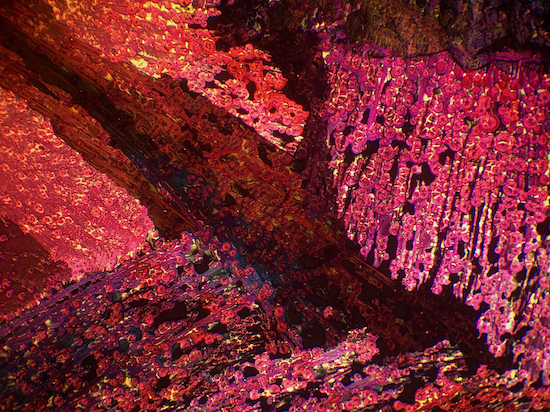

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist Waad AlBawardi, The Hidden Life of Crystals, 2017

Tools of touchscreen communication are objects of desire, hypnosis, and constant anxiety. They are routinely superseded with updated trends and additions that beguile us and nag us into a cycle of renewal and disposal. In our daily lives, we think little of the materials we carry with us. They appear as if by magic, to be carried as loans from their manufactures. Yet, they exist beyond us to be broken down and mined for their raw elements.

On monitors, we can see the documentary footage of The Crystal World (2012), a series of collaborations between Jonathan Kemp, Martin Howse, Ryan Jordan, and participants. An open laboratory that cannibalised junk technology into future fossils, created through processes of heat, high voltages and acidic liquids. Motherboards sit in unidentified liquids and crystallising baths, prompting questions about how these materials are acquired through processes of industrial manufacture, and the scale and environmental impact of such endeavours.

A selection of minerals from the Dorman Museum Geological Collection and the Ruskin Collection is presented as a cabinet of curiosities adjacent to The Crystal World. An unofficial twinning of place and histories of philanthropism that connects Sheffield to Middlesbrough and points to the localities of the exhibition’s own evolution. Ruskin lamented the ruination of crystals carried to the surface by miners, how their geometric formations were scarred by being carried in bags of common materials. Proof if needed that aesthetic beliefs and working conditions can be like oil and water.

The hidden life and dynamics of liquid crystals inform this exhibition co-curated by MIMA’s Director Laura Sillars and Angelica Sule from Site Gallery. Revised and expanded for Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art from Site Gallery, Liquid Crystal Display is a multi-faceted structure articulating the intersections of scientific breakthroughs and mineral ecologies embedded within the legacies of artists practices. The potency and life within the vibrating core of the crystal connect with the conceptual leaps its existence has inspired in myth, medicine, and technology. The show is informed by crystallography, media ecologies, and the cataloguing of collections of geological samples, draws from Ruskin’s archives and the pioneering works exploring LCD technology made by Gustav Metzger and Nam June Paik. Donna Haraway’s Crystals, Fabrics and Fields, JG Ballard’s The Crystal World and Esther Leslie’s Liquid Crystals: The Science and Art of a Fluid Form establish and disrupt affinities between the works presented within the exhibition.

Such a constellation of practices and approaches demand a context that is flexible and generous. Crystal Fabric Field, a sculptural display device by Anna Barham, manifests an ecology that holds together the works in the exhibition. This installation underpins and structures the exhibition. It mimics and elaborates the geometric structures of naturally growing crystals as repeating patterns and behaviour sets. Its yellow powder coated brackets are installed as recurring forms, bolted together to make connections that host sheets of MDF and polycarbonate. Structures informed by the behaviour of ice, emerald, and quartz. The presence of the brackets sparks curiosity then realisation, they punctuate and are inscribed with grammatical marks creating sentences within which the exhibition is articulated.

The exhibition finds its beginning with the echoes and ur-forms present in Shimibuku’s work Oldest and Newest Tools of Human Beings (2015). Held within vitrines is a set of defunct iPhones and iPads. These objects, lifeless as pebbles without their charge, are placed together with prehistoric stone tools. The work is a congruous act, which indicates how the shape and function of our present hand-held communication technology have shifted little from the materials we once extracted and fashioned directly from the earth. Arranged together in corresponding sizes, we can recognise both things as items designed to be held, carried, to be essential to life and hard to put down. There is a continuum here from the breaking down and re-excavation of the stone tools used to advance our lives, and the inevitability of our obsolescent technologies returning to the earth.

