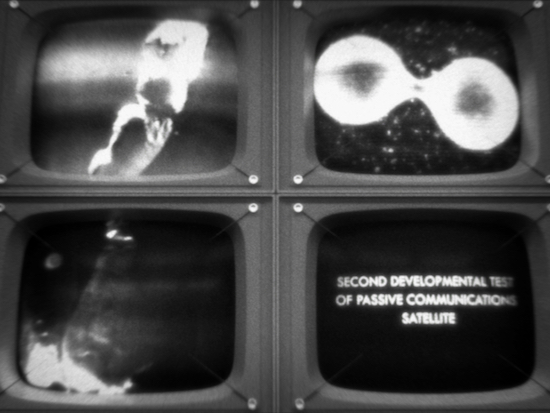

All images: Mark Leckey, Dream English Kid, 1964 – 1999 AD, 2015, 4:3 film, 5.1 surround sound, 23 minutes. A Mark Leckey film in association with Film London Artists’ Moving Image Network and Arts Council England

There’s a funny kind of excited recognition that takes place when you meet a person from your hometown down here in the capital. As I’m serving up the usual dose of introductory small talk, he senses something in my voice and sparks up, “Where are you from!?” Caught off guard his tone shifts slightly – higher, faster. “Are you really! Where about?” near Penny Lane, I reply. “A proper scouser then. I’m plastic, a bad wool,” referring to his upbringing on the periphery of the city. This shared language makes me feel at ease, I drop the small talk. He takes a moment to adjust himself, surveying the hallucinogenic capsule in the ICA’s lower bar that I’ve bagged to sit in, the walls melting yellow, orange, blue. “It’s like an Amsterdam drug den from the 80s,” he jokes in his soft northern lilt.

In 1989, a young Mark Leckey was first invited to the ICA with a work titled Hard, as part of the New Contemporaries: twin wooden boxes containing back-lit photos of strip lights, reminiscent of eerie late night motorway escapes. More than thirty years later, with a Turner Prize and Tate Britain retrospective under his belt, he’s back here talking to me about the echoes of a youth that still haunt him, ghosts and their dwellings – under the bridges of those dimly lit motorways that once promised something more.

In 1999, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore thrust Leckey into the spotlight, lending him a reputation as contemporary art’s Wunderkind. The film charts the evolution of musical subcultures from Northern Soul to Rave, celebrating the rich vernacular of working-class street culture. Fast-forward to 2020, Fiorucci still possesses an enduring mercurial appeal for new generations. Although contemporary digital culture provokes a different set of anxieties, its desires remain matched by each shuddering twirl of Fiorucci’s phantoms. The longing for transformation that will propel us beyond impasse, the dance that sets in motion the change of the seas.

As he sits across from me, pushing back his long brown hair, his eyes start to wander. It’s clear that Leckey’s world is still partly elsewhere – some in-between place where the past and the present collide. The grey flecks of his beard reveal his age, but his pirate-like demeanor, that single pearl-drop earring, summons the rebellious lost-boy he once was, and perhaps, on some level, still is.

Your retrospective exhibition O’Magic Power of Bleakness has just closed at Tate Britain. Two older works, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999) and Dream English Kid (2015) sit under a full scale replica of an underpass off the M53, setting the scene for your newer piece Under Under In (2019), in which a group of tracksuit-clad boys play out an old folk tale about a ‘changeling’. What was your thinking in bringing these things together, scallies and fairies?

I was looking for something conflicted. I’ve been a scally, and I’ve seen a fairy, so I was trying to incorporate these two things that seem irresolvable, trying to resolve them. I went from being ten years old and believing in magic to very quickly, within two or three years, living for something quite violent and aggressive. More than anything it was a way of talking about class. Talking about scallies, people think ‘oh its nostalgic’, but the fairy gave me a way to talk about this other stuff that we present as magic, really it’s more about a kind of realism.

There’s a really interesting relationship between class and the supernatural.

I think it’s something to do with not being listened to. You’re not seen as a fully rational agent. You can’t speak properly, you don’t know how to articulate yourself, you don’t know how to cause a fuss correctly, all those things that the middle class carry naturally.

I had to adjust a lot when I came down to London, and to the art world. I had to make these massive adjustments to myself and re-learn all that stuff. When we talk about magic, it’s folklore, isn’t it? That’s got its own kind of language, and it’s not taken seriously in the same way that most working class culture isn’t taken seriously. It’s starting to, but still in the art world it’s like, ‘oh is that like Ken Loach?’ No, it’s not like fucking Ken Loach! It’s a bit more complex than that. Magic gave me a way to broaden it in some way, make it not appear so constrained.

You trace this ancient link to magic up to the present most interestingly in the dialogue of Under Under In, which mixes northern slang with a strange Old English tongue. Can you talk about your use of language?

