Photographs by Marion Bornaz, courtesy of Nuits Sonores

By the time I join her, Nan Goldin is already on stage, seated in a grey armchair, her auburn hair falling freely to her shoulders, corkscrew curls obscuring much of her forehead. She’s leaning forward, her hands clasped, their scarlet fingernails catching the light, with her gaze directed at the floor as though she’s thinking about where else she can go, and just how soon she can get there. I settle myself hurriedly onto a long sofa beside her in front of a packed audience that’s gathered in a conference hall so big it reminds me of the United Nations General Assembly.

Roused from her reveries, Goldin looks me up and down warily. A microphone sits next to a can of Red Bull on the table in front of her, while another mike lies next to me. Realising I have no time to lose, I pick it up and give my notes a final glance. After apologising for keeping her waiting – something that, considering recent events, seems mildly ironic – I dive in.

“Thank you very much for joining us,” I say, my voice audibly trembling, partially due to nerves, partially due to the exertions I’ve gone through getting here. “I wanted to ask a few questions, and see if people wanted to ask more afterwards.”

A mischievously impatient look on her face, Goldin shakes her head, staring at the floor once again. I hear a few titters from the audience. Her microphone remains on the table.

“They don’t?” I stutter. This idea’s not normally knocked back so fast. “OK. Then we’ll just lead with my questions…”

She leans back, legs crossed so they point away from me towards the audience. Spooked by her silence and body language, I rustle my notes again. I’m almost entirely unprepared for our encounter, and, with my heart thumping so loudly I’m sure the microphone can detect it, I decide simply to present the first question my eyes alight upon. It’s not the smartest decision I’ve ever made, and I recognise that even as my lips part.

“Sorry for starting with this, because I’m sure it’s not the easiest thing to begin with, but much – if not all – of your work, has been a response, I think, to the death of your friend Barbara.”

Goldin looks at me, her eyes a little glazed, before a fire ignites behind their irises. She blinks, as though trying to extinguish it, and looks at me in disbelief.

“My friend?” she whispers, a puzzled frown rippling her brow. “That was my sister.”

Few people beyond the front rows can hear what she’s said, but this does nothing to reduce the impact of her curt, straightforward statement. It doesn’t help, either, when she mutters her next words.

“It was suicide.”

Never have I begun a conversation so appallingly.

“Forgive me,” I gasp swiftly.

My apology is too paltry to fill the enormous hole I’ve just dug. The audience see what I see: Goldin is shocked – even disgusted – by my ignorance and insensitivity. This, I realise, is going to be a car crash.

It’s a Friday afternoon in May, 2015, and I’m lying on my bed in a Lyon hotel room when my phone rings. The call itself isn’t a surprise, but its timing is.

I’m in the city to attend the European Lab conference, an intellectual, daytime flipside to Nuits Sonores, its decadent, night-time, techno-flavoured brother. I’ve visited for the last three years, and this trip’s purpose is to moderate a panel in which four individuals discuss ‘The Next Cultural Decade’. At the same time as this proposal was made, I was invited, rather flatteringly – though also more intimidatingly, given the size of the anticipated audience – to host the conference’s closing interview. It’s due to feature Nan Goldin, the legendary photographer who documented New York’s demi-monde during the years when AIDS began to devastate the community around her. I’d visited a retrospective exhibition of hers some years ago, but in accepting the job knew full well that I’d need to spend time in careful research. Beyond what I’d seen that afternoon, and a dim awareness of her reputation, my knowledge of her achievements was limited. This would be a good reason to learn more.

My confidence in my ability to handle a notoriously temperamental artist was in no way reinforced by a story related to me shortly afterwards. A journalist colleague recalled how, after meeting her on behalf of a notable magazine, he’d been abandoned by Goldin mid-interview. Unhappy with the line of questioning, she’d left the room, never to return. Despite this, I remained excited at the prospect of a meeting with someone whose intimate work has done so much to change the artistic landscape. I can’t deny, however, that I was relieved when I received an update from Meryl Laurent, the woman who’d hired me, explaining that Goldin had decided to deliver a lecture instead. Some things are best left unaccomplished.

A few weeks before the conference, I received another message. This one asked whether I’d mind the organisers keeping me on standby. There was, I learned, a chance Goldin might change her mind. Sure, I said, but don’t dump it on me last minute. Tell me on Thursday afternoon, before the Friday evening event. Any later could present problems. If it’s embarrassing for me, I pointed out, you can be sure it’ll be embarrassing for you.

Yet here I am, at 4pm, and Goldin is due on stage in two hours. Meryl, who’s clearly uncomfortable about the short notice, announces that she needs someone to introduce a screening of Goldin’s The Ballad Of Sexual Dependency, which in truth I’ve never watched from start to end, but which Goldin has ruled will take up most of the hour she’s due on stage. Just a couple of minutes to contextualise it will be enough, Meryl assures me, so I accept the assignment, but Meryl’s not finished. It turns out this isn’t the half of it: she may need me to interview Goldin after all. I end the conversation swiftly to ensure I have at least a little time to prepare.

