Mary Heilmann and her curator Lydia Yee have a kind of Martin and Lewis / Bob and Bing thing going on.

“There’s something about your work,” Yee says earnestly “ that connects to postmodern sampling. You’re taking from all these different sources…”

Heilmann, dry as a bone: “You’re making me cry.” It’s like Who’s On First or something.

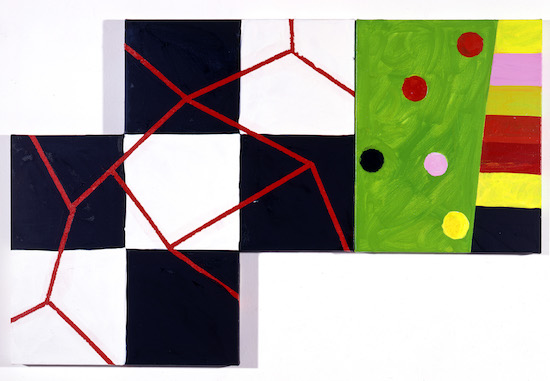

Heilman’s work seems to be always flirting with the dry, old tropes of radical modernism, only to undercut them with a personal recollection and a wicked sense of humour. 311 Castro Street turns out to be the artist’s granny’s address, its wash of pale green and blocks of abstract colour inspired by the old dear’s wainscotting and the pottery in her cupboard. An oblique composition of rectangles and right angles in black, white, and primary colours is titled Little Mondrian. It sounds rather like she’s patronising him.

But Heilmann’s grids have a fuzziness around the edges that pushes her a world away from the severity of the early twentieth century Dutch painter. The flecks of paint that intrude upon her canvases here and there don’t feel like heroic individualist gestures à la Pollock, but somehow simply there.

“A lot of the work I’ve been doing,” she confesses, “takes its imagery and its idea from hallucinations.” Maybe there’s something to that, a key to the wooziness of her grids. It’s formalism on acid.

One of the Beach Boys’ trippiest songs gives its title to a work in the upper galleries. Good Vibrations presents a pair of canvases in a sickly yellow-green, one bordered with oblongs in bright yellow, red, green, and blue. The other is spotted with rough circles in the same colours. Splodgey ceramic discs pockmark the surrounding walls as if they had just escaped from the frame of the second canvas and were gently drifting away. There is, indeed, something deeply psychedelic about this sense of colours too vivid for one medium, escaping out of the frame and into the world. But it turns out these three elements were only put together for a show at Hauser & Wirth in 2012, having each lived some separate existence for a while before that.

This kind of free translation of one medium into another is characteristic of Heilmann’s work. Many of her ceramics are basically flat, wall-based, covered in acrylic. Is it a painting or is it a sculpture? Who knows. The border between the two starts to become slippery, tenuous. A classic work from 1983 makes the gag explicit. Cup Drawing consists of seven lines of painted clay linked together to suggest a simple line drawing of a cup. At once abstract and representational, a drawing, a painting and a sculpture, conceptual yet humble and everyday, Cup Drawing can hardly fail to draw a smile.

Mary Heilmann, The Thief of Baghdad, 1983, ©Mary Heilmann Photo credit: Pat Hearn Gallery, Courtesy of the artist, 303 Gallery, New York, and Hauser & Wirth

By her own account, Heilmann’s becoming a painter began as a kind of conversational gambit. Born in San Francisco in 1940, she moved to New York in 1968 after graduating from studies in poetry, ceramics, and sculpture at the University of California at Berkeley. “I wanted to be able to engage with the artists doing minimal and primary structure work,” she says. But her attempt to catch the attention of Carl Andre or Robert Smithson at Max’s Kansas City fell flat. “It wasn’t happening.”

She chose painting, then, almost as a way of catching people’s attention, since it was so deeply unfashionable at the time. “When I would go to the bars where we would hang out, I would say I’m a painter. Then they really wouldn’t like me.” Taught for a while at Berkeley by David Hockney, “I would say Hockney was my teacher – the sculptors would hate me even more!”

“That was the style then,” she says of the combative avant-garde arts scene in late 60s New York, “to get into fights all the time.”

By the mid-70s, though, she was “really getting into painting” – albeit in a somewhat paradoxical fashion. She hymns the sculptural potential of acrylic paint, saying “You really can build it up.” At the time she lived in a building on Chatham Square, at the end of the Bowery. “We had kind of a hippie commune there,” she recalls. “Phil Glass and Steve Reich started doing their painting there. It was a big scene – and it was rough.” Living on the edge of the lower east side, she became inspired by the vivid colours of the signs of Chinatown.

As we walk through the three galleries of her paintings and pottery at the Whitechapel Gallery, Heilmann beams proudly in a polka dot skirt with matching scarf. It’s an impressive body of work, at once deeply embedded in the movements of her times and somehow sui generis, highly individual and at times deeply personal. One canvas in the upper gallery, bearing the faint image of a chair in white offers a moving memorial to a lost friend. “Ghost Chair represents somebody not being there anymore,” she says. “This remembers Robert Mapplethorpe. It was made just after he died.”

Her latest works have a deeply immersive feel to them, with vivid imagery drawn from the Hawaii waves and the Californian highways remembered from her childhood. “They’re supposed to make you feel like you’re on the highway or in the water,” she says. One of these recent works, The Green Room takes its inspiration specifically from an anecdote by the American journalist William Finnegan. His book Crossing the Line records the year he spent in apartheid South Africa, teaching in a school for “coloured” children and pursuing his lifelong passion for surfing. One particularly vivid passage cited by Heilmann recounts his experiences surfing on LSD.

“But how does geometry relate to the ocean?” asks Lydia Yee, gesturing towards the right angles and blocks of colour on the canvas.

“Well,” shrugs Heilmann, “maybe if you take some acid and jump in a wave, you’ll think it’s a box.”

Mary Heilmann, Looking at Pictures, is at the Whitechapel Gallery until 21 August