned Ambrose Vollard and featuring the artist as an ancient Greek sage and as a priapic minotaur. There are the extraordinary Minotauromachy prints whose complex iconography and composition owes much to his later great war painting Guernica, whose evolution is also detailed here, and there are cut-outs of pedestrian objects – bulbs, cutlery, dancing figures, Dora Maar’s dog with its two eyes cut out by burning through the paper, and so on. And there’s a room devoted to his relationship to paper – the choices of paper that invited him to explore new ways of working, whether he tore it, cut it, drew on it, pasted it, painted on it, burnt it, printed on it, folded it to make free-standing objects, or scrunched it up and cast it in plaster cast. This is an exhibition that is so much more than what its simple title promises.

Picasso and Paper is at the Royal Academy until 13 April, 2020