Yeah, when the main character changes, he starts speaking this kind of weird Old English tongue. It’s not actually Old English but more like Old Scots. They used to write these amazing things, almost like rap battles. They’d slag each other off in rhyme and get really brutal, I got a lot of it from there. ‘Your mimicking!’ is my favorite one, ‘You’re fucking mimicking!’ All this stuff about being full of worms, it’s great, this elaborate old language.

At one point a kid says ‘he’s away with the fairies him, laa’. It reminded me of something your nan would say when you start getting ideas above your station, when someone dares to question the way things are. What was your writing process like? How did you come to these expressions?

My process for everything is essentially sampling, nothing comes out of my head. It’s all things I’ve found. It’s all stolen. I started reading lots of stuff about folklore, fairies, cutting and pasting, building it up until I’ve got something. Then I had a lot of these classic youth films – Quadrophonia, Kids, Kidulthood, those kinds of films, which are all basically the same. They focus on one kid who wants something better out of life, and he’s getting dragged back by his background. It’s always that same arc. I took loads of lines from this stuff. It’s always, ‘Oh I wanna get outta here!’ ‘Get outta where?’ ‘outta here!’. I wanted it to be very clichéd, to smash into this fairy stuff and not really work together, but have one superimposed upon the other.

It’s the first time I’d ever heard those voices in a gallery and I found it quite jarring – I kept looking at other people to see if they understood. How important was it for you to preserve these accents?

It was about something that happened to me when I was young, so I wanted the accents to be regional and specific to where it happened. Where I grew up it was a mix: Scousers, Mancs, Welsh, it wouldn’t have made sense to work it with any other accent. I like the idea of having the M53 coming all the way down through the Tate, and them being carried down with it. The wrongness of it, that you picked up on. It’s like, ‘Why are they here?’ It’s kind of incredible to think you still don’t hear those kinds of accents here. In the Tate there was all this talk of subtitles. An accent carries all this history and weight. I liked the idea of these voices rebounding, echoing around the institution. The story is a half-hearted allegory of how I ended up here, that I got chosen by fairies, plucked out from under the bridge and brought to the magic marbled halls of Tate Britain.

There’s something very uncanny in that idea of the changeling. Being taken away and returning somehow different…

Which I feel when I used to go back home, you’d feel this process of mutating. There’s a suspicion about you, with all the new airs and graces you’ve adopted, your cleverness and the rest of it. That seems more pronounced to me over the last few years. In some ways Brexit seems about those who’ve experienced university and those who haven’t. That kind of bifurcation.

I was the first one in my family to go to university. It was a moment where quite a few people from my background went to art school, then that seemed to dip away. Now, even though fees increased dramatically, the amount of young people in education means more people have that experience, so whether you have an education or not becomes a more pronounced kind of cultural difference.

All those things were percolating around when I was making the show. So it’s not just about class, it’s also about education – or a university education. Becoming book smart. However you want to put it, you become acculturated into this other kind of language.

There’s a sense of doubling, or splitting.

It feels like that doesn’t it? It’s always been a fault line in British culture; I think it’s just become more pronounced.

Do you ever wonder what would have happened if you hadn’t left the North?

I was thinking about it the other day, actually. The reason I keep going back to that bridge, and to youth, is cause to talk about youth is another way of talking about class. That’s why it’s never about nostalgia for me.

When I left school in the early 80s, there was no work and I just ended up getting in trouble and being lost. There was a sense of hopelessness. Liverpool and the surrounding areas was a wasteland. There was nothing. I left school at this moment where you’re standing on the threshold of your life looking out and there was just nothing. I think that marked me.

I always have that anxiety: there’s never hope that something will come along. I think it was like that for a lot of people back then. It was pretty bad. That whole idea of ‘managed decline’. I thought I was gonna go and work at Cammell Laird and then it just closed down, so that was that.

Apart from that there were YTS schemes, you’d get an extra fiver when you’d go to sign on, but they kind of forced you. You’d supposedly learn a trade but they just put us in a warehouse where we’d build a brick wall every day then knock it down. Totally pointless.

There was that, or you’re on your way to borstal or something. This is what I mean about talking about all this stuff, you end up in all these clichés. Let’s go back to magic…

You have these lads that look like sporty druids in Adidas capes and trackies. Can you talk about that investment in reclaiming these brands?

It’s funny. I follow a lot of young working-class artists on Instagram and they keep making stuff about trainers, Nike Air or whatever, cause it’s such a totem of class. That’s what Fiorucci Made me Hardcore means. it was the label everyone wanted when I was a young scally. I’ve always liked that idea of over investing in something like a brand, which is essentially out to exploit you but you invest in it so much that you make it magical, like a sigil, or a rune. It becomes a spell: Nike, Adidas. A magic word.

