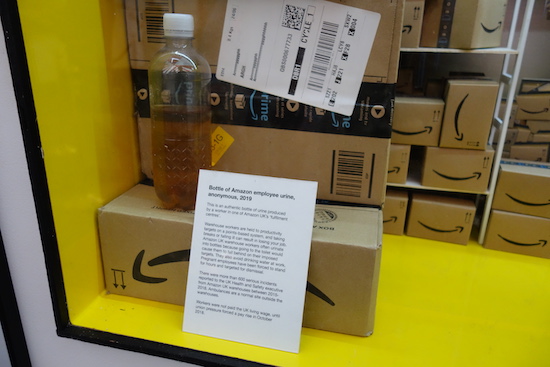

Nestled into the ground floor of a 1960s high street complex in Lewisham is a treasure trove of countercultural delights. The Museum of Neoliberalism is filled with clever and witty takedowns of the financial and political systems that govern our existence. From a genuine bottle of piss from an Amazon worker not permitted a toilet break, to a revolving coronavirus prize table ‘PFI Game’ highlighting cronyism, this tiny delight of a place is crammed with satirical bite.

The museum was founded by the satirical political artist Darren Cullen. He was inspired to start the project on discovering plans for a David Cameron-backed museum celebrating Margaret Thatcher. He met fellow artist Gavin Grindon while working on Banksy’s dystopian theme park Dismaland in 2015 and they decided to work on the project together.

“The more we talked about it the more we realised that in order to understand why Thatcher did what she did you need to understand [former president, General Augusto] Pinochet in Chile and the ideas of Milton Friedman and [Austrian economist and theorist, Friedrich] Hayek and the long-term legacy that has meant every UK prime minister since has subscribed to the same economic ideology,” Cullen explains. “So rather than focusing on her as an individual, if you want to make a museum about Thatcherism you really need to make a museum about Neoliberalism.”

It was four years later, on receiving a commission to build a version of the museum in Brighton that Cullen decided to bring it back to London in its entirety. He set up a Crowdfunder and raised the money to move and install it in the front of his Lewisham studio.

“It feels like a good use of the space. I like the idea of having a leftist critique of neoliberalism installed on the high street,” says Cullen. “This is something that would never exist in any official capacity, so we had to make it ourselves. And the reaction has been amazing. Considering how small the museum is physically, people seem to get a lot out of it.”

A bottle of piss from an Amazon warehouse worker

If an exhibition of anti-capitalist art and artefacts sounds to you like something more suited to a student dorm room than a museum, then consider the following: in the years since the museum was established, we’ve seen the successful implementation of a sort of Universal Basic Income at the height of the pandemic, we’ve seen a wave of strikes, walk-outs and protests targeting transnational corporations like Amazon, Google, and Starbucks; we’ve seen election victories for socialist candidates in Portugal, Peru, and Ecuador (not to mention a fairly near miss for Jeremy Corbyn in the UK in 2017). Meanwhile, recent reports in Forbes magazine about a generation of Millennials growing up to reject corporate jobs and the growth of the anti-work ‘Tangping’ movement in China suggest a burgeoning dissatisfaction among younger people today with business as usual. In addition to this, just recently a victory over Amazon wanting to build on indigenous sacred land in South Africa indicates a shift in priorities for people over profits.

“One of the points we make in the museum is that neoliberalism is essentially class solidarity and organisation – but by the rich. Between 1950 and 1980 there was a period of relatively low income inequality because workers had secured more power for themselves through unions and organisation. In response to that, the ruling classes coalesced around promoting neoliberal ideas that would secure their position by increasing their wealth and power,” says Cullen. “Income inequality is now higher than it has been since 1920 and the less power we have to resist it, the worse it gets. So our power decreases even further.”

A sister project of the museum is the Hell Bus, which Cullen is taking to the Glastonbury festival next year. Revellers will step into a revelatory series of installations drawing attention to the activities of the Shell oil company which, in the face of the climate crisis, has gone on a public relations offensive in an attempt to claw back some profit.

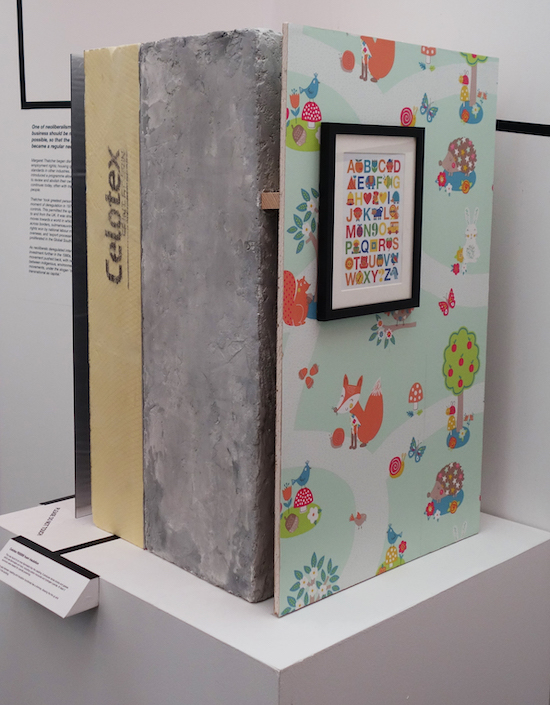

A sample of the flammable cladding used on the Grenfell Tower, London

“The bus is an attempt to draw out the absurdity of greenwashing propaganda so that it’s hard to see a real ad for this shit without laughing. Because whenever an oil company tries to present itself as part of the solution to oil companies, they should be laughed out of the room,” Cullen declares. “The reality is that they’re still exploring for new oil and gas deposits, they’re still opening up new wells, lobbying for fracking and shale oil and new pipes, and just constantly expanding their operations.”

The Hell Bus, currently parked out back of the museum, is a condensed example of what the museum does so well. It takes the ridiculousness of the world’s hypocrisies and sends them up with wit and dissent. Given the potential limits being placed on in-person protest in the UK in the controversial Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, I wonder if subtler forms of dissent – such as art, satire and humour – might become increasingly relevant. Cullen has his doubts. “I think the fact that direct action and disruptive protest are being targeted by legislation shows what the establishment is actually afraid of. They’re not banning political posters because, as much as I wish it was the case, they’re not much of a threat to them,” he warns. But his words come with a disclaimer: “That’s not to say I think my art is pointless. But I think protest art only works in support of activism. It can help bring people into it, it can help communicate ideas, and it can have a morale-boosting effect for the people putting their bodies on the line. It’s part of the struggle, but it’s a supporting role.”

In today’s world, life can seem increasingly homogenous. Everything seems to be for sale. Taking a step off the internet and into the Museum of Neoliberalism may offer a pandora’s box filled with issues of the modern world, but it will also encourage a step back from the bombardment of commercialism.

is open Thursday to Sunday by appointment only