OOTB cover: ‘Chick’ by Nancy Fouts. Design by Stuart Tolley @ Transmission,photograph of book by Reiss M.

From my earliest memories I have always been fascinated by cabinets of curiosity and peephole dioramas, penny arcade automata on the pier to dusty old vitrines in long lost museums. These places still captivate me now, just like my recent discovery of The Shell Museum in Glandford, the oldest purpose-built museum in Norfolk. Amongst the fossil themed exotica are things as eclectic as a walking stick made from a shark’s backbone, a Nigerian ceremonial necklace, a Cromwellian cannonball, Chinese gambling discs, Fijian throwing stick, decorated turtle carapaces to Bellarmine stoneware jugs with bearded faces. It wasn’t just the sheer strangeness of this assorted collection, but the extraordinary story each item might be able to tell. As well as being inspired by the tactile artistry and possibility of the objects themselves, I found the ‘box’ or containment of these things equally fascinating, the staged significance in presentation. This interest also relates to my own practice as an artist, my attraction to the process of cause and effect, the union and collision between unlikely objects.

Out of The Box is a ten year labour of love, researching, curating and documenting exhibitions and events that focus on box art, a term I loosely defined as “artworks that have evolved, been created within, or have even escaped from a box”. This was how I worded my initial call out or invitation which seemed to engage with practitioners from every walk of life, whether professionals or those working outside the mainstream. However diverse their practice, all the artists share a penchant for collecting and using images, objects and materials, playing with conventions of perspective, subverting viewers’ perceptions through visual illusion. As a rule, creatives tend to be voracious collectors. Seeking, locating, acquiring, classifying, cataloguing, storing, and displaying are all vital practices to aid the artistic soul. However demented these activities might appear to others, they provide some kind of ordered path through the everyday. Like a souvenir, it is instinctive to preserve and protect the contents of such collections, whatever they might be – an act of remembrance that can determine how we inhabit the present. These micro worlds allow us to play curator and the display of the most humble object could be singularly transformed into something hallowed and holy. A perfect present-day testament to this process relates to musician Warren Ellis’s essential memoir Nina Simone’s Gum. The chewed gum itself is now housed in a glass case, on show at the Royal Danish Library for all to see.

I don’t think box art is necessarily a genre or a medium, so in attempting to bring some order to the wild spirit of this collective I have presented the study through four evolving chapters based upon the elements; decorative and serious, artefact and artifice all captured in miniature. Beyond the influential worlds of Joseph Cornell’s shadow boxes, I’ve also included photographic stories which make a veritable case for the function or necessity of a box. These photographers are also collectors sharing typologies of fading art forms, questioning who we are, inviting us to places we might never see, such as the storage archives of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Engaging with visitors from the earliest exhibitions I could witness an innate accessibility, touching all aspects of our lives, our daily rituals of rationalizing and organizing. We live, arrange, watch, and rest in death in boxes and this compendium is testament to the absurdity and wonder that is life.

Richard Johnson

Ice Huts by Richard Johnson

The late Richard Johnson used large-format digital photography to document the structures that shape our cultures and communities, preserving such places in a rapidly shifting world. Inspired by the work of mid-twentieth-century German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher, Richard’s Ice Huts series records the temporary ice-fishing huts and villages that populate many Canadian waterways during the winter. In tightly cropped compositions, Richard fixes his lens on the formal and material qualities of the architecture and examines its relationship to site, revealing the creativity, character, and humour of these hideaways.

Each of the structures in the series glows with an aura of wonder and rustic significance. Born of a need for sustenance, ice fishing was handed down from such indigenous peoples as the Inuit, whose lives depended on the scant resources offered by an apparently inhospitable landscape. But even for Richard’s modern-day hinterland voyagers, the basics remain the same: the huts have openings in the floor, and the fishermen must cut holes in the ice, the size varying depending on whether they are using a line or a spear.

