A squat and sturdy nude makes a striking impression in the Royal Academy’s Matisse in the Studio. Standing nude (1906-7), a female figure thickly outlined and roughly shaded in black, is a far cry from the idealised nudes of classical and Renaissance art whose figurative conventions were shockingly ruptured by modernism. Matisse painted it during the early days of his friendship with Picasso. The Spanish artist, 12 years younger than his companionable rival, was himself about to embark on his brutal masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, partly as a riposte to Matisse’s luxuriant multi-coloured dream-pastoral Le Bonheur de Vivre.

Both Standing Nude and of course Picasso’s ground-breaking proto-Cubist painting of five women in a brothel were reactions to encounters with non-Western art, primarily carved African figures, totems and masks, though the serene stone-carved Iberian heads of ancient Spain also show up in the smooth, mask-like features of three of the women in Les Demoiselles.

Non-Western artefacts offered a radically new way of seeing and remaking the world for avant-garde artists, though Matisse wasn’t alone in barely seeking to distinguish the pieces they appropriated from one culture to another. African sculpture was more or less lumped together, since Primitivism, like Orientalism before it (and after it, too, including Matisse’s parade of Odalisques), was a Western construct. The appreciation went no further than mining the work for its formal qualities rather than delving into matters of cultural significance. The figure who poses as if walking in Standing Nude was actually lifted from a photograph in a soft porn magazine, which Matisse then ‘Africanised’. Here you’ll find the photograph as well as the Congolese Muyombo mask he’d picked up in Paris to show how he loosely interpreted its wide cheekbones, firm, drooping mouth and heavily veiled eyes. You can see how he was attracted to its inscrutable presence.

But this exhibition isn’t just about how Matisse was influenced by ethnographic art. His studio was an eclectic repository for all sorts of objects he used as props: ‘exotic’ crafts and objet d’art, ornate furnishings, pots and cheap coloured glassware. These appear time and again in his work, often as part of an ensemble or in the backdrop as part of a decorative scheme in which the female figure is just one more sensual element. “For me, the subject of a picture and its background have the same value, or, to put it more clearly, there is not a principal feature, only the pattern is important”’ he wrote in an essay in 1935. This ‘all-over’ quality had become an essential aspect of modernism that was about the painted surface itself.

And then there was the personal attachment to these constant studio companions. “Objects which have been of use to me nearly all my life,” he wrote on the back of a photograph showing vases, bowls, coffee pots, china cups, jugs and an African figurine arranged as if all taking part in a big group photo. The photo was taken by Hélène Adant, a cousin of his studio assistant who he’d commissioned to document his studio in Vence. She artfully displayed the objects in groups and occasionally arranged them to enact the compositions of earlier paintings.

Muyombo mask, Pende region, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 19th-early 20th century

Former collection of Henri Matisse. Private collection

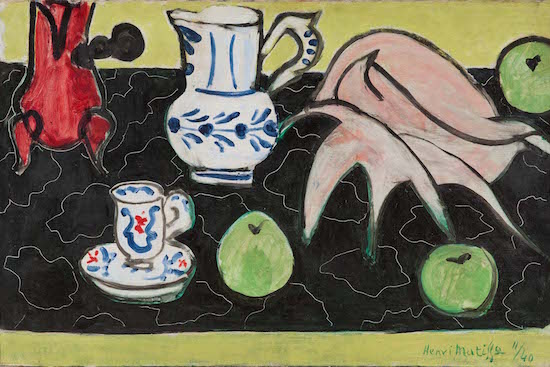

Of these ‘actor-props’ one of his most frequently utilised is an elegant pewter chocolate pot, which was given to him by an artist friend as a wedding gift. The bulbous pot with its three dainty legs and knobbly wooden handle appears numerous times at different ends of his career. In Still Life with Seashell on Black Marble (1940), we see it standing in one corner of the canvas, partially cropped and painted red. With only two drum-stick legs visible, an outline of an exaggerated beaky spout and bottom-heavy body, it’s taken on a comically bird-like form. Confronting it is a large spider conch shell that’s acquired a slightly threatening air, while a china jug, a cup and saucer, and three encircling apples assume the air of impassive bystanders.

One corner of the exhibition is devoted to Matisse’s collections of fabrics and furnishings from North Africa. Some of these are arranged to replicate the seductive, closeted settings of the Odalisque paintings, including Odalisque on a Turkish Chair (1928). Here a pantalooned model unites foreground and background as she expansively fills out the decorative space.

Perhaps more revealing in terms of what were direct influences to his working methods is in the last room. The influence of a nineteenth century panel engraved with Chinese calligraphy – a sixtieth birthday gift from his wife – is evident here in the elegant cut-outs of fronds and flora. What intrigued him about the panel was not the lettering in itself, but the interplay between form and ground, between negative and positive space.

Standing Nude, 1906-7, Tate

But the most fascinating part of this exhibition returns us to his discovery of African art and how this impacted on his early evolution, and ultimately changed the course of modern art. At this point the invisible presence of Picasso acts as a counterpoint. It was Matisse who first introduced Picasso to African art in 1906, having acquired a seated Congolese Vili figure. An unfinished painting by Matisse, from 1906, the year he bought it, shows the figure, realistically rendered, floating in the centre of the canvas.

Picasso was to have a far deeper and more radical engagement with ethnographic art – perhaps, or at least partly, because he was also the younger artist. African art provided him with a breakthrough moment, and it was a relationship that endured. For Matisse it simply forged another way of paring down, of simplifying form, or perhaps responding in a more superficial way. This exhibition doesn’t of course set out to explore that disparity, but often – the Chinese Calligraphy panel being the exception – the objects feel superfluous because his relationship to them feels more like that of an enthusiastic collector. He changed and brilliantly remade what he painted, but largely, in themselves, they didn’t change him. And that feels like a big difference.

Nonetheless, this is a hugely enjoyable exhibition, with some stunning painting. And though it’s an interesting enough encounter with the various objects that filled his studio, they don’t actually add very much.

Matisse in the Studio is at the Royal Academy until 12 November, 2017