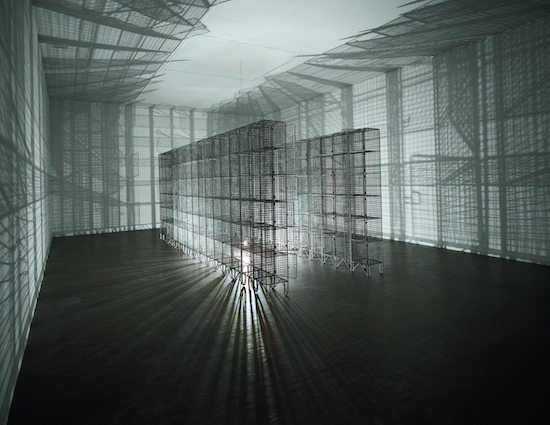

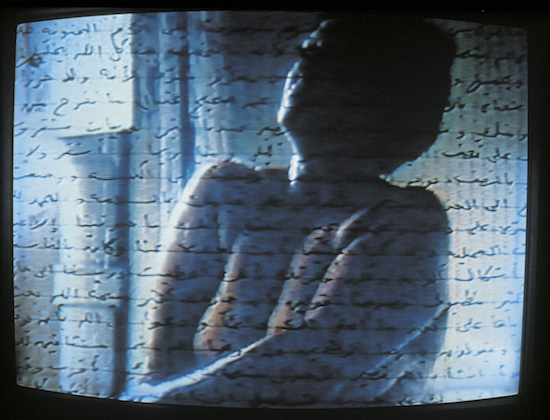

Mona Hatoum. Light Sentence 1992, Galvanised wire mesh lockers, electric motor and light bulb, 198 x 185 x 490, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris: Mnam-CCI / Dist RMN-GP, Photo: Philippe Migeat, © Mona Hatoum

Another day, another bomb attack, air strike or battle in the Middle East. The litany of incidents in far off countries seems to stretch on endlessly, each new tragedy adding to a list that ends up bizarrely anonymous. We forget the names and we neatly tidy the instances under ‘terrorist attack’ or ‘drone strike’ in our mental filing systems. They are subsumed into an orderly category, and then stored away. We no longer have to process the horror.

The sheer regularity of mass losses of life at the hands of fanatics have rendered this type of death part of today’s background noise. The urgent beeps and cataclysmic drum rolls of the BBC News theme tune are almost inevitably followed by a low clipped voice announcing ‘Hundreds dead in bomb attack’ like a brutal jingle.

We’re divorced from the weekly horrors inflicted in parks, train stations, markets and shopping centres; places that we visit every day with not a care in the world, apart from that rude commuter who pushed in front on the Victoria line. We only confront their real and terrible impact when they happen close to home, in London in July 2007, Paris in November 2015, or Brussels in March 2016, when the violence breaks through the categories we’ve built to safeguard our mental space, into new territory.

Tate Modern’s exhibition of Mona Hatoum takes that same distant violence of geopolitical conflict that we hear about every day on the news, and brings it home, into the domestic space and onto the body. Through video performance works, sculptures and installations spread over 14 rooms, she takes the fear that, by rights, should be ever present in our lives. She escorts it into our homes and across the threshold onto our very flesh. Hatoum illuminates the reality of lives like hers – the tension, the pain, the loss and the fear – and makes the daily suffering of other people on the horizons of our world suddenly extremely relevant.

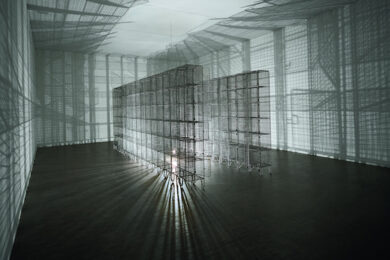

Mona Hatoum, Measures of Distance, 1988, Video, colour and sound, 15 min 30 sec, Tate. Purchased 1999 ©Mona Hatoum

The video piece Measures of Distance (1988) strikes you instantly with the ache of homesickness. Abstract, intimate stills of the artist’s mother in the shower, back in the Hatoum family home in Beirut, are overlaid with Arabic cursive and faint grid lines. The writing comes from the letters that were almost the only form of communication between Hatoum and her mother for around six years, when Hatoum was effectively exiled in Britain as civil war erupted in Lebanon while she was visiting the UK in 1975. You can hardly imagine what it must feel like to be on holiday but know you can’t go home. You’d be trapped in security: safe from the violence as your home ripped itself asunder, but simultaneously stranded abroad with no home to go back to. Suddenly an asylum seeker, rather than a tourist.

Over the top of the images, poignant in their slow mutation, is Hatoum’s voice speaking alternately English and Arabic, talking with her mother and translating the letters she sent over land and sea from war-torn Lebanon. The combination of the soft maternal roundness of doughy arms, the mauve-blue tones of a warm evenings past, and the voices, tinged with sadness, augments the gaping loss of displacement, where a mother-daughter bond is limited to occasional disrupted letters, and war is a troubling mundanity.