With a background in commercial interior design, Richard was attracted to architectural photography by the simplicity of these renegade, folk-art constructions. “It is architecture at its most

primitive level,” he says. “It’s shelter. It’s portable. It’s made by the owners of the hut. It’s not pretentious. It is a solution. Every single person needs heat.” Of his photographs of the huts, he says: “For me, these are really portraits of the individual. But the individual is not present.”

Each year, entire ice-fishing villages are abandoned as the ice melts, only to be reconstituted the following year. Unseasonally high temperatures can sometimes drive the same villages onto a farmer’s field or open ground – groups of huts with cows and rabbits instead of fish and ice. Richard described these gatherings as “ice villages on holiday.”

Nancy Fouts

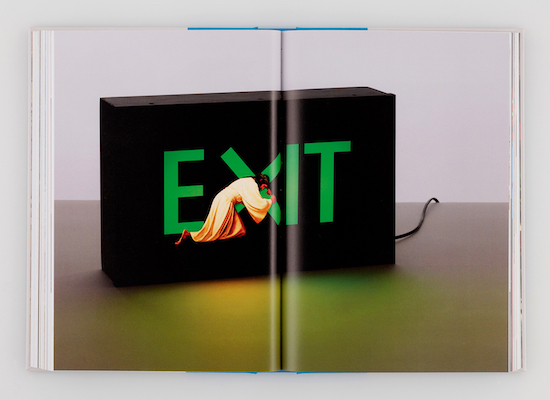

Exit Jesus by Nancy Fouts. Book photography by Peter Mallet

The late Nancy Fouts was a modern-day surrealist. Her provocative sculptures made of reconfigured objects and ephemera revelled in the inherent strangeness of the familiar. Her wild imagination was fuelled by an endless love of collecting, which she described as “beachcombing,” creating a visual poetry out of unlikely combinations, mischievous modifications, and subversive wordplay.

Born in Seattle, Nancy was sent to London at the age of sixteen to attend a finishing school in Pont Street, Chelsea, called the Three Wise Monkeys (also known as the Monkey Club because the girls were taught to “hear no evil, see no evil, and speak no evil”). Fouts first rose to attention in the Swinging Sixties, painting shopfronts in Carnaby Street before co-founding the illustration agency Shirt Sleeve Studio with her then husband, designer Malcom Fowler. Their workshop produced many designs for record sleeves, including some for Manfred Mann and the award-winning design for Steeleye Span’s Commoners Crown.

For many years she worked as a model-maker in the advertising industry, creating seminal campaigns for Silk Cut, British Airways, Benson & Hedges, and Virgin. Working in the commercial field gave Nancy an acute sense of observation, while also allowing her to develop her own working methods. Self-sufficient and ingenious in finding solutions to technical problems, she rarely used assistants – unlike many contemporary artists, who use technicians to fabricate their works.

Guy Tarrant

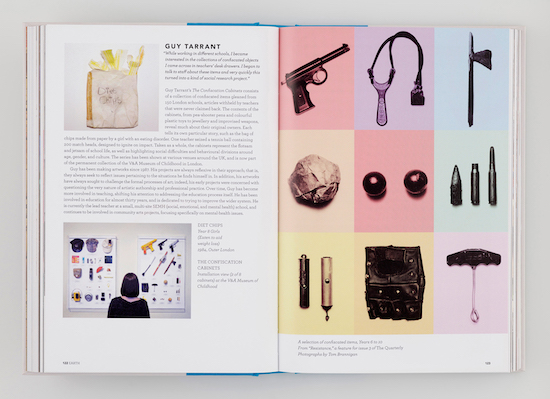

The Confiscation Cabinets by Guy Tarrant. Photography by Tom Brannigan & Peter Mallet

“While working in different schools, I became interested in the collections of confiscated objects I came across in teachers’ desk drawers. I began to talk to staff about these items and very quickly this turned into a kind of social research project.”

Guy Tarrant’s The Confiscation Cabinets consists of a collection of confiscated items gleaned from 150 London schools, articles withheld by teachers that were never claimed back. The contents of the cabinets, from pea-shooter pens and colourful plastic toys to jewellery and improvised weapons, reveal much about their original owners. Each tells its own particular story, such as the bag of chips made from paper by a girl with an eating disorder. One teacher seized a tennis ball containing 200 match heads, designed to ignite on impact.

