Imagine an estate agent’s spliced with a derelict house and you’ve got the feel of Nick Barrett’s new exhibition. Ruinous real estate chic. For London Stock, Barrett’s first solo show, a crumbling Victorian house in Peckham has been transformed into an immersive installation, blending the glossy sheen of a show-home with a Dereliiiiiicte glamour.

If you’ve seen the comedy blockbuster Zoolander, you’ll remember Derelicte as the fashion line designed by Mugatu (Will Ferrell) and worn by male model Derek Zoolander (Ben Stiller) of Blue Steel fame. Inspired by a controversial, real-life fashion show in 2000, designed by John Galliano for Dior, Derelicte showed catwalk models in rags and newspapers, accessorised with whiskey bottles and safety pins.

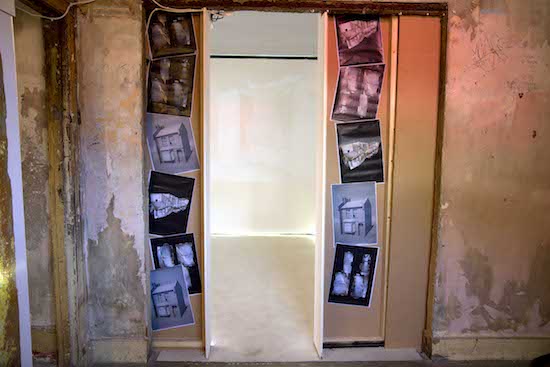

If Zoolander used film to satirise the New York fashion industry, London Stock uses art to parody the world of London housing development. Here, we see slick imagery of dilapidated brick walls, while a video gives us a virtual tour of the crumbling building we’re standing in. Watching this pseudo-promotional video, I thought of Francis Bacon paintings and Tomb Raider video games. Bleak, yellowing rooms rendered in CGI.

Most real estate imagery offers shiny, white-walled rooms upon which we can project our deepest domestic desires. In London Stock, Barrett flips this idea on its head, marketing a crumbling old house as a valuable asset. For the exhibition, the walls are adorned with Barrett’s beautiful, gold-leaf prints, while iconic London stock bricks are reimagined as gilded objects. Imagine what you could build here, the artist seems to be saying. This decrepit building is a gold mine – the perfect investment opportunity.

Throughout the exhibition, Barrett references the London stock bricks used during the house-building boom in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Created from brickearth and London clay, mixed with ash from the burning of the city’s rubbish, these bricks exist as an almost literal embodiment of London. Alongside historical references, London Stock alludes to a range of contemporary issues, most notably the commodification of housing and its status as an investment tool.

Barrett is interested in the different elements of urban change, in particular gentrification, the subtle, drawn-out process where working class areas are infiltrated by the middle- and upper-class. As the exhibition literature puts it, the exhibition explores “the conflicts buried within the mindset of the aspirational classes … a desire for stability and home ownership contrasting with a social conscience relating to gentrification and fears of social cleansing”.

Peckham is a fitting place to explore these kinds of issues, an area that’s become increasingly gentrified in recent years. Housed in a building next to Copeland Park – an abandoned warehouse turned creative hub – London Stock confronts the contentiousness of urban change, the external and internal conflicts.

Many Londoners feel conflicted about gentrification, understanding their complicity in a highly unequal process of social engineering. But does awareness stop people from buying property? Does a social conscience make people less susceptible to seduction-by-real-estate?

In the first room of London Stock, a window has been built into a wall, housing a collection of glass Coca Cola bottles. Anyone who has walked past a Foxton’s will get the nod to the street-facing fridges in luxury estate agents, displaying enticing soft drinks and alcohol for clients.

What’s clever about Barrett’s Coke bottles is the way he turns a consumer item into a kind of souvenir. Mimicking the aesthetic of those bottles of sand you find in gift shops on holiday, Barrett’s sculptures ripple with layers of different-coloured brick dust, reflecting how property is aestheticised, fetishised, in capitalist societies.

The use of net curtains in a second floor room is also a nice touch, adding an unheimlich chill to the show. In a room facing the street, a 3 x 2.17m cuboid of white net curtains surrounds a bare lightbulb. The space reflects the government-proposed minimum for a room within a new-build, 6.5 sq m (70 sq ft).

As the sun sets on the street outside, shards of light illuminate the curtains’ floral patterns, creating a beautiful shadow display. A baby’s cot flickering with pictures from a mobile. The ethereal beauty of this space contrasts starkly with its inhumane proportions, highlighting the sense of conflict that runs through the show.

There’s a hint of Rachel Whiteread in Barrett’s use of negative space. Looking at his empty bedroom, I thought of Whiteread’s casts of everyday objects, and her most famous work House, where she cast the interior of a Victorian terrace. But as I moved through London Stock, the artist I thought of most was Gordon Matta-Clark, his concept of ‘anarchitecture’ – a conflation of the words anarchy and architecture – and in particular his interest in the voids, gaps and left-over spaces in cities.

For Fake Estates (1978), Matta-Clark purchased fifteen unusably small slivers of land across New York, paying twenty-five to seventy-five dollars per plot. Documented through photographs, maps and deeds, these tiny bits of land revealed the absurdity of private property, using the bureaucracy of real estate to critique the system. London Stock blends some of the playful intelligence of Matta-Clark with the visual subtlety of a Whiteread sculpture. It’s clever stuff, appealing to both the intellect and the eye.

The final room of the exhibition, adjacent to the Whiteread-esque space, contains an array of tall sculptures, reaching towards the damp ceiling of the house. Toying with the aesthetic of real estate signage, they look like For Sale signs bent by the wind. Crooked objects topped with abstract paintings (rather than wording) in multi-coloured metallic tones.

There’s something trippy about these signs, a hallucinogenic quality that could perhaps signal the illusory nature of property, the absurdity of material desire… But they’re also just nice to look at, adding a painterly element to a high-concept exhibition.

Since the development of Canary Wharf in the 1980s and 90s, London has increasingly become a neoliberal utopia for the rich. Huge swathes of housing stock are owned by foreign investors, who buy-to-let or use properties as second homes. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of properties lie empty – especially in central London – amid a crisis in social housing and rising levels of homelessness.

At a time when the UK is experiencing a housing crisis, London Stock is a topical and provocative exhibition. Everyone has an opinion on housing, in London and across the UK, but what’s great about this show is that it raises questions without offering opinions. Rather than making fun of the housing market – as Zoolander does to the fashion world – London Stock asks us to consider urban development at a fundamental level. To question the foundations of the city around us.

London Stock was at Safehouse 2, Peckham, until 27 September. For more from Annin Arts check out their website