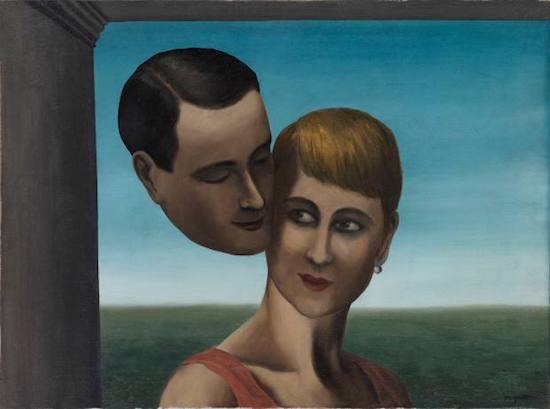

Les amants, 1928, Oil on canvas Photo: Damien Griffiths, Courtesy of Galerie Haas AG, Zürich. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

The new exhibition at Luxembourg and Dayan presents René Magritte (or: The Rule of Metaphor) Paintings from the Years 1927-30. The exhibition is modelled on the non linear hang of Magritte’s exhibition, Word vs. Image, hosted by Sidney Janis Gallery in New York in 1954. From this exhibition his work began to attract attention among a new generation of artists, including Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol.

The celebrated Belgian Surrealist artist, René Magritte (1898 – 1967) was immersed in the revolutionary movements of Dadaism, Metaphysical Art and Surrealism, which emerged from political uncertainty and upheaval between the two world wars and challenged the definition of art by rejecting the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society – instead expressing nonsense and irrationality in anti-bourgeois protest. In the late 1930s Magritte gained the support of the aristocrat, poet and greatest English patron of art of the early 20th Century Edward James (1907 – 1984). James also sponsored Max Ernst and Salvador Dali – who reportedly described him as “crazier that all the Surrealists together” – as well as a host of more minor artists.

René Magritte (or: The Rule of Metaphor) Paintings from the Years 1927-30 focuses on these pivotal years in his artistic maturation. After a solo exhibition in his Brussels gallery in 1927 was branded a failure by critics, Magritte moved to Paris for three years where he entered the world of the Surrealists. The Manifeste du Surrealisme by the French writer and poet Andre Breton (1896 – 1966) defines Surrealism as “Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one purposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.”

Surrealism had begun as a largely literary movement – its founders were sceptical about the value of painting. Magritte, too, with his background working with his brother in advertising, had always had an interest and admiration for poetry and the power of words. “He was well versed in the history of philosophy” writes Cath Pound in a recent BBC Culture post, ”he was aware that from Plato to Hegel, figurative representation had been dismissed as a confusion of the senses and poetry considered the highest form of human expression. Magritte believed that an image was capable of expressing thought as poetry, and rather than calling himself a painter, he preferred to describe himself as a thinker who communicated through paint.”

These years in Paris are significant for the evolution of his word pictures, coined ‘collage paintings’ by Max Ernst. The works presented in this intimate exhibition reveal his philosophical enquiry into the relationship between literal and figurative language, where words are made of the same material substance as images, i.e. paint. The inclusion of painted text and painted image enables a unification these two otherwise different linguistic realms. Alma Luxembourg tells me “this period for Magritte was crazy edgy, and the birth of the core of his thinking.”

The title of this exhibition, The Rule of Metaphor, suggests that Magritte was dissatisfied with conventional metaphorical associations. He believed “an object is not so wedded to its name that one cannot find another name which suits it better.” In this body of work, Magritte juxtaposed images with text, with misleading connections to bring awareness to the difference between representation and actuality.

The smallest, most unassuming piece in the exhibition L’usage de la parole (The use of speech), made with India ink on paper, captures the crux of this principal idea. Shapes are assigned a word, but the pairings don’t all make sense. One shape labelled ‘gun’ and another labelled ‘cloud’ are acceptable to one’s idea of what a gun and a cloud (could) look like, but the word ‘horizon’ is contained within a single round form.

La clef des songes (The key of dreams) depicts objects with words that do not accurately describe them. Magritte labels a bag as the sky, a pocket knife as a bird, and a leaf as a table. Only the sponge-like object could resemble ‘l’eponge’ (a sponge), albeit a very strange one. In his three years spent in Paris, Magritte produced more than forty paintings and collages that are now referred to as the word pictures cycle.

La clef des songes, 1927, Oil on canvas, Bpk / Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

During this still impressionable period as an artist, Magritte was inspired by the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico (1888 – 1973), who was developing the Italian Metaphysical Art movement with Carlo Cerra. Echoing the Surrealist ideology, Chirico believed that “to become truly immortal a work of art must escape all human limits: logic and common sense only interfere. But once these barriers are broken it will enter the regions of childhood vision and dream.”

Magritte’s transportive collage paintings operate in the same realms as poetry, leaving impressions on the mind to arouse the imagination. Once logic is eliminated, painting has the power and the freedom of endless possibilities. The artist can name something something it’s not, make a boulder float in the sky (Le Chateau des Pyrenees (The castle of Pyrenees)); a steam train drive through a fireplace (La Duree poignardee (Time Transfixed)) or decapitate a body – as seen in this exhibition in Le genre nocturne (The nocturnal genre) where a woman is missing her head, and in Les amants (The lovers) where one of the lovers is missing a body. It is real in the imagination and in the undeniable existence of the painting.

The exhibition demonstrates Magritte’s exploration of abstraction as he moved towards more non-sensical forms and unresolved situations. Le parfum de l’abîme (The scent of the abyss) and La prevue mystérieuse (The mysterious proof) are the epitome of this journey. The forms do not remotely resemble the words assigned to them, and in Le parfum de l’abîme, even the shadow does not seem to belong to the object.

We look for signs to find the resolution in the work. Belgian poet, Paul Nougé (1895 – 1967), suggested Magritte’s titles were “a commodity for discussion, rather than explanations.” As with interpreting poetry, the experience of the piece is the viewers own. In the gallery, collectively, the works create an uncanny, dreamlike environment for the mind to wander in. They can be unsettling and curious, yet at the same time visually nourishing and playfully challenging. The exhibition is a fascinating insight into the development of such an iconic painter. Magritte’s word play creates a space for thought to venture outside the normal remit of what is possible. And anything is possible through painting.

Magritte (or, the Rule of Metaphor) is at Luxembourg & Dayan until 12 May