Urth by Ben Rivers

It’s easy to get bored of Utopia. It seems every week another flashy digital render of some imaginary sci-fi city is presented as our collective future and rescue from the Anthropocene. Whether it’s a 170km line through the Saudi desert, floating villas in a Maldives lagoon, or an urban plan shaped into a giant B for Bitcoin in the shadow of an El Salvador volcano, such glorious projections of a human future just seem unreal compared to the existential challenges we seem to be coming up against. When looking at such contrived utopias, I can’t help but wonder perhaps we shouldn’t put our collective salvation in the hands of messiah-like starchitects, multi-billionaires, and Bitcoin tech bros.

It’s a kind of messier, less immaculately planned urban future under consideration here at Our Silver City: 2094. Set up as if we are looking backwards at imagined periods of Nottingham seventy-three years from now, like the Great Flood and Freeze of 2071 and a migration from the city to the forests in the following years. The gallery acts as a kind of archive presented by imagined future-historians, documenting how people recorded, fought, or reimagined society. This all makes it sound like it could come across as dark and heavy – perhaps the last thing we need mid-pandemic – but instead the four rooms focus on abstracted objects, films, and artworks which speak to collaborative restoration, mutual care, ecological awareness, and craft approaches to rebuilding.

This co-operative, collaborative approach is hardwired into the making of the exhibition as well as within the exhibited works. There was no single curator. Instead, a non-hierarchical model in which three lead artists and writer Liz Jensen riffed off a narrative idea from instigator Prem Krishnamurthy. At a time when the Turner Prize concentrates on collectives, it’s a novel approach to exhibition-making, and perhaps offers a route towards new ways of presenting culture.

Each of the four rooms has a different conceptual underpinning, and a starkly differing aesthetic. Upon entering the first gallery, dedicated to “time of change”, a tapestry weaved from emergency blankets by Eline McGeorge hangs above Sandra Mujinga’s Octo Clutch / Temporary Home sculpture of a smashed Perspex screen seemingly fallen from a great height, crushing some unimaginable creature – a coupling immediately setting a tone of cataclysm and repair. The same room has its share of optimism, too. In Asad Raza’s film Ge we observe a recording of him teaching his daughter how to make a living soil medium for new growth using food waste and sand interspersed with footage of the Dorset coast landscape (a place that has served as both inspiration and home to James Lovelock). One Hour Sun Drawing by Roger Ackling speaks to time and energy by scarring geometric forms directly onto the page by channelling the sun’s force, while Nicola L’s Ciel bodysuit hangs limp from the wall, as if waiting for a medical expert to enter it from the other side and examine Covid-weary visitors.

Our Silver City, 2094. Installation shot at Nottingham Contemporary, 2021. Photo Stuart Whipps

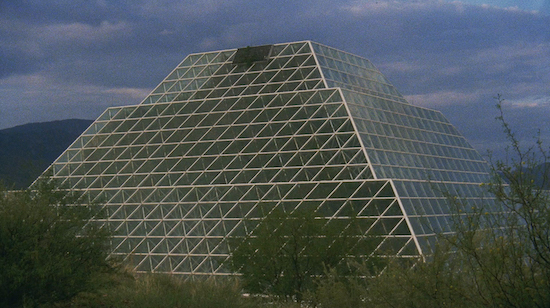

The second and third galleries, led by artists Céline Condorelli and Grace Ndiritu respectively, have individual structural and sculptural aesthetics. Condorelli has built a framework of hanging prints. A vegetable-dyed cotton curtain hangs to divide the space and give shelter to Urth, a Ben Rivers film imagining the last woman on Earth and her final notes on human relationship with the natural world. It’s a room designed with a very singular aesthetic by Condorelli, but one which starkly changes when entering Ndiritu’s adjoining room with its huge temple-like timber structure by the artist, from which unexpected and playful objects are displayed.

A totem tower of synthetic hair by Vivian Lynn stands as if from some twenty-first century folk culture we have yet to create. An owlish stoneware jar with a furry tail seems to be awaiting offerings and a vitrine of mementos and Angus McBean photographs of the pre-WW2 Kibbo Kift youth movement speaks to future creative communities we may need to (re-)invent to face the upcoming struggles. In what is the strongest of the four rooms, an eclectic hang including Anni Albers screenprints, retro-modernist tapestries by Armando D. Cosmos, and assorted historic ceramics from the city’s museum collection come together to create a timelessness hovering between the previous and next centuries, perhaps inviting future-history rhymes, learning from the better parts of our last century.

Our Silver City, 2094. Installation shot at Nottingham Contemporary, 2021. Photo Stuart Whipps

The final gallery, led by Femke Herregraven, is altogether more stripped back. A white daylight-filled room in which a series of sculptures wrought from metal, driftwood, and parachute cord stand like improvised scientific apparatus. A spatial sound composition by BJ Nilsen darts around, with sporadic children’s voices interrupting, reciting idioms of weather prediction in response to real-time data collected from the gallery’s roof – “When black snails on the road we see, then tomorrow rain there will be … When the moon is high, expect cold weather.” Drawn onto the walls of the room are symbols of a new meteorological notation system, suggesting we will need to re-discover relationships to the natural environment neglected through the industrial years.

Without a curatorial text and precious little wall information to bring forth a lead story of each item across the four rooms, it is left to the individual visitor to draw connections between – and ideas from – the heady mix of pieces. Jensen’s novella offers a narrative thread from which all the artists’ ideas spill, but for any reader that doesn’t have the time or awareness to dive into the text (fascinating and well-crafted though it is) the collaborative, exploratory nature of the exhibition does perhaps mean the focus can get diffused or confused, especially with such sharp shifts in mood and aesthetic between each room. There’s a sense of four distinct exhibitions rather than a durational journey.

Perhaps, though, this slight looseness or lack of clarity is also critical. With a singular curator at the helm there may have been tighter structure and narrative, alongside blurbs to encourage the visitor to expected conclusions. But the nature of collaboration and collectivism can lead to gaps, soft-edges, and a less authoritative scripture. Perhaps the futures we need to carve are less systemically top-down and more exploratory, more plural.

Our Silver City, 2094 is on at Nottingham Contemporary until 18 April 2022