Minerals and their extraction perpetuate conflict. The trade of coltan, cassiterite, gold ore, and wolframite have evolved systems of exploitation and human rights violations present within our handheld LCD technology. Artists research into the effect of mineral extraction is presented through Conrad Atkinson’s mixed media collages No Compensation (1977). The work documents the twenty-five-year working life of iron ore miner Billy Hunter at a time in which NUM workers were gaining rights in health compensation that were not available to those represented by the General and Municipal Workers’ Union. Here, an individual experience reveals the injustices that are present amongst the gains that have been fought for and won.

Sharing space with this work is Ângela Ferreira’s Stone Free (2012), drawing a connection between the excavations of the South African Cullinan Diamond Mine and the countercultural site of the Chislehurst Caves. The symbolic value of these holes in the earth that play host to power and protest. The location of one of the largest diamonds ever excavated and the place which once hosted performances by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, these two events are connected through the work to speak to each other.

The macro-corporate structures that seduce us with images of the future also end with the micro acts of extraction and labour. This mining of materials – cobalt from Congo, tin from Bolivia – are undertaken by children and adults who work daily in environments hostile to life. The mountain of Cerro Rico was named by its workers as a place “that eats men”. Yet the advertising of communication technology creates narratives of seamless connection and ease, our touchscreens as immersive black lagoons for restless fingers.

The Otolith Group’s 2011 video Anathema unravels our ritual communion with LCD touchscreens. The gestures of global advertising fuse with the behaviours of crystallization disrupting reality into thresholds of liquidity and animated portals. Our belief in a world that we can digitally touch and modify through the language and movement of our hands holds us in thrall. The Otolith Group propose this work as a “prototype for a counter spell”

Such immersion is present in Ann Lislegaard’s two-channel 3D animation Crystal World (after J. G. Ballard) (2006), which strips away the human presence within Ballard’s writing to focus on the abandoned white hotel that emerges vitrified amongst the diseased glitter of ossifying forests. Light blinds, wiping out details with stark polarising shadows. The animation pivots around the crystalline growths that besiege the hotels’ modernist construction in an unearthly brightness. Pools of water liquify and refreeze as echoes of Caspar Friedrich’s painting The Sea of Ice.

In Ballard’s text the protagonist is cursed for attempting to rescue a figure whose body lies in a river bedecked and infested with crystals. This shift in bodily materiality marks a collision between time and anti-time, the attempted rescue causing a rupture that pollutes the book and the actions that take place within it. Dialogue present within Lislegaard’s work explores the consequences and shifts in behaviours, bodies, and perception as they merge with landscape. An invisible protagonist states “what surprises me the most is the extent that I have accepted the transformation”.

These near futures are depicted in Suzanne Treister’s drawings and watercolours Survivor F (2016–ongoing), presented here as archival inkjet prints. Summers of digital dust merge with a telepathic universe. The data cloud becomes total information awareness and algorithmic zones of liquid desire. Our world is one of mystic interstellar communication connecting nodes and apocalypses of post-human cosmology. It is a space where half-remembered information is regurgitated by chatbots with the precision of a book of days.

There is a joy in this disintegration, one shared in the breaking down of 70mm celluloid in Jennifer West’s Spiral of Time Documentary Film (2013). The work draws on the methodical panning back of Eames’ Powers of Ten, Google Maps searches, documentation checkpoints in the occupied territories and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. The film floated in the dead sea, was immersed in mud in West’s studio for five years then dragged across on the site of Smithson’s earthwork. The resultant work, photographed and transferred to digital HD, is ecstatic labour made through collaboration and open exchange as an exploration of the materiality and poetics of layers of minerals.

The myths, realities and futures of Liquid Crystal Display are conversant with the geo-political issues of mineral extraction present within Tees Valley, whose histories of mining for alum, ironstone, jet, anhydrite, potash, and salt created a scale of manufacture whose presence still inspires awe. Here these dialogues demand expansion. There is a deftness and humanity in a space for art that can make itself a home for hyperlocal conversations; for them to be shared and engaged in all of their commonalities and uniqueness as direct collaboration between the public and artists. MIMA’s Summer exhibition Fragile Earth: seeds, weeds, plastic crust continues to build a space that lessens the distance between viewers and creative practices so that both can engage with the specific character of the region and its emerging future ecologies through the creation of mutual knowledge.

Liquid Crystal Display is at Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art until 16 June 2019. Fragile Earth: seeds, weeds, plastic crust runs from 28 June – 29 September 2019