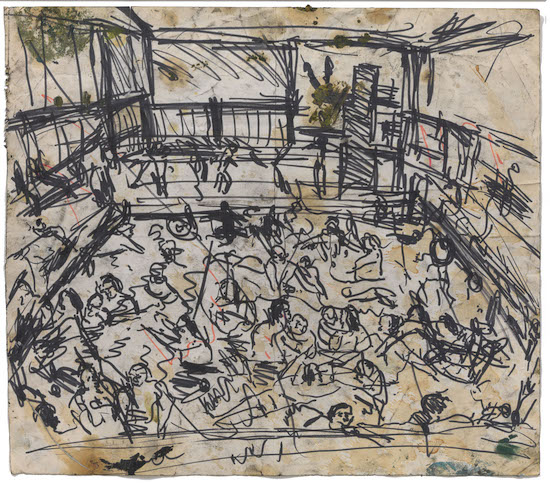

Leon Kossoff, Children’s Swimming Pool, 1969

If we had been in London in the spring of 1962 I would have suggested we arm ourselves with a well-researched address book and take a long walk.

We could have dropped in on Francis Bacon, by then a celebrity, preparing for his retrospective at the Tate Gallery in a tiny flat in Kensington, paint seeping into the forearm he used as a palette.

We could have watched Lucian Freud, temporarily forgotten after a first moment in the sun a decade earlier, “working underground”, as he put it, in the dark slums of Paddington.

We could have spent an hour ogling at the unflinching optics of Bridget Riley, a bright new talent fresh out of a stultifying job in advertising, at her first show in Mayfair.

We could have visited the Royal College of Art to see a gaggle of dreamers – including David Hockney, Allen Jones and Frank Bowling – confounding the austere tastes of their teachers with hope and bright colours.

A serendipitous clash marks an unforgettable burst of artistic energy in British history: of an exhibition of the “London painters” at Ordovas gallery on Savile Row and an oral history of the same “Modernists and Mavericks” by critic Martin Gayford. “London after the war became much more important than anyone would have thought in the 20s or 30s,” Gayford explains. “I’m making the case that in the 50s and 60s it was an important place in world art.”

Ordovas holds a small sample of the evidence. In an un-shown, unfinished late self-portrait, Freud’s old face emerges from the canvas angular and haunting. A number of pictures, including a Leon Kossoff self-portrait in which the artist’s eyes seem to bleed paint, exemplify the observational talents of Kossof and his contemporary Frank Auerbach. And for the first time, Freud and Bacon’s arresting portraits of Bacon’s doomed lover, George Dyer, are shown side by side – Freud’s the straight portrait of an acquaintance, Bacon’s a twisted triptych of a soulmate, really part portrait, part self-portrait.

Viewed with the history from which they had come, these works are dizzying. London during the war was the scene of great art: Henry Moore with paint and Bill Brandt with a camera made the bomb shelters of the Underground look like a desperate necropolis; above ground, iconic visiting American Lee Miller pointed her lens at the shadows of the rubble.

But the city remained a cultural wasteland. Freud, the Jewish grandson of Sigmund who had escaped Nazi Berlin in 1933, suggested that in London in the early 1940s there were no more than six professional artists plying their trade.

Thankfully, things changed. The war ended and a new prime minister in Clement Attlee expanded scholarships for students, helped ex-servicemen go to university and invested heavily in the arts.

Suddenly a generation of Londoners, many of them immigrants from the British countryside and abroad, considered art a possible career. Some, like Kossoff, had themselves served on the battlefield. They took on cheap rents in what now seem like fairytale addresses – in Paddington, Freud was in the heart of what is now called Little Venice. So many flocked to the Camberwell School of Art in the spring of 1945 that extra bus services had to be arranged.

But it was not just social and political change that transformed London into a world centre of painting. It was also the raw talent of its painters – none more than Bacon, who had arrived, a Dubliner by birth, in the late 1920s. “I think perhaps one of the reasons for London’s rise was the completely unpredictable advent of the extraordinary and unique personality of Francis Bacon,” declares Gayford.

There is no doubt about Bacon’s continuing attraction. On the morning I visit Ordovas, a man in tweed enters, passes up an exhibition pass and, without as much as a glance at another painting, makes a beeline for Bacon’s Fury (c.1944), a nightmarish monster-portrait painted around the same time as his career-making Three Studies for Figures at the Base of A Crucifixion, and stares at it, body cocked like a perturbed spaniel’s, for no less than ten minutes.