I find a ten-minute conversation with Goldin on YouTube. After frantically writing down some of her key statements, I hunt out the pocket-sized hardback I’d borrowed off an ex-girlfriend precisely for this reason. I skim through the introduction, scribbling further notes, and afterwards locate an online version of The Ballad… to confirm it’s the visceral but tender slide show – soundtracked appropriately and affectionately by the likes of The Velvet Underground, Klaus Nomi and Maria Callas – that I’d come across at her Berlin retrospective, before typing the first lines of my opening speech.

“Ladies and gentlemen… Quite honestly – since honesty is a key theme for what will happen over the next hour – I’m not worthy to be up here introducing European Lab’s closing conference…”

Bona fide honesty, of course, would in fact insist that I admit I’m not qualified to be up on stage. In fact, I’m not even ready to be up on stage. I’ve got scarcely more time than it takes to develop a Polaroid to learn everything I can about Nan Goldin. So I employ another gentle euphemism in my next sentence as I address her performance the previous night in the surprisingly forbidding surroundings of Lyon’s Opera House. There, she’d joined experimental musical collective Soundwalk for a show called A Memoir Of Disintegration, reading texts by her late friend, David Wojnarowicz, as his films were projected behind.

“Those of you who were present last night for Soundwalk Collective’s memorable collaboration,” I type, “will already be aware that her work is uncompromising and unafraid…”

‘Memorable’ is a diplomatic choice of word. Though it had, at times, been dramatic, the event had also been a largely bleak experience, one made grimmer by repeated, blurry black and white footage of a figure dangling by a rope from a bridge. Afterwards, as a bunch of conference attendees congregated outside, one legitimate, albeit light-hearted, phrase kept coming up: “That was a bummer”. Tonight, I realise, I’ll need to frame things differently.

I complete my introduction, wishing I could smoke while I think of further questions. Soon it’s 5pm, so I hurry over to the conference centre, where, as Meryl approves my introduction, we wait for Goldin and her assistant to arrive. Then we wait some more. And then we wait a little longer.

It’s 6pm now, and we’re pacing the lobby nervously. The conference hall is packed, the crowd restless. I’ve not had the headspace to draw up extra questions, and I can’t believe anyone would leave it this late to decide they need a host, so it seems futile to make the effort anyway. A message arrives from her assistant saying they’re on their way from their hotel five minutes walk away, but after a while there’s still no sign of them. It’s approaching 6.15.

Suddenly, grasping her radio and prodding an earpiece, Meryl leaps to her feet. She rushes from the Hotel De Region’s main entrance through the long, cavernous foyer towards the conference hall. I run after her, watching in confusion as she retreats into an elevator, shouting as its doors close about how I should “speak to Raymond with the curly hair”. Perplexed, I head into the auditorium and track down “Raymond with the curly hair”, who tells me to get ready. For what? I ask. Has Nan arrived? No, he admits, but the film is here and it’s time to start. Am I interviewing her afterwards? I persist. He simply motions me towards the stage.

Overhead, beamed onto a big screen, a video explains the live translation systems, and people put on headphones to listen to the interpreters. A microphone is passed my way, and, as the presentation ends, I step out in front of the audience. After my brief, muted mention of the Soundwalk performance, I try briefly to contextualise Goldin’s work with a little puff for those few who know even less about her than I.

“Many of you who weren’t at the Opera will no doubt already be aware of Goldin’s ground-breaking and eye-opening work as a photographer. Her ability to capture friendship and intimacy since she began documenting the lives of her friends in the early 1970s has proven to be deeply influential, and her articulacy about how she operates, and why she has chosen to work the way she has, has been exceptional. Her pictures have touched countless people over the intervening years since she was first introduced to the camera in the late 1960s – and since her first show in 1973 – to the degree that I’m honestly not sure I’m aware of any contemporary photographer whose work is discussed more by people I know.”

This last statement is indeed true, though that may be largely because I’m undereducated about photography. But Goldin is indeed mentioned in tones of awe by my art-loving associates, and I proceed by giving an example.

“I’m reminded especially of a friend in Norway who, upon learning that tickets to a talk Nan was giving had sold out, broke down in tears. Several weeks later, when she met Nan at a signing in Oslo in advance of that talk, she told her why she was unable to attend, and Nan promptly put her on the guest list. This provoked a second round of tears. That’s how important Nan’s work has become to those who know and love it.

