L’angelo del focolare, 1937 Oliosutela, 114x146cm Collezione privata, Svizzera Classic paintings/Alamy Stock Photo ©Max Ernst by SIAE2022

I’ve got a confession to make: I have a love/hate relationship going on with Milan’s Palazzo Reale. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t usually have particularly hard feelings or soft spots for any other museum. I’ve seen bad or cringe exhibition in my life, clearly, but that did not make me hate nor love any other gallery or museum. Not as intensely, at least. Palazzo Reale is just different. Palazzo Reale, to me at least, has always been synonymous with a certain kind of exhaustion which I both spite and cherish.

Since I’ve been living in Milan, I caught myself returning to it almost mechanically, like the changing seasons or a pallid ritual. Palazzo Reale’s main attraction is usually to drag in town some of the most prestigious names in more or less contemporary art. I saw Modigliani there, strung out from a sleepless night in Bologna; Klimt, after a particularly phoned-in break-up; Warhol, I don’t exactly remember when. And so on. You get the gist. Like clockwork, it has been there ticking away at my late adolescence and early adulthood. I could easily get all riled up and Proustian about the long queues mid-winter and the Duomo gothicly towering behind the rows waiting in line, but I’ll spare you the autofiction.

My love/hate does not exclusively descend from my subjective perspective on it. Not exclusively, at least. The feeling, I believe, is objectively grounded in the experience of Palazzo Reale itself. You see, having such big names exposed in the heart of a city like Milan comes with a heavy burden of expectations. Palazzo Reale has always met the weight with utmost maximalism. Every exhibition, even the most underwhelming, has always been accompanied by this air of expo kitsch. Every one of them is adorned like an enormous event, flock of tourist-proof. This has always been, as far as I’m concerned, a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it takes art out of the art-nuts circlejerks, transforming it into a genuinely mass cultural phenomenon. On the other, it takes art out of its context, transforming it into a genuinely mass cultural phenomenon. Crowded rooms chock full of people are great to take art outside the obnoxious and mostly class-homogenous “underground”, but it can mall-ify it – turning it into a cheap spectacle for the post-shopping hordes.

This ambiguity has been cranked up to eleven in the most recent exhibition at Palazzo Reale, solely dedicated to the surrealist polymath Max Ernst.

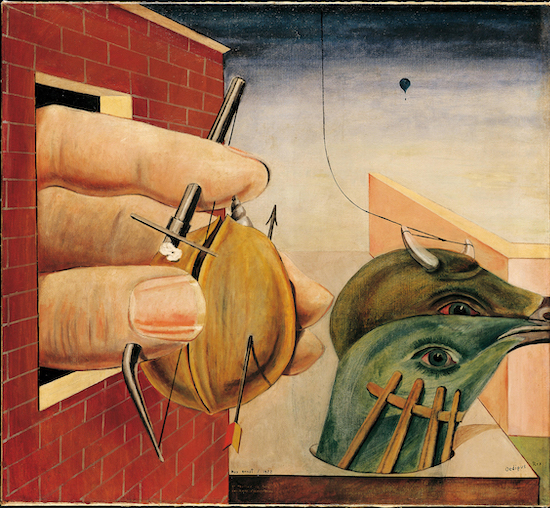

Edipus Rex,1922 Oliosutela, 93x102cm Collezione privata, Svizzera Album/Fine Arts Images/Mondadori Portfolio ©Max Ernst by SIAE2022

The first thing you stumble upon in the stroll through the museum, once past the imposing entry hall and the ticket stand, is the gift shop. A gift shop which, right away, looks surreal in no surrealist way. Stacks of notebooks, cheap Moleskine knockoffs the lot of them, pile up in the middle of it. On the front cover they bear quotes by Ernst himself, and André Breton too. “Surrealism is for all the unconscious” and amidst the tourist crawling by in the morning of the opening of the museum, the irony is not lost on me.

In the second room, where the actual exhibition takes off, you find yourself face to face with two of Ernst’s most disturbing pieces: Oedipus rex and Crucifixion. The former, a mash-up of hands and heads and De Chirico-like architectures. The latter, a grandiose human body, dolled up like Christ, spread open. A woman in her fifty passes me by and with genuine amazement cries out: “Well, that’s terrifying…”

To some, all of this could be alienating. The epitome of art’s loss of aesthetic authenticity in the modern world, or whatever. But the contrary is true. The impact of Ernst’s work is heightened by this very unnatural setting and the most laudable features of the gallery shine brighter beneath this pop light. Engulfed in the neophytes and the uninitiated and the uninterested, Ernst’s art worked different for me. It was genuinely an eye-opening moment, a moment which would have honestly been impossible in a higher, so to speak, or edgier crowd – the sort of crowd that would normally populate anything Ernst related.

For example, the fact, stressed from the very get-go by the curators Martina Mazzotta and Jürgen Pech, that this is the first retrospective in Italy and one of the rare instances in which a bunch of Max Ernst’s works are reunited in the same building hit me like a vindication of history’s repressed memories. The image that is often conveyed in the text on the walls is that of a body of work dismembered in various collections and an artist swallowed by the passing of time, as if the world was trying to etch the existence of Max Ernst from its surface. Much of the first portion is rightfully dedicated, not only to the works of Max Ernst, but also to his posterity: from his various relationships with his artistic zeitgeist to Adolf Hitler walking beneath an Ernst painting during a Nazi display of degenerate art. What good would it have made in any other context? Bathing in people, it feels like a victory against amnesia.

La festa a Seillans,1964 Oliosutela, 130x170cm Centre Pompidou, Paris Musée national d’art moderne/ Centre decréation industrielle

©2022. RMN-GrandPalais/Photographer: Georges Meguerditchian ©Max Ernst by SIAE2022

But setting aside the historiographical concerns, the thing that is most striking about Ernst in this context is the way Ernst’s own works appears in a brand-new light on such a stage. One element that really pops, for instance, is just how punchy his work was on a technical level. Ernst’s constant usage of collage, just to single out one technique out of the many he experimented with, appears in Palazzo Reale as a premonition and subversion of the guerrilla marketing awaiting just outside under the porches of Milan’s heart. These cut-ups, full of figures mangled of context, on the white walls of the museum, look like nothing short of a prophecy – they gain a contemporaneity that I never noticed in any other situation. And the imageries he was obsessed by – the birds, the human body torn to shreds, the jungle – accrue a lot of traction and momentum in the feverish sea of bodies. It’s as if the vivid unconsciousness he was so haunted by could only shine through when actually shared with people whose reaction are somewhat unprepared or unfiltered, and not just passively observed among knowing peers.

But there’s also the downside, of course. Exiting the gallery, I felt exhausted. The crowdedness of it all left me feeling like I’ve been through a terrible sugar rush. The last rooms felt cramped, both with people and artworks, and I longed for some breathing room. It really worked like a big surrealist expo at the end of the day, and I had plenty enough. Was this exhaustion worth it? The obvious answer would be: yes, of course, that’s some great art. But there’s a finer justification, I believe. I honestly prefer my disturbing surrealism to feel like a mass ritual or a One Direction concert, rather than a gallery.

Max Ernst is at the Palazzo Reale, Milan, until 26 February 2023