Bacon was the magnet who kept many small cliques of artists of disparate age, origin, training, and stylistic impulse in the same universe. “His impact transformed a lot of other people’s lives and expectations,” says Gayford. Not only did he have his inner circle with whom he drank in the depraved Colony Room Club in Soho: Freud, whom he reportedly saw every day for twenty-five years after meeting in the mid-1940s, but also Auerbach, Michael Andrews and others (rarely, if ever, Kossoff). He also took an interest in younger painters like Hockney and Bowling. “It was a small world,” says Gayford.

They were underdogs. Across the Atlantic, abstract expressionists were wowing the globe with their awesome canvasses. In Europe, an unstoppable march towards abstraction was underway.

Bacon spearheaded a peculiarly British reaction. “Just by force of talent and personality, Freud, Bacon, Hockney and the others changed the narrative of art history,” says Gayford. “That took quite a bit of courage, as well as cheekiness.”

Freud, charmed by the idea of the “naked truth”, stuck unwaveringly to his human forms. Bacon painted bodiless inner torment but did so through figures, many based on photographs. Auerbarch and Kossoff dared to paint London. (“London, like the paint I use, seems to be in my bloodstream,” Kossoff once said.) Hockney travelled backwards through the presumed narrative: starting in abstraction before adding words, figures, objects and landscapes and settling into a defiant figurative stupor.

This is not to say that Gayford has written a history of a salon. “There’s no movement,” he points out. “There’s no manifesto. There was no group discussion, certainly not a publication in a way that you got with the Futurists, or even the sort of loose grouping you got with the abstract expressionists.”

Neither is it to say that this was a simple kickback of figuration on abstraction. Both Riley most famously, but also Gillian Ayres, a “tremendous, ebullient personality” and a “really marvellous and underappreciated” artist, who sadly died two weeks ago, were abstract through and through. It is noticeable that it was these women, whose lonely predicament is so well captured by a photograph of Ayres and her male classmates in a pub at Camberwell in 1948, who stood up for British abstract art.

1948 photo by Gillian Ayres, the Walmer Castle pub nearby to Camberwell School of Art.

Courtesy Gillian Ayres

But whether abstract or figurative, Gayford’s book shows that the London painters, if not a strict “School of London” as American adopted Londoner R. B. Kitaj later proposed, shared a common spirit. They were irreverent, unfashionable, plucky, sceptical of conventional wisdom. Riley’s stiff compositions were a rebellion against Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. Ayres rebelled by peppering her abstractions with recognisable plant forms.

As the years went by many of them went their separate ways. Hockney became a Californian. Ayres moved to Winchester and then Wales. Bacon died. Freud grew old in London. But they left London permanently marked and the assumed history of modern art thoroughly refused. For that, we owe them a great debt.

And what of London? What creative forces might one discover on a spring stroll there today? Are new Hockneys and Ayres changing the world? On the one hand, the question seems disingenuous. Glance through social media and you will see London remains a trove of new culture.

And yet it is hard not to feel that something has been lost along the way. The last obvious “new generation” arrived in the 1990s: the Tracey Emins and Damien Hirsts of this world, as well the Gary Humes, Peter Doigs and Jenny Savilles in painting. “The young British artists aren’t so young now,” admits Gayford.

Many of the 1990s generation have migrated away from London. Rents are no longer cheap enough for struggling artists. If bohemia can still be found in the capital, Gayford suggests, it is not in Soho but way out in the “far east”, or south London. Hockney apparently thinks it has disappeared – though others say he simply no longer knows how to find it.

“Maybe Facebook’s ruined everything and Mark Zuckerberg’s to blame,” suggests Gayford. “But I’m told that there are equivalents to Soho and the Colony Room. Younger and poorer people are still living in bohemia.”

Whatever the case, it seems unlikely that a group of young talents is about to reinvent British art in their own image. Perhaps we should just be thankful it happened once.

Martin Gayford’s Modernists and Mavericks: Bacon, Freud, Hockney and the London Painters is published by Thames & Hudson on the 26th April. London Painters is at Ordovas until 28th April