“We are therefore privileged this evening,” I conclude, “to have the opportunity, in the presence of its creator” – conceivably, I think wryly – “to watch The Ballad Of Sexual Dependency, something that Nan herself has referred to as ‘the defining work of my life’. Also available as a book, it illustrates, in an unusually autobiographical manner, the New York world in which Nan circulated between 1979 and 1986, a world that would be torn apart by the AIDS virus, and yet one which was nonetheless as full of life as one could ever hope. What you are about to see helped redefine photography, opening the door for a form of so-called confessional art from which it has been impossible to return. Afterwards, Nan will answer questions about her work. Ladies & Gentlemen, Nan Goldin and The Ballad Of Sexual Dependency…”

Contains NSFW images

Given the circumstances, it’s not a bad speech, and the warm applause that greets it confirms this, though obviously it’s aimed at Goldin. But whether Nan will actually answer questions afterwards remains a mystery. I’m not sure anyone has any idea. In truth, I’m not certain anyone actually believes she’s going to turn up. Nonetheless, as the lights are dimmed, and after finding a seat to watch the film, I pull out my notes and, from time to time – just in case – add to them, inspired by what I’m seeing. Throughout the 45 minute film, though, most of my thoughts are centred upon one thing, and one thing alone: am I interviewing her or not? I decide to text Meryl.

“As soon as you know what’s happening, let me know. I can come and meet you.”

“I’m outside smoking,” she replies.

Despite admiring her French nonchalance, I message her again twitchily.

“Shall I join you or just keep watching and preparing questions?”

“I think she will be OK, but… Keep you posted.”

“Worse than Beyoncé,” she adds soon afterwards.

After three quarters of an hour, the lights go up. There’s no sign of Nan. I send Meryl, from whom I’ve heard nothing more, another text: “It’s over.” An awkward silence hangs in the room like a fug of marsh gas. Everyone stares at the stage, where its sofa, armchair and three wicker chairs taunt us with their emptiness. Someone really needs to talk to the audience. I wonder if it should be me. But even “Raymond with the curly hair” doesn’t know what’s happening, so what can I possibly say? I sneak out to find Meryl.

The foyer is almost deserted, so I stroll towards the main entrance. Encountering no one, I turn back and see Meryl’s colleague, Charlotte, beckoning me. As I stroll towards her, I notice the panic in her face and start jogging instead.

“Nan’s waiting for you on stage!” she announces frantically. “She’s about to go back to the hotel!”

There’s no time to reply. I heave open a door, swoop down the aisle, grab my notes hurriedly from the seat where I left them and leap onto the stage. Goldin sits waiting, hunched in her chair, her face shrouded in scepticism. I’m unaware that, as she’d earlier settled in to wait for me – a time variously described afterwards as between 30 seconds and five minutes, but universally as a painful, interminable age – she’d asked if anyone in the audience would like to pose a question. No one had dared. As she’d shrugged her shoulders, I’d arrived in the auditorium, comically dishevelled. Within a minute, following the revelation about her sister, I’d wish I’d stayed outside.

After Goldin’s mortifying opening words, I try hard to compose myself, ploughing on with something I’ve read about how her family reacted to what I now know was her sister’s death, asking whether people these days handle such situations better. Goldin mumbles simply that she’s not going to answer this question. With her microphone still redundant in front of her, few people catch her words, but I can feel my face reddening further. I try a different tack.

“I believe that a lot of your work is a work in progress. I’m wondering if you could elaborate on what you mean by this concept?”

She mutters something again, and this time I tentatively pass her the microphone.

“It’s never really finished,” she says. “The piece you just saw – The Ballad – I started working on really seriously in 1981, and I just made a new one for a museum who’s buying it. I’m incapable of selling the same slideshow twice.”

She smiles, just momentarily.

“I just constantly want to refine it so that it’s clearer to people what I’m trying to say. And there’s some versions that are really sweet, and some that are really tough, and when I was showing it all the time, I would change it every few months. Depending upon how I was feeling, it could be extremely nasty towards men” – she snorts, almost inaudibly – “and sometimes it would be sweet and tender. There’s a basis to it, and I’m just changing some images now. It’s probably the toughest version I’ve made.”

I recall vivid, saturated pictures of friends in their apartments, lying on beds, some of them post-coitus, some of them even mid-coitus; snapshots of bruised faces, drug-emaciated bodies, drag queens, parties, wakes and empty apartments, the very essence of life and death. Many of her subjects never made it beyond the 1980s. I explain how I saw a version in Berlin a number of years ago.

“No,” she replies firmly.

I look at her, confused.

“I just finished it two weeks ago.”

“Ah,” I reply quickly. “This version. But there was a version at the C/O Gallery in Berlin, and I don’t recall that being quite as stark and sad as this one, particularly the end.”

“Which one was this?” she asks.

“The one at C/O Gallery,” I repeat.

“No, no,” she says irritably. “This one.”

She looks to the side of stage.

“The MOMA? OK.”