Hatoum’s ponderous and tender work causes the focus to tighten like the sudden clench to your innards when panic hits. Even rather bourgeois, everyman pastimes like travelling abroad can suddenly tilt and crash when political conflict breaks out. We never think what’s happening in Syria could happen here, in our lives filled with Netflix binges, tweeting about the predictably awful weather and after work drinks in the pub. What happens when something drastic makes our normality crumble?

The feeling of loss and homesickness segues into something altogether more foreboding with Homebound (2000). A whole room installation like a domestic theatre set, except the sickening buzz of live wires fills your ears: everything is snaked through with wires connecting kitchen chairs to the mattress-less bed frame, and you’re stopped from coming too close by an intimidatingly high wire fence, like the ones surrounding prison camps. The fence forces you to remain at a remove from the unsettling tableau; you are cast as an impartial observer who arrived after the performance had finished and all that’s left is the remainder after some unspeakable brutal act. There’s no-one left to tell you what really happened, or explain how the domestic space suddenly became a place of horror, only the ominous electric hum and the wires that connect everything together indecipherably. Your mind rushes to make sense of what happened, darting from one element to another in what feels almost like panic. This frenetic anxiety is heightened by Grater Divide (2002) and Daybed (2008) in the previous room, where simple household furniture and utensils take on the appearance of torture instruments when blown up to the size of beds or standing screens.

Mona Hatoum, Grater Divide, 2002, Mild steel, 204 x 3.5 cm x variable width, © Photo Iain Dickens, Courtesy White Cube, © Mona Hatoum

Homebound’s name plays with the idea of domestic ties; on the one hand a journey homewards after being away, or being bound to home as in the case of house arrest, that common fate befalling political prisoners like Aung San Suu Kyi or Ai Wei Wei. Platitudes like “There’s no place like home,” are meant to invoke safety and comfort. What does it mean when you’re forced to stay there? What does it mean when you can never go back? What does it mean when the domestic appliances you bought to ease your home life can be used to hurt you? What does it mean when you cannot defend the boundaries of your home against invasion? Hatoum asks all these questions, pointing to the subconscious yet sacrosanct rules of domesticity we hold dear, and the illusory nature of safety when home is an increasingly unstable concept.

It’s not just the domestic space that has boundaries, but the body too. Corps étranger (1994) is a video projection from inside the artist herself, the camera crossing the body threshold in an all-access view of invasive surgery. A queasy journey through the dark tunnels of Hatoum’s body cavity, glistening pink walls surround an abyss extending ahead into the unknowable black. The piece is screened on the floor of a circular cubicle, and the bizarre downwards tilt of the head you are forced into contributes to the feeling of claustrophobia and nausea, like being on the edge of a precipice.

Hatoum picks up the invasive nature of cameras again with Don’t smile, you’re on camera (1980), a video recording of a performance work. Hatoum stands in front of a small audience, approaching different members in turn, brandishing a large handheld camcorder like a sub automatic machine gun. The footage she captures as she lingers on shoes, arms, thighs, is spliced through with x-ray imagery and nude images, giving the impression her video camera had the ability to see through clothes and flesh. Simply watching the piece lends a sort of illicit intimacy – you feel like a voyeur, even though the accompanying text clearly explains that the nudity is not the participants’. Nearly 40 years old, Don’t smile, you’re on camera is still as relevant as ever, standing testament to Hatoum’s prescience in the 1980s of a very 2010s question: what recording, broadcasting and watching our lives is doing to the human psyche.

Mona Hatoum, Hot Spot III, 2009, Stainless steel, neon tube, Photo: Agostino Osio, Courtesy Fondazione Querini Stampalia Onlus, Venice ©Mona Hatoum

Hatoum’s stunning body of work leaves you angry at the intrusions, the invasions and the pain inflicted upon innocents. That anger is laced through with cords of fear; fear that the same pain we neglected to care about when it happened elsewhere is hovering on our horizon. According to Wikipedia, there have been 95 terrorist incidents so far in 2016 and we’ve only just met the six month annual halfway mark. Acts of politically motivated violence have taken place approximately once every three days this year, including the deadliest mass shooting in US history at the LGBT club Pulse in Orlando only a fortnight ago, and yet our lives are still filled with small island mundanities.

Overtly political art can all too often become mawkish, appealing too explicitly to moral codes and asking the viewer to conform to its point of view without nuance or reflection – it tells you how to feel rather than making you feel that way. Hatoum’s work, however, is firmly political but fundamentally powerful. The exhibition builds a sense of horror and injustice, but in a gradual, ambiguous and non-linear way, sending a message without having to resort to shock tactics or PR stunts. At times, Hatoum draws you in close, with works so deeply personal you feel you’re transgressing purely by viewing it, at times pulling away to leave you stranded, alone, and aware of your expendability. Discomfort and body limits are explored from both sides, as Hatoum both subjects herself to trauma and traumatises others. Putting our faith in the strength of institutions, be they political concepts or political parties, is misguided. Whether cameras or enemy forces, whether it’s a nation state, our homes or our bodies, we’re never safe.

Mona Hatoum is at Tate Modern until 21 August