Paula Rego does not believe in making proper ‘Art.’ She says “if you are trying to be correct and do proper ‘Art’ or what you think is proper art you are constrained. You don’t play… and playing is the most important thing of all”. Unconstrained imagination and the ability to forgo notions of what “Art” is or should be characterises her work. This is perhaps why she is so comfortable with illustrating stories, an activity often disregarded by the art community. I went to see the exhibition Folktales and Fairy Tales at Casa das Histórias to find out what makes Paula Rego’s “illustrations” so unique.

Going to Casa das Histórias is like falling down a rabbit hole. You are transported into another realm, not just because Paula Rego’s work is fantastical. But its location outside the city forces you to go on an “adventure”, much like the protagonists of the stories she illustrates. I had this feeling as I took the train from Lisbon to Cascais on a rainy day. The ambience was perfect: the dark clouds rolling in from the Atlantic Ocean were ominous and spelled the beginning of my descent into this fantastical world.

As I approached the museum, I began to make out its dramatic shape. The building, designed by the architect Eduardo Souto Moura, has two imposing pyramids that announce the importance of the public space. Its red-coloured cement contrasts with the surrounding trees and freshly mowed grass. Inviting you to admire the interplay of natural and monolith. In all, the building looks like a house from a fantastical tale, the castle of a menacing king or the palace of a wizard. So in a way, it wasn’t surprising to read Souto Moura’s explanation of the two pyramids as influenced by Alcobaça Monastery and Sintra Palace. Once you step in through the small grout-like door and see the first room of the exhibition with Gustave Doré’s eerie illustrations your journey down this rabbit hole is complete.

The exhibition highlights the inherent interest Rego has in folk stories. Starting in early childhood, she was interested in the traditional tales her grandparents told her (they raised her until the age two). Once Rego could read, she looked through the classic children books on her own. It was also in her childhood Rego first showed an interest in disfiguration and mutation, she recalls cutting the fingers from a brand new doll. Though children often do such things (cutting hair comes to mind as classic childhood experience), she seems to identify this as a pivotal point in her childhood.

The first part of the exhibition features some of her early work including The Exile (Old Exile Dreaming of his Youth), which she painted in 1963. A tribute to her grandfather who was a Republican, as well as her father; both opposed the fascist regime. Rego’s illustrations of Brancaflor (1974), initially intended for a Jonathan Cape book about Portuguese stories, are also in included in this section. As well as the dolls she made with fabric, wool and other mixed media. The origin of Rego’s interest in stories is well documented in the first two rooms of the exhibition.

Paula Rego is fascinated by folk stories and fables because they “show human nature as it is, without being corrupted by the idea of ‘how it should be’ or any sentimentality.” Traditional stories tap into the unconscious of groups of people and are often interpreted psychoanalytically, just like dreams. Rego herself was interested in Jungian theorists. In her 1976 research proposal for the Gulbenkian Foundation, she expressed an interest in the “collective unconscious”. That is, in what makes some tales cross-cultural and part of humanity’s collective imaginary. Perhaps, this is the reason Rego adopts darker interpretations of didactic stories parents tell their children. She attempts to examine human nature, our shared fears and aggression.

Her illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood (2003) are an example of this. Just like Susan Brownmiller and other feminists, Rego interprets the story as a description of rape. The Wolf is represented as a predatory man in a tenebrous dark woodland. The third illustration, The Wolf Chats Up Red Riding Hood, shows the Wolf sitting across Red Riding Hood. Rego captures the duality of the Wolf: he appears dressed in women’s clothes with his arms folded, in a pose which could be construed as coy. Yet his stature (he is twice the size of the girl) and predatory gaze indicate a darker intent. This duality can be interpreted as representing the conscious and the unconscious. Across from him, the girl crosses her arms unreceptive to his advances. In the fourth picture, Mother Takes Revenge, it becomes clear the girl has been raped. The mother’s dress is red suggesting she has been consumed by her intent to seek vengeance, she is metaphorically covered in the wolf’s blood. Rego has said that in her paintings she puts women in difficult situations, or as she says herself, “in dire straits” to see if they can get escape. If they do she interested in whether they can get revenge, this is clear in her interpretation of this tale.

Although Paula Rego’s relationship to storytelling is innate and instinctive, her work is indebted to the research she did in 1976. At the exhibition, you can see the meticulous and thorough reports she did for the Foundation. They reveal more than just pure talent goes into her work. Highlighting the importance of this kind of work is as relevant as the exhibiting the pictures. She catalogued a list of illustrators and the stories they illustrated which interested her. The result is a visually pleasing report, an attractive mix of text, collage, and original sketches. This gave me another image of Paula Rego as a researcher working late nights at the library and not just as the painter in studio.

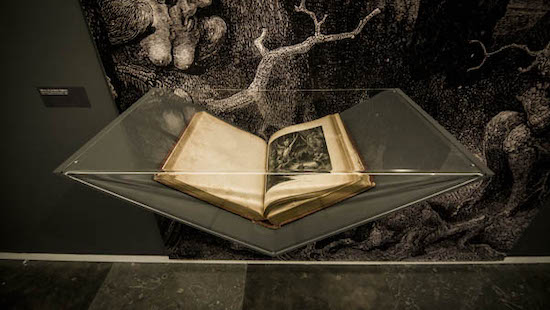

One of the highlights of the exhibition is the series King Pig (2006), it is a remarkable group of images and it reveals Rego’s dedication to the history of folktales. The story is from the Pleasant Nights by Giovanni Francesco Straparola, a book first published in circa 1551 often considered the first book of its kind. The story is about a prince born in the shape of a pig. When he comes of age, he wants a wife, so his mother finds a poor family whose eldest daughter agrees to marry him. However, on their nuptial night, the girl rejects him, and the pig kills her. The same happens to the family’s second daughter. Finally, his third fiancee accepts him and his advances, and the pig turns out to be a handsome man.

Rego’s treatment of this story is masterful, the bestiality of the pig and the dread of the girls is transparent in her compositions. Prince Pig and his First Bride encapsulates the disturbing story. The girl is depicted at the moment of her death, her eyes are rolled, and she seems limp. Although there is a sense she still might breathe, the small wound next to the pig’s hoof suggests otherwise. Rego adds another layer of intensity in suggesting perhaps the pig is not just atop the girl to kill her, but also to rape her. In which case, the eyes are rolled upwards so she can look away from what is happening. The result is a disturbing scene whose content contradicts the magical and lively colours Rego uses to depict it. Another contrast that can be interpreted as enacting the duality of the conscious and unconscious.

After going to the Folktales and Fairy Tales exhibition, I felt frankly overwhelmed. There are at least fifteen different stories and books mentioned in the exhibition. I thought I would have to read all of these stories meticulously and do close-readings of passages to understand Rego’s paintings fully. However, as I started to delve into the stories, I realised I was wrong. Paula Rego makes these stories all her own. It doesn’t matter what story she bases her work on, because, inevitably, she will appropriate and interpret them creating original and unexpected compositions. Traditional stories are constantly being altered as they pass down through generations. Perhaps, Rego’s changes to them will impact the way we collectively tell these tales. I know that after seeing Rego’s “illustrations” I will.

Paula Rego, Folktales and Fairy Tales, was at Casa das Histórias, Cascais, Portugal. Paula Rego. The Cruel Stories of Paula Rego runs until 14 January 2019 at Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris