“The population decided – out of sheer panic at first – to carry on as if nothing had happened." – W.G. Sebald, The Natural History of Destruction (1999)

Few writers in recent years have had such a profound and clear effect on the visual arts as W.G. Sebald. Perhaps his own use of visual artefacts in his novels allowed the crossover of his dusty, cobweb ideals to seep into the visual arts around him with more ease than the work of other writers, but the natural sense of what could be called the Sebaldian – melancholic memories floating back through the landscape – is clearly and even openly detectable in the work of many modern visual artists.

Melancholia: A Sebald Variation, currently on display at Somerset House in the Inigo Rooms of King’s College London, has taken advantage of both this increasingly large body of inspired work alongside the wealth of paraphernalia already embedded into Sebald’s work; his novels forever treading the line between fact and fiction via real objects, people, and places.

Melancholia is interesting in that it takes a unique starting point – not in one of Sebald’s four major novels as could be anticipated, but in perhaps his most controversial work: the collection of academic essays, The Natural History Of Destruction (1999). The collection caused various controversies, not least for its frustrated tones aimed at German writers of the post-war period who, in Sebald’s view, mostly failed to address the violence suffered by the defeated German civilians in cities such as Dresden and Hamburg in the allied bombing. With Sebald’s predominate themes being the addressing of traumatic memory through the device of accessing them second-hand via characters and their lives, it is unsurprising to find the writer uncomfortable with the supposed silence of that generation of writers. With his academic work even being classed as overly harsh by the likes of Theodor Adorno, it’s even less surprising that the writer took on a critical character not unlike that of Thomas Bernhard, another writer constantly seething in regards to his own country’s past and the population’s relationship towards it.

Melancholia builds on this sense of quiet frustration and weaves Sebald’s ideas through a multimedia set of responses and explorations of similar themes. The overall theme of melancholy, described as essential by Sebald when he suggests that "… the description of the disaster lies in the possibility of overcoming it", is framed in the exhibition by opening with a sparse room housing only Albrecht Dürer’s engraving, Melancholia I (1514). This engraving shows the spirit of melancholia, detailed as surrounded by objects which suggest some scholarly occupation linked to the spirit of the feeling. Again this is quintessentially Sebaldian as he specifically lives the dictum of Robert Burton. In his volume, The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), Burton suggests "He that increaseth wisdom, increaseth sorrow." All of Sebald’s narrators and their acquaintances live by this, either as academics themselves or by their melancholy being heightened by lost memories attained once more through new knowledge.

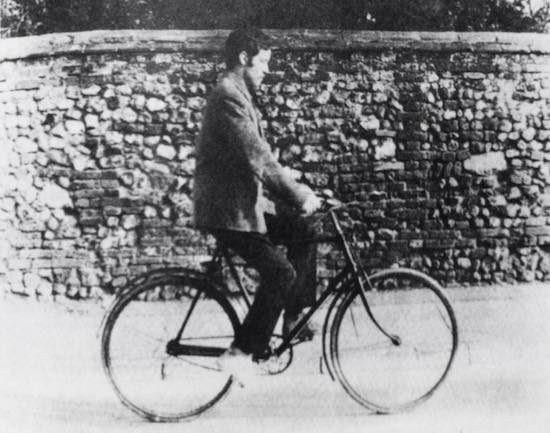

Some of Sebald’s various postcards, photographs, and manuscripts are housed in the exhibition – including an excellent photo of the writer riding a bike, carefree and far from the melancholy of his later self. The work of Tess Jaray, printed designs mixed with quotes from Sebald’s The Rings Of Saturn (1995) and Vertigo (1990), work well and blend into the paraphernalia. Coming as a collaboration from the pair shortly before Sebald died, it is perhaps the only work here explicitly made alongside Sebald.

Tacita Dean has produced a similar pair of new slate works, again using the technique of quotes – this time from Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1611) and The Merry Wives Of Windsor (1602) – to explore the typical melancholy of new contexts. The quotes find a new meaning when set alongside Hans Erich Nossack’s photographs of the bombing of Hamburg and an audio recording from the BBC Home Service recounting the same raid (a recording referenced in one of Sebald’s Natural History essays). The role of recontextualisation is essential to both the exhibition and to Sebald’s work. "I had a father, Mistress Anne;" Shakespeare writes in The Merry Wives of Windsor, "my uncle can tell you good jests of him." The text of the line is put within an image which seems to resemble stormy skies. Shakespeare’s words find a new melancholy, seeming apt for the tragedies befalling Europe 300 years hence.

The texture of Sebald’s writing is often described as being made up particles, dusty, sandy, post-destruction. Melancholia highlights how this ties well to the fragmented, rubble-like quality of his writing. In fact, rubble and broken buildings were the lasting image I took from the exhibition. This sense is captured perfectly in Anselm Kiefer’s Melancholia works, referencing both the scarred post-war German cities that Sebald discussed in his essays and the melancholic figure and designs in Dürer’s engraving.

The exhibition evolves, wandering closer to Sebald’s death through an emphasis on walking in later works. Guido Van der Werve’s Nummer veertien, home (2012) film undertakes a Sebaldian pilgrimage between the church in Warsaw where Frédéric Chopin’s heart lies to the large grave where the rest of the composer’s body lies in the Père-Lachaise graveyard in Paris, whilst Jeremy Wood’s My Ghost (2015) tracks the artist’s own movements around London through the haunted ley-lines walked of the city, reminiscent of Austerlitz (2001), especially, and that character’s lonely wanderings around Liverpool Street and Tower Hamlets graveyard.

Ultimately, Sebald’s death in a car crash in 2001 frames the final works in the exhibition with their country roads and overt references to car crashes. George Shaw’s Study for the Painter on the Road 1 (2015) and Susan Hiller’s The J-Street Project (2002-2005) both evoke country roads, the latter also evoking the memory of the holocaust through its emphasis on Jewish-related street names; the trauma quietly living on. Dexter Dalwood’s The Crash (2008) is the only explicit reference to Sebald’s crash and, though an interesting painting, feels slightly garish as an inclusion considering the quietude of the other destructions in the exhibition.

A more fitting inclusion would have been Jeremy Millar’s A Firework For Sebald (2005), which exhibits a better understanding of the landscape which provided Sebald’s last glimpse of the land. As with the exhibition as a whole, however, there is a sense that this feeling – the sadness creeping through of our constant capabilities of annihilation, Sebald highlighting its depressing role as the spine to our nature – is far from lost forever. The melancholy lives on, though, as Sebald knew, it is still the most effective way to overcome the true disasters of society.

Melancholia: A Sebald Variation is open at the Inigo Rooms at Somerset House until the 10th of December