She turns back to me expectantly. I realise I haven’t asked a question.

“This one I found particularly bleak towards the end,” I reiterate.

“I thought it was a kind of happy one,” she drawls.

I laugh. It feels good to let out a little tension. She glances up and smiles at me, this time surprisingly sweetly. This is briefly reassuring, but the truth is I am way, way out of my depth. I can hardly remember what I saw this afternoon, let alone a slideshow I watched back in 2009.

“I find a lot of it very, very celebratory,” I fumble, “but the final images…”

“It’s very funny if you get it,” she interrupts me. “I mean, sort of, isn’t it?”

“I think there’s life and humour in a great deal of what you do,” I counter, “but the images of the empty beds followed by the images of the gravestones are very poignant…”

“But that,” she says, stifling a grimace, “was the same in C/O as it was tonight.”

“Did you find that a particularly difficult part to create?” I persist.

She looks at me, bewildered, her head tipping to one side.

“No. Not at all.”

“You don’t feel it’s hard to look at this and remind yourself of what it’s all about? What you’ve lost?”

“Yeah, when I watch it, it’s horrible, because I miss all the people. The images of the gravestones all over the world… I find it ironic that people think that they can stay together even after death.”

She breaks off once again. I’ve got nothing. I reach for my papers and select a new angle. If this one doesn’t get her, our interview’s going to be over in minutes.

“There are people who believe that the taking of photographs is a way of removing their soul,” I venture, “but when I look at your photographs I feel that it’s actually a way of preserving it. I wondered whether the idea of taking these pictures gave people the sense that they were becoming immortal, or whether you had to really struggle to persuade them to let you take pictures like this.”

“That’s nice, the idea of immortal,” she says reflectively, her voice almost drowsy. “I like that. No, these are my friends. These are the people I’ve lived with. So if they didn’t want their picture taken, I didn’t take it. If they wanted something taken out, I took it out. So there wasn’t that kind of struggle. I think I had this Pygmalion complex that I can show people their best parts of themselves, and I can show them how beautiful they are.”

“I lost a friend to suicide in 2001,” I suddenly confide, warmed by her response, “and I received a fax afterwards from a musician with whom I worked in which he said to me, ‘Try not to think of your friend as gone; think of him as missing.’ Is that something that maybe resonates with you?”

“Well,” she sighs, letting the silence ring on a while. “They’re missing for a long time.”

I nod in sympathy.

“My best friend just died,” she adds.

I’m taken aback by this disclosure. “I’m sorry to hear that” is all I can manage.

“Five months ago.”

She examines her fingernails.

“It’s a particularly bleak year. Three of my best friends died September, two of them on the same day. My best friend since childhood.”

She looks suddenly very vulnerable.

“It doesn’t get easier, does it?” I commiserate sincerely.

“No,” she states with conviction. “It gets worse. It gets much worse.”

“Are you inclined to take pictures when things like this happen? Does it drive you to take more shots?”

“I’m not really a photographer any more,” she tells me. “I haven’t thought of myself as a photographer in years. I think of myself, I guess, as an artist.”

She huffs self-deprecatingly.

“But I use photography to make slide shows, like films, and big grids of lots of images together. And I draw. A little. That’s sort of my secret passion, drawing, though I really want to make films, and these are the films I’ve been making all these years. The good thing about making films out of stills is that you can constantly re-edit them, whereas a film shot on stock, it’s not so easy, I guess. But lately I’ve been taking real photographs – I don’t know why – but doing shootings with people for a book that’s due next week… that isn’t ready. At all.”

Her eyes widen theatrically.

“But it’s interesting that you talk about sainthood,” she continues, and even if that’s not quite where I’d been headed, the words bolster me, “because it’s my friends in relation to saints. And paintings. It comes from my last work for the Louvre called Scopophilia. You know about that?”

I shake my head, embarrassed.

“You’re forgiven,” she smirks, rolling back in her chair. I tell her that’s a relief.

“It’s the last piece I made,” she explains, “and it’s very important to me. I’ve done a lot of slideshows, but this one I showed today and Scopophilia are the two most important. The Louvre gave me carte blanche, and so I was able to go there every Tuesday, when there was no one there, and photograph anything I wanted. I did it for about eight months, and it was heaven, absolute heaven. And Peter Hujar, who’s a great photographer, taught me the word ‘scopophilia’, meaning the absolute pleasure in looking. Not as a sexual term, but as complete fulfilment. And that’s what I experienced when I was alone there. It was kind of a euphoria. So the piece is called Scopophilia, and a friend of mine who worked on it… I have thousands and thousands of slides that aren’t in any way organised, and he went back into these boxes from the 80s that say ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘maybe’ on the top of the little slide box, and he dug through all that stuff. And I made the correlation between the faces of the paintings and my friends. It’s with someone singing Ovid’s Metamorphosis over it in Latin. It’s a beautiful piece. “

Still intrigued by her revelation that she doesn’t think of herself as a photographer, I ask whether she ever considered herself an ‘accidental’ artist, somebody who started taking pictures and then realised that what they were doing was way more profound than perhaps they initially realised.