I’ve got a little girl who’s seven, and she lives in a world that’s all potentially magic. Within her imagination, the possibility of supernatural things sits alongside school and real things. There’s no distinction. At the same time she’s kind of assaulted by magic. What she watches on TV, the magic there is some kind of code for consumerism at its most insidious. They deliberately confuse children’s appetites by mixing magic and stuff up. I sit with her and watch all of this, some of it I really like but some of it is evil. It’s how you approach magic.

There’s that classic line by [Arthur C. Clarke] who says, ‘any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic’. And Marx talks about how the commodity has these almost magical properties. We’re in awe of them because they appear to us as supernatural. It’s like this black box idea: you can’t access the thing, it’s just this mysterious slab. Kids are fascinated by them not just because you’re using them but because they look like amulets or something. They look magical.

Fiorucci documents British counter-culture, which seemed to thrive in forgotten spaces. Rave, for example, was able to access these gaps where culture could mutate into something weird and unexpected. Where do you think those gaps exist now? Are they digital?

I think it has to be, doesn’t it? Geographically, physically, they’ve been plucked up. I can think of two reasons for that. One is, when I first came down to London in the 80s, you could still see how damaged London was by the war. There were literal gaps in the fabric of the city – all these broken places that you could get access to.

From the 80s, this hyper-capitalism moved in and the people who were filling in those gaps with subcultural capital were replaced by real capital. You can make the argument that ravers were just estate agents of a different ilk: they were really good at sniffing out properties. Artists too.

Everything feels costed now, but that idea that the digital is free, that’s not true either. It’s hard not to sound totally hopeless but part of the dynamic of any subculture is that they’re being squeezed. The reason this culture erupts is because it’s been pushed out of somewhere else.

In terms of music, it’s still happening. You can hear it, it’s like ‘yeah, you’re being squeezed cause you’re making all this weird shit over there…’ Some people complain that it’s all been leveled out, blanded out, but it doesn’t feel that way to me. And university culture, that feels very big and alive, like there’s a power to it. It’s angry and that feels like something. This student disquiet, it never happened in my time. It feels like something that’s closer to the 60s.

Yeah, we’ve been out supporting the UCU strike this week…

Exactly. We never did that. It feels like something very new is being formed, a new kind of politics and engagement with the world. Even in the art world, the art I was taught feels dead. It has continued, but in this zombie way. Something else is happening in its place, an idea that’s very different, more to do with care.

I found ‘A Supernatural Riot’, the final act of Under Under In, very optimistic. It seems to be making way for something new. Is that a reflection of this feeling that something is bubbling under the surface?

I think that’s just what happens. In America, the UK, other places in the west where there’s a history of pop culture and an alliance with politics, I’m always hopeful that something will rise up from that. You get places where the oppression is so great that it doesn’t produce its counter-culture. There has to be a historical precedent, I think, in order for that to happen. When people are being pushed out of something, there will always be a push back, and it produces culture.

Under Under In is about a working class culture, which isn’t this culture – it invents itself, there’s a mind there. They respond to this thing by mimicking the bridge – a weird, passive ‘well, we’ll be the bridge then’. It was based on these mass fainting fits. I like the idea that you’re getting more and more constricted and the only response you have is to faint. In that absolute negation, that passive act, the authority is completely lost; they don’t know how to react to it. I think that’s beautiful.

It’s the same with the idea of a riot as mindless. It’s not. People are within that thinking about how to make it continue, how to make it effective. It’s a thinking response to a situation, and out of that comes creativity. It’s like Hong Kong, where they’re fighting with umbrellas, making their own catapults.

Finally, what advice would you give to young working-class artists today given everything we’ve discussed?

Call on your own sensibility, the culture you come from; the art one isn’t more intelligent than that. Don’t let it overshadow or intimidate you. I think it’s really necessary to find a language to make art that’s not academic. We need more people to do that, without just being unthinkingly pop. I’m much more comfortable with music and part of the reason for that is there you can get to see working-class creativity on a phenomenal scale. I’m still waiting for the day where that filters across. I guess that’s it: find your own vernacular, cause it’s there. When I went to art school my dissertation was a disaster and I thought I just wasn’t clever enough.

What did you write about?

The Situationists, but it was very bad. I got a 2:2, so I thought, ‘that’s not for me, I don’t have those capabilities’. Then I started making videos about things I felt at home with, and I didn’t care what they meant outside of that. It was enough that they meant something to me and I was able to work with them without any anxiety about whether I was doing the ‘right’ thing. It was like, this is mine, and I understand this complicity so I can do what I want with it.

You have to find that, I think. If I start to think too much about what it is I’m doing, I get the voice of a Frieze review in my head going ‘Leckey is blurring the boundaries between…’, and I have to shut it up, cause that’s the one that’ll destroy you.