Reclining Nude, 1932, oil paint on canvas, Private Collection © Succession Picasso / DACS London 2018

The year he settled in Paris. The year he was introduced to Matisse, whose enduring friendship was to spur the younger artist’s competitive instincts to even greater experimentation. The year he painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, having studied the African masks in the city’s ethnographic museum. The year he painted Guernica.

The years, in fact, that simply elide, since Picasso won’t and can’t be boxed into a single ‘pivotal’ year, for his style shifted and evolved at a frenetic pace. So much so that Jung, upon seeing Picasso’s retrospective in Zurich in 1932, declared that the then fifty-year-old artist had a mental disorder. But Jung wasn’t being dismissive: his irregular diagnosis of the artist’s “schizophrenia” was underpinned by his theories of the “Luciferian forces” of creativity. Still, Picasso’s admirers were not amused.

Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy is Tate Modern’s first exhibition devoted entirely to the artist, and it chooses the year in which Picasso had his first retrospective. Matisse, who was by then in his 60s, had been honoured with one the previous year in the same gallery, the Galeries Georges Petit in Paris, though it was still very unusual for living artists to have career retrospectives at that time.

Picasso was fifty, and by now revered and extremely successful. As well as retaining an apartment and studio in Paris he had purchased a big country house, the Château de Boisgeloup in Boisgeloup, Normandy, in June 1930, and was using his outhouse as his sculpture studio. It was in Boisgeloup where he entertained friends in the bosom of his family. But it was also where he could spend time alone with Marie-Thérèse Walter, the young lover he’d met on a street in Paris when she was seventeen, he forty-five, when his wife Olga and their son Paulo were back in the city. A recently acquired Hispano-Suiza limousine, complete with chauffeur, inspired his friend, the avant-garde poet Max Jacob, to describe this period as Picasso’s “duchess years”.

How far he’d come from the bohemian poverty of his Montmartre years, when he’d met the established and respectably besuited Matisse, and where he’d started out painting on cardboard because he’d had no money for canvas. And perhaps Picasso was now just a little concerned that the haut bourgeois life could indeed dull the edges of an avant-garde artist, enough to prompt him to jest, perhaps a little defensively, that “I’d like to live as a poor man with lots of money.” Despite all the trappings – or perhaps because of them – he was anxious to be seen as an artist who wasn’t standing still, for the art of the twentieth century, with him surely at its pinnacle, never stood still. And he was certainly anxious about getting left behind.

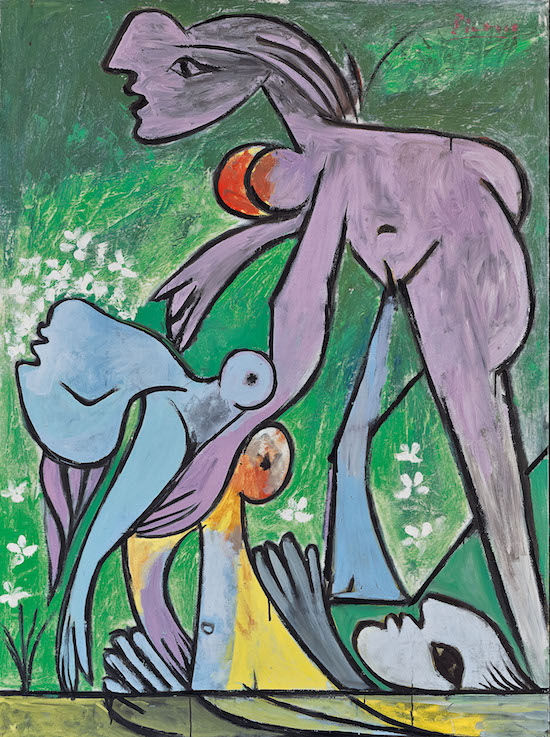

The Rescue, 1932, Oil paint on canvas, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler © Succession Picasso / DACS London 2018

Since he insisted on retaining absolute control, Picasso was given carte blanche to curate the coming retrospective that would open in June, and that would later travel to Zurich. When asked how he would do it, he replied, “badly”. He was giving nothing away. In preparation, he worked at a feverish pace to produce new work, just as he had at nineteen when he was given his first exhibition in Paris.

Tate’s exhibition leads us through this “year of wonders” month by month, partially recreating at its centre the Galeries Georges Petit retrospective, in which canvases are hung two deep on dark red walls, their chronologies mixed up and works left unlabelled. They include an exquisite classical portrait of Olga, a rugged self-portrait from his first year in Paris, a work painted at the height of his Cubist years with Braque, a pink-cheeked Paulo dressed as a harlequin, Paulo as a gimlet-eyed baby, and the Tate’s own darkly imagined, surreally disturbing Three Dancers.

But the work of 1932 focused largely on Marie-Thérèse, the girl whose classical profile had arrested Picasso’s gaze outside the Galeries Lafayette department store in 1927. Never before had Picasso painted portraits of such voluptuous sensuality, colourful exuberance and playful eroticism. And he greatly enjoyed playing perceptual tricks. With her head resting on her shoulder and a sweetly innocent smile playing on her lips as she sleeps, The Dream shows the top part of his lover’s bisected face as an erect penis, while her hands form an opening at her pubis.

Bust of a Woman, 1931, Cement, Musée National Picasso, © Succession Picasso / DACS London 2018

But there are intimations of violence, too. In a portrait echoing The Dream, Sleeping Woman by a Mirror, Marie-Thèrése looks not asleep but dead. The bisected face is now a jagged, gaping wound which looks like its been slashed open with a knife. A red slick of paint doesn’t so much denote her lips but suggests blood. Her one visible eye is a blackened hollow, while the colour scheme is cooler, a clash of acid hues, not the softer, brighter, happier colours of The Dream. Only in the reflection of her profile in the mirror, a white, ghostly outline, do we find the rounded dimensions of her innocently sleeping face.

Other paintings show her drowning and being rescued, or reclining with curling octopus limps, or once again sleeping or in luxurious repose. But the masterpiece of the show has to be Reading, and this time Marie-Thérèse’s face is a big, elegantly bisected heart painted in soft lilac and pale mint green, with the length of her nose a glacial white. He has painted her with the long side eyes of an ancient Egyptian queen. A sense of her soft, child-like vulnerability has been replaced by something steelier, coolly majestic.

The Dream, 1932, Private Collection, © Succession Picasso / DACS London 2018

There are sculpted heads too. One in bronze shows a fleshy, tumescent phallic nose hanging over a bulbous, heart-shaped face. It’s cute, dumb and animal-like. He was obsessed with that nose, that profile, and each distortion projects a different facet of how she was perceived by him.

We learn from the catalogue that Picasso spent the opening of his retrospective in the cinema, and then he was quick to get back to work, to not rest on his laurels. And so he retreated to Boisgeloup, this time to concentrate on smaller works. He produced a series of wonderful ink drawings riffing on Grünewald’s gory crucifixion, and a series of small, quick and loosely executed paintings of an Arcadian scene featuring a flute player and companion, these suggesting that he had the Manet exhibition earlier that year in mind and specifically Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe.

Picasso was nothing if not unstoppably prolific, but this was the year in which his creativity went into intense overdrive, and he produced some of the most compellingly erotic work of his life. Tate has managed some incredible loans and this is likely to be one of the most exciting Picasso exhibitions you’ll see in a long while.

Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy is at Tate Modern until 9 September, 2018