“I think I was always an ‘accidental’ photographer,” she corrects me after a short pause. “I don’t think I ever wanted to be a photographer. I just wanted to be a filmmaker. But when I started I didn’t know about art photography. It’s a long time ago. Before any of you were born.”

Her tone, I notice, is tinged with regret.

“So I wanted to be a fashion photographer. I was living with a group of queens who were so beautiful, and I wanted to put them on the cover of Vogue, which wasn’t happening at that time. So those were my first pictures.”

“I think you did these for your student magazine?”

She looks at me strangely.

“Am I correct?

She indicates sternly that I’m not. I shrink, much as I did seconds after I first sat down.

“I didn’t go to school! Well, I went to what’s called a hippy free school, based on Summer Hill, if you know what that is?”

Every time she asks a question like this I feel ashamed of my philistinism.

“It was a form of education started by a man in England named AS Neill, and there are no classes. There was no student magazine.”

“Well, what I read was that some of your earliest photography was based around this idea that you had wanted to take fashion photography, but what you did then was definitively ‘Nan Goldin’. It wasn’t fashion photography.”

“No. It didn’t quite fit.”

“In what way didn’t it fit?”

“I only care about content. Actually, now these pictures are really appreciated. I started when I was 15, so yeah, I became the school photographer. We didn’t have a newspaper. What we did is we went to the movies three times a week, so that’s what I know best.”

Anticipating another dead end, I switch topics again.

“Have you ever thought of your work as being deliberately confrontational?”

“No. I am confrontational. That’s the kind of person I am. I don’t think of my work as anything but an extension of myself.”

“You’ve definitely said before that you think of the camera as an extension of your arm.”

She nods, awaiting further prodding.

“Personally,” I elaborate, “I come from a nice little cosy, English, middle class upbringing, and I do find your photography quite confrontational, if not in a sensationalist fashion. You’ve said in the past that these people were not outsiders, and you were not an outsider. This was a real life.”

“It still is,” she scolds me. “I mean, I’m still alive. Sorry. There’s people that think that I’m dead, but I’m not! So we’re talking about me in the present tense. It’s not just the past tense.”

She checks I’ve grasped her meaning.

“I guess if you grew up in a nice little cosy family you’d probably find it difficult, but there’s a big mistake that it’s about a certain milieu. It’s about human relations, and particularly about male-female relations, and why they’re difficult. And I’ve had 70-year-old, 80-year-old couples in the north of Finland say, ‘That’s about us’, who really understood it. It was never about the marginalised Lower East Side and all that. We weren’t marginalised from anything. We were ourselves. We weren’t worried about how other people viewed us.”

I ask whether people consider it less ‘outsider’ these days because she’s allowed them to see things that perhaps they never would have seen.

“And they never would have talked about,” she points out. “But I think it’s always been important to me to make the private public. To me that’s a political act, and the only way the world can – anything can – change, is if people talk about it.”

A richer seam of understanding seems to be emerging. In fact, watching video footage of the interview months later, I’ll recognise that, despite the frenzied confusion I was enduring, I’m handling things by now about as well as can be hoped. Up on that stage, I still feel like I’m trying to clamber out of a trench, but I struggle on, sweat pooling at my beltline, as I question whether we remain a conservative, repressed society. That, she says, is a difficult question, and my heart swells with delight at the notion that I’ve succeeded in engaging her. I can’t disguise the fact I want to win her over.

“I think there’s a lot of class and gender studies,” she continues, “and to me that’s not really what it’s about, but at least people are talking about these things. It’s become academic, almost. It crossed over, but in this very academic way, and a kind of commercial way also, like television. But I don’t know how much that’s really changed the way people behave and treat each other. I think it’s better, for instance, for drag queens now than when I was living with them.”

The audience, I notice, is very quiet. It’s hard to tell whether this is because they’re attentive or still cringing at how the interview began. I resist an urge to look out at them.

“One thing I found fascinating about The Ballad… was your use of music,” I announce, guiding things towards an area with which I’m more familiar. “This might be an unusual thing to point out, but the sound itself is slightly muffled, as though you were listening to it on an 80s home stereo. Was it a conscious decision to create that sensation?”

She reminds me that the soundtrack was compiled in the 1980s, and how the date, 1987, is noted in the credits. When I suggest she could have updated the music each time she revised the slideshow, I sound merely petulant. So I ask whether she’s ever frustrated how people focus on a work that’s now thirty years old, rather than, perhaps, Scopophilia.

“Well, I wasn’t allowed to publish a book for eleven years thanks to a contract.”