Taken as a whole, the cabinets represent the flotsam and jetsam of school life, as well as highlighting social difficulties and behavioural divisions around age, gender, and culture. The series has been shown at various venues around the UK, and is now part of the permanent collection of the V&A Museum of Childhood in London. Guy has been making artworks since 1987. His projects are always reflexive in their approach; that is, they always seek to reflect issues pertaining to the situations he finds himself in.

Mohamed Hafez

Desperate Cargo by Mohamed Hafez

hiraeth (n.), a homesickness for a home to which you cannot return, a home that maybe never was; the nostalgia, the yearning, the grief for the lost places of your past.

Mohamed Hafez is a Syrian American artist and architect. Born in Damascus, he was raised in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and educated in the Midwestern United States. When he first moved to America from Syria, not long after the events of 9/11, a fear of Islam and Muslims was at its peak. President George W. Bush’s travel regulations were targeting Muslim-majority countries, while Syrians were being lumped in with other Muslims, indistinguishable in the American mind. In recent years, Syria has been rocked by a bloody civil war.

The atrocities of the conflict are reflected in Mohamed’s art through his use of found objects, such as paint and scrap metal. Making the most of his architectural skills, he creates surrealistic Middle Eastern streetscapes depicting cities besieged by war, capturing the magnitude of the devastation and highlighting the fragility of human life. In deliberate contrast to the violence of war, however, his art takes hope from the richness of thousands of years of history as well as verses from the Qur’an. Existing at the core of Mohamed’s work, the verses offer the prospect of a bright future compared to the stark reality of destruction.

Marcius Galan

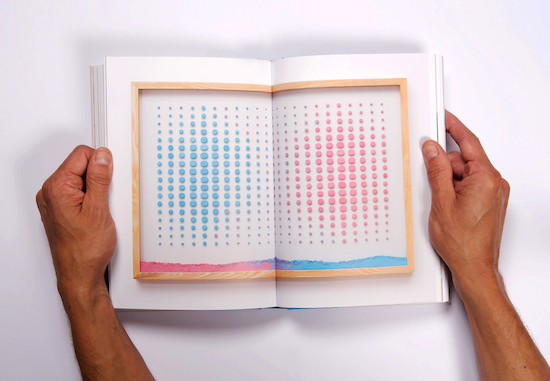

Erased Composition by Marcius Galan. Photography by Marcelo Arruda & Reiss M.

The work of the São Paulo-based artist Marcius Galan encompasses sculpture, objects, drawing, and other media, all characterised by a very precise approach to art-making and a particular interest in geometry. In many of his pieces, Marcius carefully reconstructs objects that have been subjected to suppressions or additions, redefining certain aspects of their functionality and form. By intentionally undermining their use-value, Marcius addresses the relationship of these objects with social structures, bureaucratic processes, and economic systems.

Marcius’s eraser drawings are formed by the obsessive action of repeated drawing and rubbing-out. The frustrated attempts to build these primary forms tell the story of a drawing that is not actually there. He began these works by framing all the residue generated by the erasers he had used for successive drawings over a four-year period. Later, he became more interested in the material itself– in its original form – rather than its remnants. This led to more formal experiments with erasers, in which new or half-used erasers, together with graphite sticks, are arranged in boxes to form immaculate geometric compositions.

In relation to the initial drawings, Marcius describes a dematerialization of the drawing process, reduced to the materiality of the tools themselves. Interestingly, Marcius is an artist for whom emptiness holds such a fascination. The works effectively extend the notion of the artist as creator of ideas, in the manner of Marcel Duchamp’s iconic readymades or Robert Rauschenberg investigating whether an artwork can be produced entirely through erasure.

