Phil Collins,dünya dinlemiyor, 2005.© the artist.Part funded by the 9th International Istanbul Biennial. Courtesy Shady Lane Productions, Berlin and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

Perhaps this is not the best time to title an art show after a line in one of Morrissey’s songs. Stephen Patrick Morrissey’s rank has mutated alarmingly over the years. Initially received with rapture by the indie masses, desperate to be reprieved from the then all-pervasive kitsch of New Romantic pop, he soon became something of an eccentric national treasure. An Edith Sitwell for an anaemic youth marinated in self-pity. And then the Smiths split up and a steady drip feed of verbal silliness over the years has led now to the desertion of long-standing champions. His currently divisive status in the UK seems split between those who regard him as a near unspeakable pariah and a diminishing band that still think him a champion of a strained form of Englishness.

The song line chosen for the title of this show in Eastbourne is taken from one that is far from his best. Shoplifters of the World Unite sounds to these tired ears like U2’s Bullet the Blue Sky – a shot at pompous stadium R ‘n’ R. One suspects from his recent communications that Morrissey has become more at one with the cantankerous state of the nation. He’s a shopkeeper at heart demanding that whatever we once took we now hand it back, hand it over. Hand it over to Ronnie Pickering with a quiff.

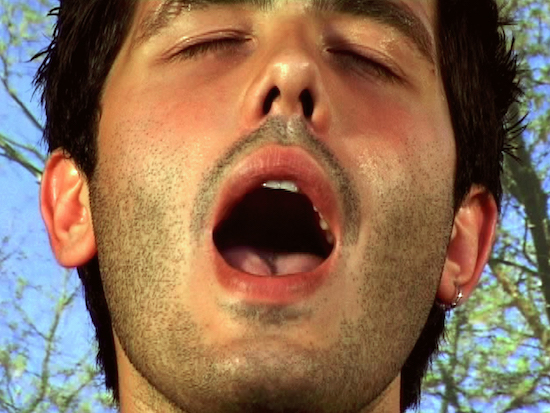

Taking a cue from the (deserved) success of early Smiths recordings, this is purportedly a show about art inspired by popular culture. The fit of the works feels a tad forced, like a groovy geriatric trying to squeeze into a new pair of trendy trainers. The concept is not new. Artists have been taking the poptastic world of mass entertainment seriously since, oh, Stuart Davis at least in the 1920’s, if not earlier. Phil Collins dünya dinlemiyor (2005) is an enjoyably excruciating video of Istanbulli youth impersonating our Morrissey in a karaoke session. Every track from the compilation album The World Won’t Listen is covered.

The video, we learn, is the second part of a trilogy; the others were filmed in Colombia and Indonesia. We wince at many of the performances. Some are not bad, some awful, some touching. This is the art of embarrassment: a study of modern egocentricity. We see one overly earnest fan with flowers in a back pocket mimicking Morrissey’s mannerisms. But it is the gap that interests Collins – the chasm that divides the wish fulfilment fantasies of crazed idolaters and the mundane reality of their daily grind. Mind you most of them seem to be having a whale of a time…

Mark Leckey,Parade, 2003. Courtesy the Artist and Cabinet, London.©the artist. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London. Part funded by the Film and Video Umbrella

The hits just keep on coming. Jim Lambie’s Sid Vicious (2001) is not his best work perhaps, but this reflects my strong antipathy to the man who usurped Glen Matlock. A paper, board, and glitter construction features an image of said dead Sex Pistol puffing on a spliff. If one has to have a Ritchie, give me Lionel over John Simon any day. Another Lambie sculpture, Frankie Teardrop (2001) – a line of coloured beads suspended from a ceiling by a nylon thread – might have been a more prescient punk-related work given Alan Vega’s higher claim to persistent relevance and power, but sadly it isn’t here. Ross Sinclair’s T-Shirt Painting (no.1-80) (1993–1998) is great – a collection of multicoloured garments hanging together as if on some gigantic washing line. We face a grid with a visual zap worthy of Ellsworth Kelly. Each bears a slogan that references variously, musicians as heroes (Teenage Fanclub and Rod Stewart), Scottish history such as ‘Culloden is Lost 1746’ and ‘Bannockburn is won 1314’, and Clash song titles like ‘White Riot’ and ‘1977’.