I raise my eyebrows.

“I didn’t know about that. I assume that’s something you can’t discuss.”

“I can,” she nods. “Oh, no. I can’t. I signed a confidentiality agreement. I got out of it with a buyout book about kids that came out last year. So that’s one reason that people don’t know much about my work in the last decade, because I wasn’t allowed to put out books.”

“Has that perhaps added to the value of what you do? There’s a lot of people I know who think of you as perhaps the definitive…”

“The what?!” she interrupts.

“Definitive… the definitive photographer and documenter of the last 40, 50 years.”

“They consider me what?”

I don’t really understand why she’s struggling with the question. I smile amiably at her, but, adding to my agitation, my phone has started vibrating in my pocket. I wonder whether it’s Meryl sending me instructions as to how much longer she wants me to talk.

“A definitive documenter.” I repeat, flustered, almost spelling out the words, “of a great deal of the world, or certainly your world.”

“Well, I like to think I made a sea-change in photography, in that when The Ballad came out there hadn’t been anything like that, except Larry Clark’s book, Tulsa, which had been about fifteen years earlier, and had not had much circulation, and was actually good photographs…” She looks bashfully at me to monitor my reaction before, satisfied, continuing. “I never cared too much about ‘good’ photographs.”

I’d noticed this, in a sense, when examining my ex-girlfriend’s book, but our conversation today has only made her work seem more powerful. Her comment also provides a new avenue to pursue: it had struck me earlier that some of the pictures had the same instant, time-freezing quality that digital cameras now allow, which in turn made me wonder whether there’s any place for Goldin in a world where everyone’s a photographer. I ask her why she refuses to work with the format.

“I’ve tried, but it’s beyond me,” she says. “I don’t know how to use digital. I’m not computer savvy at all. I’m not fond of digital photography. I think one of the great problems with the world now is the lack of any consensus that anything is real. There’s no reason to believe, because everything is so set up, everything is so manipulated, and that’s a horror for people who grew up before that time. It’s a horror. It’s not about my reality. I think it’s disconnected from any truth. It’s all made up, basically. And that’s really, really disturbing.”

I persevere with my original premise, my eyes briefly looking up towards the clock on the wall at the back of the hall. I suggest that digital photography allows us all to pretend we’re like her, taking intimate pictures any time we want, but that, nonetheless, we exercise more self-censorship nowadays, deleting images, worrying about what others might think or how they may react.

“That’s something that doesn’t seem to have bothered you,” I add. “You said that you deleted pictures – you gave people the option – but I get the sense that there was a great deal less self-censorship going on in your work…”

“I didn’t delete them,” she states decisively, “because there was no ‘Delete’ button in analogue photography. I just put them in boxes, but when I was in art school for a while, I used to think that if you didn’t get 35 good pictures out of 36 you weren’t doing well. And now I think if you get five good pictures a year, you’re doing… Yeah, it changes as you get older. With digital and selfies, there’s way too many pictures in the world! I always felt that the important pictures are the ones that you remember, and how many images do we remember?”

I wonder aloud whether the fact that people feel they have to document every moment in their lives prevents them from enjoying themselves.

“I was able to enjoy it and record it at the same time,” she says. “I hope some of them can. But I don’t know anything about any of them. I don’t know who this ‘Kim’ [Kardashian] person is! She’s the most famous person in the world now. I stay away from popular culture. I always did.”

“Has that become a lot harder?”

“No,” she replies, apparently oblivious to the fact that I’m now discreetly trying to extract my furiously vibrating phone from my pocket. “It’s easy. You don’t have to read Twitter. You don’t have to go on Facebook. You have a choice.”

“You say that,” I say, squirming as I’m confronted by the irony of nothing but a series of unnecessary notifications from the official Nuits Sonores app, “but if I can speak personally, I moved to Germany 11 years ago partially to get away from the white noise that I felt existed in a culture where I could constantly understand what was going on. I moved away to be in a world where, if there was a headline in a newspaper, I didn’t necessarily understand it. I zoned it out. But you find that very easy anyway, just to shut off…”

“No, but I live between Berlin and Paris, and I don’t speak any language but English. So I put myself in a bubble easily.”

“So you can identify with what I was just saying?”

“Exactly!”

Common ground at last. I lean back, though my relaxed appearance is merely a display. Niggling me constantly, at the back of my mind, is the knowledge that I have no idea at all how long we’re meant to be up here, and Meryl’s evidently not going to advise me. I turn to the distressing images of victims of violence in The Ballad, and suggest that the conspicuous defiance captured in these pictures was further enabled by Goldin’s decision to photograph her subjects. There’s a long pause as she weighs up her response.

