“If you take the history of twentieth century painting, once you get to Pollock and abstract expressionism, it’s all about the wall and the surface and things being flat and opaque. Whereas if you put the twentieth century to one side, the window is a much more relevant subject position, and it’s also an extremely popular motif from the renaissance to the nineteenth century and further back. But in the twentieth century it fell completely out of favour. It became quite kitsch.”

The work of Oliver Osborne has always supported an expanded view of the history of painting. His new show at Vilma Gold Gallery in London contains several windows, and many other frames enclosed within the picture frames on the wall. In some respects, then, this is a show of paintings about paintings, and about the frames (both physical and referential) we put them in.

But it is also a very intimate and quite personal show. A show about change and constancy. Perhaps most importantly, it is a show about Europe. About European painting, yes. But also about Europe itself. The idea of Europe. The European dream. And a cat called Schengen.

Schengen is the name of a small village in Luxembourg with a population of 4,223. In the far south-eastern tip of the country, it borders both Germany and France – which made the morning commute to work quite frustrating for the town’s Luxembourgian residents when, every morning, they set off to work in Saarbrücken or Metz, through customs officials and passport checks. So it made sense that the agreement to make an irrelevance of those borders between Luxembourg, Germany, and France (and Belgium, and the Netherlands, and later Spain, Portugal, Denmark, Sweden, Liechtenstein, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Austria, and the Czech Republic) would be signed there in 1985.

For those, like me, who believe that national borders are one of our greatest barriers to progress, the Schengen Area must seem like one of the most important political projects of the late twentieth century. But right now the project is under threat. Since the terror attacks in Paris last year, coupled with the ongoing so-called ‘migrant crisis’, national borders are once more being enforced within Europe. Once abandoned border posts and guard stations are manned once more. The dream is crumbling.

Oliver Osborne, Schengen, 2016, Silkscreen on linen, 215 x 164 cm. Image courtesy of Vilma Gold, London

I’m thinking about all this as I stand in the middle of the Vilma Gold gallery and look at a 215cm x 164 centimetre work called Schengen. It’s a silkscreen on linen of a cat with its back arched, poised above a horizontal line, a divide in the material within the frame: a kind of internal border of the image. I’m thinking about about borders and I’m wondering: why does the cat look so scared?

“I can kind of imagine a Brussels bureaucrat with a cat called Schengen,” Osborne tells me. We’re talking via Skype to his studio in Berlin, two days after I visited the show at Vilma Gold. “But also cats don’t respect borders,” he says. “That’s part of their thing.”

Osborne, who describes himself as “a very passionate European,” has lived in Berlin for several years now. “My interest and understanding of painting and of art,” he says, “has largely come from living in Europe and visiting museums in Europe.” A new book about his work, from Mousse Publishing, featuring essays by Terry R. Myers and Nicholas Hatfull, is entitled European Painting. The title, he tells me, “sounded amusingly old school. Like it’s some sort of an anthology of European painting.” But a certain Europeanness pervades the images in the book – and in the present show at Vilma Gold too.

Installation shots, Oliver Osborne, False Friends Falsche Freunde, 2016, Vilma Gold, London. Image courtesy of Vilma Gold, London

The exhibition is called False Friends. Many of the images it appropriates are taken from language textbooks. “It’s a kind of analogy,” Osborne says, between the decoding of an artwork and the translating of a foreign language, “there’s no state of total comprehension.” Other images come from cookery books. These cartoons are lifted from a context in which their meaning is very clear and direct – to educate or instruct in presumably as unambiguous a fashion as possible – and then screen-printed or embroidered onto a large white canvas (a “forensically clean” canvas, as Osborne puts it) where their meaning or intent suddenly becomes much more ambiguous. In Fish (2016) we find a simple line drawing of a dead fish clasped by thumb and finger. Evidently once part of a diagram detailing how to fillet a fish, now its arrows point to nowhere.

“I often take things that are completely un-mysterious,” Osborne explains, “as deliberate and practical a demonstration as how to fillet a fish. By stripping it and reducing it, it becomes actually a completely unpointed and enigmatic image. It is a fish,” he says, “but it’s not – it becomes a question.”

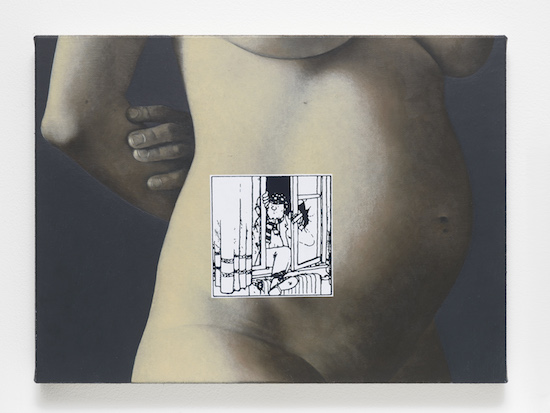

Interspersed and sometimes interpenetrated with these comic images, there are rich, carefully worked oil paintings, beautifully executed, of a rubber plant and a pregnant woman. It is part of the magic of Osborne’s work that the combination never seems jarring. A screen-printed line drawing and a far more labour-intensive painting sit side by side without quite being juxtaposed. “It’s not just that I appropriate images,” Osborne explains, “it’s that I appropriate painting as an image. It’s appropriating a certain kind of painting which can then become its own kind of abstraction. In this show, everything is kind of a picture.”

False Friends Falsche Freunde by Oliver Osborne is at Vilma Gold until 18 June