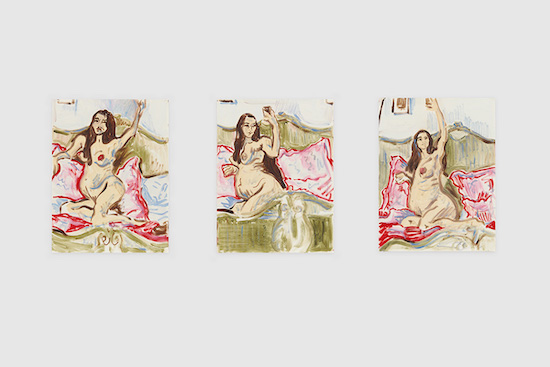

Rafaela De Ascanio (2019) 26 Weeks, I, II, III

Despite the slow thaw of lockdown measures in the UK, the online viewing room continues to act as the primary means of exhibition for galleries, necessitating a reconceptualisation on behalf of the viewer of what it means to “experience” art. Making use of this already destabilized ground, the London-based Cob Gallery’s new online group show, titled Paintings On, And, With Paper, asks the viewer to reconsider paper as an artistic material, examining it not as a primarily disposable art supply, but instead as a formidable site for permanent work. However, while this alone could prove a sufficient crux for the exhibition – after all, the current moment has forced us to think about notions of disposability, NEcessity, and making do – this lens provides a mere entrypoint. There is much more than simply medium that binds the work of the sixteen UK-based artists on display, who include Florence Hutchings, Lucia Ferrari, Christabel Macgreevy, and Aly Helyer amongst their ranks.

Immediately noticeable are the themes of domesticity and corporeality that feature heavily throughout, no doubt a product of our collective enforced isolation. Still, despite these palpable undertones, COVID remains no more than an oblique reference. Instead, significant prominence is given to explorations of the home’s otherwise ignored banalities, and by extension, the relation of the human body to those spaces where these banalities take on meaning.

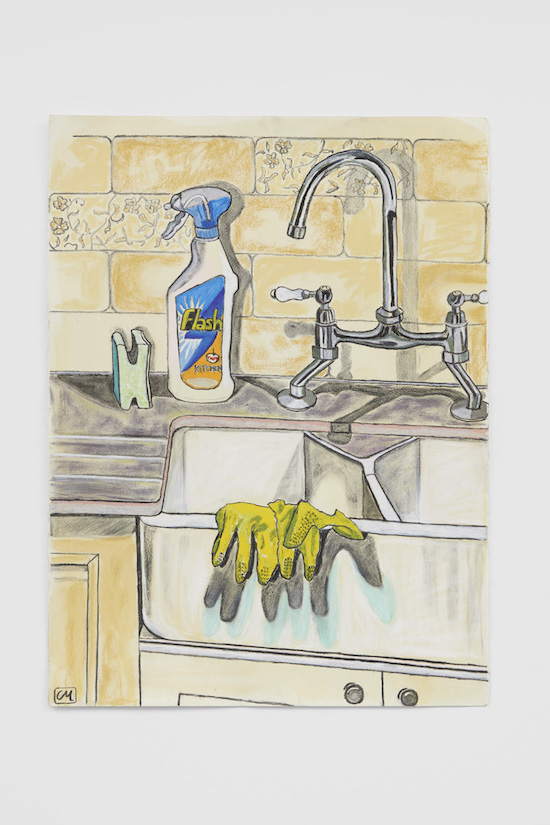

This can perhaps be understood most clearly in Christabel Macgreevy’s Sign Of The Times (2020), which draws into focus the forms of the kitchen sink and various cleaning products. As out-of-frame light sources illuminate the scene both frontally and from the top-right corner, we see the pronounced contrast of light and dark as it plays out on the metallic tap, its imposing height given credence by the strong shadow that lies below. Similarly, each sagging finger of the yellow rubber gloves that lie on the sink’s edge is given visual weight by the long shadows that extend beyond each tip. One could be forgiven for having (quite literally) never looked at their kitchen in such a light. Macgreevy’s composition, reminiscent of classical still lifes, invites the viewer to understand these objects’s formal qualities alongside their everyday utility.

In turn, Florence Hutchings’s The View From The Living Room Table, both I and II (2020), insert human perception into spaces often inhabited but rarely seen. In I, her rough style, while not reflective of spatial reality, depicts the scene as it is perhaps felt: personal space, with its titular table extending away from the viewer, is minimized in favour of the Georgian arched window and shutters that take up the top half of the image. As such, the self is made disproportionately small – and the world painfully large – in a kind of vertiginous reckoning with one’s own singularity amidst London’s bustling cosmopolis, the city where Hutchings lives and works.

With this kind of vertigo in mind, it becomes clear that anxiety does not lie far below the surface, most acutely perceptible when the domestic and bodily collide directly. In Aly Helyer’s Untitled (2019), a gloved hand runs across a child’s disfigured face, prompting consideration of the semantic parallels between that which is ‘beautiful’ and that which is ‘clean’, alongside notions of the body’s inherent ‘dirtiness‘. The figure’s left eye, drooping and unfocused, poignantly counterbalances his right, which signals fear, if not resignation. Perhaps this expression is born out of the recognition that the hand which ‘cleans’ does not discriminate in its determination of that which is ‘dirty’; the singular fault of the drooping eye is forced to act as metonym for an entire body that is deemed to have failed.

Christabel Macgreevy’s (2020) Sign Of The Times

Similarly difficult, Rafaela De Ascanio’s triptych 26 Weeks, I, II, III (2019) depicts a nude pregnant woman taking selfies three times over. Her body appears strained by the load it bears, and amongst the unstable outlines of pillows and blankets, its linear boundaries seem to grow ever-more diffuse. Yet, as the woman feigns obliviousness for her camera, the act of taking a selfie defies this lineal confusion: her body and its vicissitudes are flattened and reduced, simplified and packaged for others’ consumption. The deeply human reality of the belaboured body, and the tense domesticity bodily limitation can create, is rejected in favour of the glib veneer of presentability.

Indeed, it may be De Ascanio’s painting that best represents the show as a whole: despite (or perhaps because of) the palpable distress on display, the show is resolutely human. As each work either explicitly or contextually grapples with the exigencies of the contemporary moment, the viewer is given licence to experience all of the conflicting feelings surrounding isolation at once: comfort, fear, serenity, frustration. Despite the wide range of styles and subjects on display, the exhibit is made coherent by curator Cassie Beadle’s deft creation of an emotional continuum; each image, inflected by the tone and feeling of those around it, has something to offer the viewer. But, perhaps most impressively, Beadle refrains from being prescriptive. Offering no way forward in her curation, she simply creates space for us all to inhabit the moment, a phenomenon all-too-rare amidst the chaos of our times.

Paintings On, And, With Paper is online at Cob Gallery until 11 July