“The women I recorded were already defiant,” she finally announces. “A lot of the pictures of women beaten up are myself, and I’m definitely defiant. I always was, even as a kid. Somebody once said to me, ‘You were born with a feminist heart.’ I think every woman should by nature be a feminist. I don’t know about ‘should’, but I would hope that every woman, by nature, has that strength and self-worth.”

“But when you were taking those photographs of yourself and friends, to me what it seems to be saying is, ‘I am not ashamed’.”

Realising the implications of what I’ve just said, I add, “which is not the ‘right’ reaction…”

Goldin doesn’t let me finish.

“How do you show the world that you’re not ashamed if you’re not ashamed to begin with? See what I’m saying?”

“What I’m trying to get at,” I say, sticking to my guns, but painfully aware of my point’s delicate nuances, “is whether you negated the sense of shame that society might perhaps have anticipated you’d feel – that you’d been on the receiving end, so to speak.”

“Well, I was brought up in a society in which guilt and shame were served for dinner, so we all come from that, and most of the West comes from that in some variation. I remember where I was standing, and what I was wearing, when I decided there was nothing my brothers could do that I couldn’t do, that I wouldn’t let anybody decide that for me. And when my sister killed herself, and everybody in the family was guilty and taking credit, I said, ‘She did it.’ I was eleven, and I said, ‘That’s an autonomous act. Allow her some autonomy.’ From childhood, I kind of innately understood these things. So I don’t think that. Those pictures weren’t taken to rebel against anything. They were taken out of love. The people I loved I photographed, and The Ballad is painful to me because I’ve lost so many of them. About ten of the main characters are dead from AIDS or suicide. Mostly AIDS. At least ten of them.”

There’s something about the compassionate nature with which she says this that suggests she finally recognises my limited knowledge of her work doesn’t derive from any lack of love for it. I feel an urge to underline my admiration.

“A word I’ve often seen associated with your work is ‘unflinching’. It strikes me that you’re not built to flinch anyway.”

“I don’t know,” she says, wriggling in her chair. “You could probably make me flinch.”

“I think you’re more likely to make me flinch,” I confess jovially.

“Come on,” she giggles. “Try.”

Charmed though I am, I decline the opportunity. Instead I ask whether she felt her work was about trying to find beauty in the everyday, or simply recording it.

“Like I said, I have this Pygmalion thing about helping people become who they really are. I think I’ve brought out, sexually, about twenty people from the closet, including every class I teach, even at Harvard: at least three people come out during my class. And I’m very proud of that. So when I’m taking a picture, it’s about the person, or it’s about the empty room. It’s not consciously about all these other issues that you’re talking about. That’s in the editing process, perhaps. Then I choose what looks beautiful.”

“I get the sense that you redefine what beauty is. When I look at your pictures I see a kind of magic in them. There’s a real beauty in the way you present these people. They’re so full of life.”

“They’re beautiful,” she replies simply. “I wanted to keep people alive. I used to say that if I photographed somebody enough I would never lose them. But I did.”

Her grief remains conspicuous, so I decide to steer her back to the subject of music, asking what role it plays in her life.

“In my work it’s really important. It’s less so in my life, actually. People have made me aware that I’ll be home all day working without any outside stimuli, and it actually can be much more soothing if you have music on. And we all have soundtracks to our lives, right?”

“Would you be prepared to divulge what your soundtrack might consist of?”

“Right now it’s Soundwalk Collective.”

“Obviously!”

We both laugh. A warmth has begun to surface that even those in the audience, I suspect, have noticed. She mentions a Swedish singer, Joakim Thåström, who’s played with Nick Cave and Blixa Bargeld, as well as Bohren & Der Club Of Gore, Nina Simone and Kurt Weill, adding that she finds it hard to listen to electronic music.

“So we’re not going to see you down at Berghain…” I joke.

“Oh, yeah,” she grins. “I go there sometimes. I like to dance.”

I dare to glance up at the clock again. To my disbelief, it’s 7.40pm. It’s time to wrap this up. Get out while you’re ahead and they may even forget how things got underway.

“Honesty is obviously integral to everything that you do, not only in your work, but also in your life, as far as I can tell.”

“I try,” she says, nodding.

“It definitely made me a little nervous about being up here today,” I reveal playfully. “But honesty is a very personal concept. Do you think that your sense of honesty is different to other people’s?”

“I think everybody’s reality is completely different,” she replies. “I think we all have a different sense of reality. You mean how I define honesty is different to other people?

“I mean, what you think is a lie, I might not think is a lie, and vice versa.”

“What do you think is a lie?”

“Well, if you present photographs like this, I don’t know whether or not you’re being honest.”

“Of course not! With Photoshop, how can you believe anything?”

The audience readies itself for a final showdown.

“But the very act of selecting and choosing the images is in a sense creating a narrative,” I elaborate, “so that means it can’t necessarily be honest.”