Jeremy Deller’s The Uses of Literacy (1997) features collected detritus belonging to fans of the Manic Street Preachers. And so we get adolescent drawings of doomed Richey, some fanzines, and a small library of sixth form classics – a line of tattered paperbacks by Orwell, Larkin, Salinger, Plath, and Primo Levi. The work looks curious now, in the light of the Manics increasing drift into peripherality. In fifty years time the installation might be meaningless without an extensive corpus of notes maybe entitled The Kids Used to Love these Guys. Art about obsessions, fandom and taste – for now the work remains an insight into the persistent mystique of the cultish.

Deller’s The History of the World (1998) is a well-worn screenprint diagram that tries to link acid house with brass bands. Funny at the time, but – ouch – that joke isn’t funny anymore. The link between the two genres is humorously tenuous to say the least. On the plus side he does namecheck 808 State and A Guy Called Gerald. But that’s enough of my obsessions, fandom and taste…

Matt Stokes is also interested in subcultures and the idea of evolving musical styles that stimulate the development of a new collective. Jubilee Dancer (2011) is grainy footage of an unofficial rave in Cumbria taken with a night camera. We see a pair of baggy pant-wearing legs jigging lazily. These belong to a Bez lookalike who drags on a fag whilst doing that pithed frog dance beloved of the Happy Monday’s dancer/prancer. All this is accompanied by a rather irritating loop of a folk reel. Annoying, because this bleeds incessantly into the gallery space and so compromises the intelligibility of the other works.

Jeremy Deller,The History of the World,1998. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London © the artist

Mark Leckey’s video Parade (2003) is an enthralling autobiographical tease, a personal memory trawl. We see a sequence of images (often shot on the street at night) that allude to the artist’s youth and the cultural influences that formed him, consciously or – more interestingly – subconsciously: shopfronts, pictures of models, the young Adam Faith posing, and all of this soundtracked by short loops of ghostly tunes, heels clicking on pavements, snippets of conversation. The title of the work seems to relate to the adult magazine sold in British shops when Leckey was growing up.

Contemporary cinema is the other zone of popular culture addressed at the Towner but it gets the rough end of the deal. The works positioned here suffer in comparison to those referencing pop music. This is partly due to their silence. They are not supposed to be accompanied by the sound of penny whistles or someone yelling Hang the DJ. And the movie-related works are more modest in presentation and impact. John Stezaker’s Psycho Montage III (The Mirror) (1978) captures a Hitchcockian encounter with a reflected doppelgänger. Mario Rossi’s The End/Untitled, series (1996–2000) are acrylics on canvas that feature the final shots of the over-referenced Psycho (1960) again as well as those from some lesser pictures such as True Grit (1969).

Maybe the problem with this show is the central concept. Arguably pop just isn’t that popular anymore. There’s an air of Smashy and Nicey about it all – a B.T.O. you ain’t seen nothing yet hankering for an imagined time of pop glory… the Manics? Not ‘alf mate. You can almost hear a resurrected Alan ‘Fluff’ Freeman saying – ‘and incidentally music lovers how’s about some Throbbing Gristle?’ The Towner show majors on the pop pickers of the recent past and as such is profoundly nostalgic. You leave asking, is it possible that the world once invested so much in the Manics? Art about pop; the sound of one Linn drum clapping.

Having said all the above this is an ambitious show at the Towner. Being reacquainted with these works curated in a variant of the shuffle format means inevitably that some jar whilst others, gulp, shine a light that never goes out.

Now, Today, Tomorrow, And Always, is at the Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, until 8 October 2017