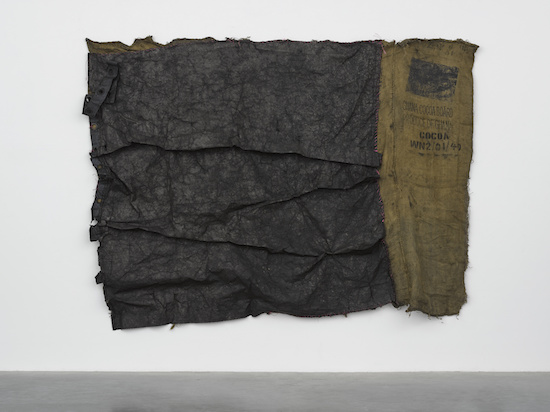

Ibrahim Mahama, DAMONGO COCOA, 2017, scrap metal tarpaulin on charcoal jute sacks, © the artist. Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby)

Memory is slippery. It falters, it mistakes, it invents. And not only do we grapple with our own personal malfunctioning memory, but also the shared cultural, national, and historical memories we both inherit and inform. So, the mutability of memory could be an interesting theme for a group exhibition – especially one which includes work by notables such as Gilbert and George, Tracey Emin, and Antony Gormley. Memory Palace, however, which is currently split across the White Cube’s Bermondsey gallery and Mason’s Yard space, falls short. Somewhere along the way, the curators’ own memories betrayed them. They seem to have forgotten to include any concrete relation between the exhibition’s theme and the work shown.

Memory Palace is divided into six subthemes: historical memory, autobiographical memory, ‘traces’, ‘transcription’, collective memory, and sensory memory. Despite autobiographical memory being the first subtheme encountered at the Bermondsey gallery there is, from the get-go, a disparity between theme and work.

Autobiographical memory manifests itself, whether directly or indirectly, in an exceedingly large proportion of work created by artists – so having a gallery room solely dedicated to autobiographical art feels unnecessary. Which is a shame, really, as Raqib Shaw’s Self Portrait in the Studio at Peckham (After Steenwyck the Younger) II – a queer, nightmarish painting delving into the known and unknown with all its vibrant and surprising splendour – is a part of this particular subdivision. Not only does the painting stand out amongst the other work – which includes pieces by Emin and Gilbert and George – but it also feels so much larger, and far more important, than the tenuous theme it’s been attached to.

If the room on autobiographical memory is where the theme begins to lose its sense of identity, the room dedicated to ‘traces’ is where it completely falls apart. The accompanying exhibition guide has this to say on ‘traces’: “We can think of an artwork as a memory of the gestures or actions that produced it: the record of a line, a brushstroke, a thumb in wet clay. In a cast, an impression or a print, a memory is anchored through an indexical relationship with the subject: the artwork and that which it has touched.” The writing overcomplicates a simple subject – a subject so simple it seems undeserving of having its own separate exhibition space.

MONA – the (Australian) Museum of Old and New Art, which is so large it truly is a palace – hands visitors an electronic device which helps identify the art with accessible biographical and contextual descriptions. The reason why I’m bringing up MONA’s devices is because one of the description options that can be chosen is aptly named ‘Art Wank’; a cheeky nod to the overbearing language and rhetoric used in the art world. Often times it seems impenetrable, high-register language accompanies an artwork when the piece doesn’t have merit enough to stand alone and needs to be academicised in order to have importance.

This sentiment can also be applied to exhibitions.

Memory Palace’s accompanying exhibition guide has this to say on the subtheme of ‘traces’: “We can think of an artwork as a memory of the gestures or actions that produced it: the record of a line, a brushstroke, a thumb in wet clay. In a cast, an impression or a print, a memory is anchored through an indexical relationship with the subject: the artwork and that which it has touched.”

The copy in the pamphlet here not only over-academicises, but it also desperately tries to weave an overall narrative together, to make it appear that, yes, there is in fact something these disparate works have in common apart from simply being in the same exhibition.

Raqib Shaw, Self Portrait in the Studio at Peckham (After Steenwyck the Younger) II, 2014-2015, Acrylic liner, enamel and rhinestones on birchwood, 84 x 59 15/16 in. (213.4 x 152.3 cm), © Raqib Shaw. Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby)

Nonetheless, the writing only confuses matters further. Again, this is a shame, as Ibrahim Mahama’s texturally engaging installation DAMONGO COCOA, which makes use of repurposed cocoa jute sacks from Ghana, is lumped into the room dedicated to ‘traces’. As is two human form-related pieces by Antony Gormley – INTO THE LIGHT and SCAFFOLD X – which risk losing their inherent haunting qualities due to the omnipresence of Memory Palace’s garbled theme.

Most of my sympathy, however, is reserved for Virginia Overton’s Untitled (Quartered Cedar), an installation of cedar wood which revels in its materiality. The piece is left at one end of the hallway and on its own, causing baffled passers-by to wonder, a) whether it is indeed a part of the exhibition, and b) what relation it actually has to the exhibition. Overton’s site-responsive installations – and the way in which she goes about creation in a DIY, resourceful way – are often fascinating, but here it feels like nothing more than sad, dejected material.

Overall, I would say Memory Palace is worth a visit. If you can mentally detach yourself from the tenuous theme, the pieces may be enjoyed on a standalone basis. Especially the aforementioned painting by Raqib Shaw, which, considering its psychological, emotional, and aesthetic potency, is a testament to why Shaw is one of the most visually intelligent artists working in Britain today.