Mat-Collishaw, The Grinders Cease, 2018, Installation view, Courtesy The Artist and BlainSouthern. Photo: Trevor Good

The condemned man ate a hearty breakfast we are told; Mat Collishaw isn’t so sure. His show here is called The Grinders Cease – a line from Ecclesiastes suggesting the edentulate. In one of three separate light-locked spaces in his new show he gives us six wall-mounted C-type photographs set in jet black lacquered frames. The ill-lit background of the room is kept as dark as a chamber of horrors. We see plates of food lit carefully with chiaroscuro effects recalling the efforts of the best Dutch Masters. The series is called Last Meal on Death Row, Texas (2011) and this is precisely what it shows.

For Bernard Amos this choice was a plate of unappetizingly off-pink baloney sandwiches, the bread cut into thick slices. The New York Times duly reported that he “gulped twice and gasped once as the lethal drugs began to flow through his body.”

Cornelius Gross went for some fruit – two peaches and an orange, the puckered skin of the latter refulgent in the dim hall.

Martin Vegas had some ghostly white prawns; their dot eyes like so many of the prophetic black spots that cursed R.L. Stevenson’s Blind Pew.

Paul Nuncio’s choice is bathetic – a couple of tacos.

Jonathan Nobles goes for the body and blood of Christ, a small glass of red wine and a communion wafer.

Apart from his preference, you can’t imagine the other men, all about to die, actually getting what molars they have left through these meals. The lay out of each dish seems portentously loaded; like one of Warhol’s electric chairs, their mute import is symbolic of the diners and their fate.

A solitary work in the main hall precedes these grim servings and sets the tone. Columbine (2018) is an image on a LCD screen that takes Albrecht Dürer’s watercolour from 1526 and animates his drawing of a plant as if it were being blown by a light gust of air. The columbine, or granny’s bonnet, is a plant with poisonous seeds and roots that we learn are toxic to the heart. The plant also happens to be the state flower of Colorado and memory doesn’t have to strive too hard to recall the eponymous high school made infamous by a massacre.

Appearances can deceive, a simple artistic credo. Mat Collishaw has long been fascinated by how something that can look so good can in fact be totally rotten.

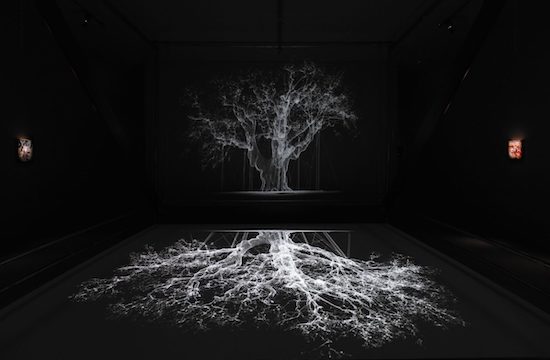

The first of his darkened rooms contains Albion (2017), a projection, the laser-scanned image of the white outline of a tree on a black background. This is reflected from an upright mirror onto the floor space. The tree is sick, dying, propped up by scaffolding.

The tree is a representation of the Major Oak in Sherwood Forest, a hollowed out old beast that has been kept aloft for decades by crutches. The oak as an ancient symbol of England is thus reinterpreted and in this revised version clearly craves help. This is a thing on its last legs in need of clean air; it’s an obvious metaphor for the state of the nation.

Albion suggests that the country is a proud giant in need of real support in its dotage. The inverted image on the floor looks like an anatomical drawing of a lung, the branches as bronchi ever splitting out toward the terminal alveoli. There’s the suggestion of survival if only the dying monster could get a little more oxygen. Collishaw’s work might be counted as yet another contribution to the increasing number of artistic responses on the Brexit debacle.

The walls that surround Albion feature six of Collishaw’s ornithological oil paintings in a series called GASCONADES (2018). Each depicts a proud, brightly coloured bird tied by a chain to a branch in a manner similar to Carel Fabritius’ famous Goldfinch (1654). The birds, you might imagine, have left the ghost of the tree to find themselves in the city with its background imagery of graffiti, the tags of the street. Collishaw depicts beauty trapped by a surrounding ugliness. He has a Nabokovian taste for the patterning and disguises of nature, a similar fondness for layering tasty chocolate coatings over a bitter centre. Fittingly he is fond too of quoting John Updike’s precise assessment of Nabokov’s prose – “it yearns to clasp diaphanous exactitude into its hairy arms”.

The mood darkens further in the even dimmer second room with works from Collishaw’s Dark Mirror series. Three large surveillance mirrors are framed by an extravagance of black Murano glass carved with baroque curlicues. Each mirror has another LCD screen on which we see shifting forms. St. Sebastian (2017) features a Caravaggio-like image of the saint who we see gasping his last. Anyone who has seen the agonal breathing of a dying relative will recognize these with quick horror.

Like others of the YBA generation – Steven Pippin, Simon Patterson, Mark Wallinger – Collishaw is fascinated by the proto-cinematic innovations of Eadweard Muybridge. The final room here is dominated by one work, Seria Ludo (2016), a sculpture of a chandelier decorated by many small figurines. This spins rapidly and with strobe lighting a zoetrope effect is achieved. We see little carved humans and some tiny monkeys moving. They swing back and forth on branches, glug wine from bottles, vomit, piss, and generally behave badly. The title implies that serious matters be treated with a lighthearted spirit.

Collishaw has been careful to refine his interest in death and decay. As one of the original exhibitors of the Freeze show he could easily have gone for endless retreads of his attention grabbing Bullet Hole (1988) – a head wound from a pathology textbook blown up and enlarged into 15 light boxes. He has taken his fascination with the macabre and melded it with tasteful effects that ask that we look with care and not bite into everything offered.

Mat Collishaw, The Grinders Cease, is at Blain | Southern, Berlin, until 26 January 2019