“That’s really a big thing of people wanting to try to prove something about me,” she says disapprovingly, “that something’s not true. It’s a game I’m really bored with, I have to say.”

“I’m not trying to do that,” I contend, but she retaliates before I can clarify further.

“You’re not?”

She digs her hands into her jacket pockets and twists to one side, though this time in my direction.

“I just don’t want to hear it any more, frankly,” she tells me bluntly. “It’s not my problem. It’s the people accusing me’s problem. I’m not walking around worrying about how people feel about me any more. I got over that when I was much younger. But I’m just tired of people trying to stump the host, or whatever, trying to find some way to prove that’s something’s set up or not true. If people want to think that, that’s their prerogative…”

“And that,” I proclaim hurriedly to the audience, “is a pretty fabulous way to end. Ladies and gentlemen, Nan Goldin…”

Straight away, she puts the microphone down and starts to rise. As I stand up beside her, she leans in towards to me. I steel myself instinctively, anticipating a severe reprimand.

“That was fun!” she says to my amazement. “I really enjoyed that. And I’d like to know more about your life, I think. We should talk some more…”

With that, she ambles towards the steps at the side of the stage.

Afterwards, Meryl hurries over.

“My hero!” she gasps extravagantly. “What a relief! That was amazing!”

I look at her, baffled, as, excitedly, she tells me how Goldin’s assistant had watched with dread as the early moments of the interview had unravelled. Then, ten minutes in, he’d leant over to her and said, “I think this is going to be OK.” He’d clearly known earlier than I ever did. In fact, I’m still not sure it was.

In my pocket, I’m carrying my ex-girlfriend’s book. I want to get it signed, and I’m intrigued by Goldin’s comment that she’d like to chat further. I follow her cautiously out into the conference hall’s vast atrium, where I find her deep in conversation with a woman in her thirties, who I soon notice is weeping. Goldin leans in towards her, so close that their foreheads are almost touching. From time to time, Goldin takes her hand. I catch only one exchange.

“I know,” Goldin murmurs with unmistakable kindness. “I know. It still hurts me too, so many years later, and it will probably always hurt.”

She squeezes the stranger’s hand one last time. I finally recognise the glazed look I noticed earlier is simply exhaustion. Flanked by her assistant and members of Soundwalk Collective, she begins her journey towards the exit. I grab my opportunity.

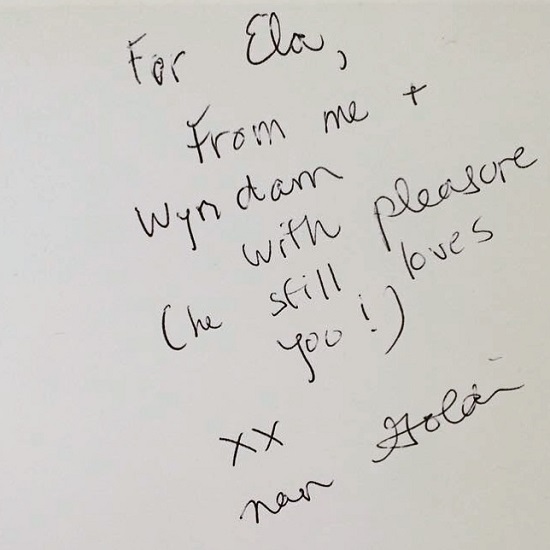

“I wanted to say that I’m sorry if I appeared under-prepared,” I begin, and she smiles with an undeniable, disarming tenderness that suddenly confirms Meryl’s claim. “I wondered if you’d sign this book for my ex-girlfriend?”

Her eyes seem to twinkle at the thought, and she reaches for the book and my pen. Supporting the little hardback in a left hand that appears to be slightly trembling, she tries to scribble something on the title page.

“I don’t think this is going to work,” she says, and for a moment I think she’s finally run out of patience. But it’s the biro’s that’s briefly failed us, and as the ink begins to flow she inscribes a short message.

“You can always cross that bit out,” she says as she passes it back and I read the dedication.

“I hope you don’t mind,” she adds.

“Not at all!” I chuckle sincerely, nonetheless taken aback by her allegation about my feelings. “We’re still good friends. I probably shouldn’t have broken up with her in the first place.”

“Ah,” Goldin sighs with sudden, almost palpable wretchedness. “I did that once. The biggest mistake of my life. I still regret it. I don’t know if I will ever, ever get over that.”

She looks haunted now, an altogether different woman to the fierce, intimidating creature who’d stared me down on stage. I want to tell her it will be OK, but she knows better than I.

“Maybe I’ll see you in Berlin,” I say instead, bidding her farewell.

“That would be nice,” she replies, letting go my hand. I watch her stroll out through sliding doors into Lyon’s indifferent drizzle, my dignity restored. Nan Goldin’s apparently made me a hero. In her own unique fashion, that’s what she’s always done.