Docubyte

Telefunken RA770 by Docubyte

James Ball, aka Docubyte, is a photographer, retoucher, and art director. His mantra is technology is beautiful. “I’m a huge fan of analogue, vintage things,” says James. “Dials, switches, and knobs have such a timeless, retro appeal and a kind of innocent charm in the current world of slick, tech gadgetry that I wanted to address this photographically. I began thinking about building a kind of vintage machine myself, but in researching the kind of things I was into, I realized that so many machines existed that looked like what I had in my mind. I didn’t need to build anything myself: the analogue machines of my fantasies actually existed in real life.”

It was James’s interest in documentary photography and his work as a retoucher in the advertising industry that led to “Docubyte” – a coming-together of his passion for historic machines and skill in digital beautification. The series Guide to Computing celebrates the world of computers between 1945 and 1990, documenting their evolution.

After establishing where he could find a particular machine, James would then arrange a photo shoot. His biggest challenge, given the various locations in which he had to work, was in making the computers look as though they had all been photographed in the same place. Shooting some of them behind glass, such as Alan Turing’s Automatic Computing Engine (ACE), proved an additional challenge, but fortunately many of these issues could be resolved in Photoshop. A number of the computers predate modern colour photography; James’s visual love letter to the technology of yore thus allows us to see them in an entirely new light.

Jay Ross

Empty Signs by Jay Ross

Jay Ross’s Empty Signs is an anthropological collection of photographs of blank, broken, and otherwise empty American signs. The process of documenting the signs began in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 2012 and continues to this day, capturing signage in Louisville, Kentucky; Michigan; San Antonio, Texas; and predominantly Columbus, Ohio, where Jay currently resides.

The project asks as many questions as it answers, if not more. Are the signs a romantic road map of the American dream, or are they rusted symbols of a “boom and bust” economy? Either way, there is an innate beauty to these vacant vessels, one that could tell many stories. Among other things, they bring to mind Julien Temple’s Requiem for Detroit? (2010), in which he describes the near-deserted metropolis of the film’s title as fast becoming the first “post-American city.”

Ross’s empty signs are universal remnants of a rich past of promise and production. Perhaps they represent voids to be filled with hope, an exhilarating opportunity to start over, pioneer’s map to a post- industrial future that might await us all.

Michael Johansson

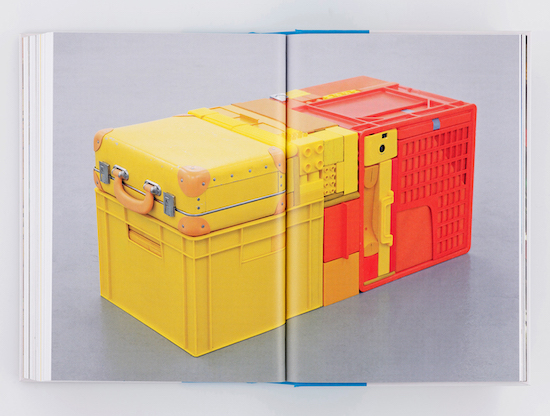

Tube by Michael Johansson. Photograph of book by Peter Mallet

“I am intrigued by irregularities in daily life. Not those that appear when something extraordinary occurs, but those that are created by an exaggerated form of regularity. Colours or patterns from two separate objects or environments concur, like when two people pass each other dressed in the exact same outfit. Or when you are switching channels on your TV and realise that the same actor is playing two different roles on two different channels at the same time.”

Swedish artist Michael Johansson re-contextualizes the readymade, freeing mundane objects from their function to produce geometric sculptures and perfectly constructed installations. His real-life Tetris pieces are recognizable yet unique, archaeologies of everyday life compressed into harmonious rectangles or cubes. His sculptures could perhaps be seen as contemporary still lifes, yet they are abstract in the way in which disparate parts have been puzzled together according to shape and colour.

Objects can often be read like words, making sentences. With his distinctive way of handling objects, presenting them en masse, Michael tells a story while building a sculptural design. His use of a consistently monochrome colour scheme bestows his works with form and visual calm, reflecting his obsession with finding doubles of seemingly lone and often useless things. These works comment on our relationship with objects and are proof positive of the possibility of thinking inside and outside the box at the same time.

Out of The Box’ – A celebration of contemporary box art – is published by Eight Books