Liam Gillick, A Depicted Horse is not a Critique of a Horse, Kerlin Gallery

Liam Gillick rose to prominence in the 1990s, producing installations inspired by corporate aesthetics and situations. A progenitor of relational aesthetics, his work is not characterised by media but more a sense of duplicity, providing space for discussion and disagreement in place of clear answers.

Living and working for the past two decades in New York, Gillick’s work appears to take influence from a perspective on the front lines of contemporary art’s metamorphosis, with references to hierarchical structures, institutional power and the facades presented therein.

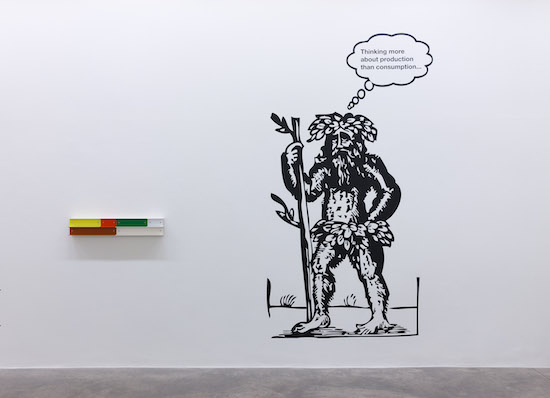

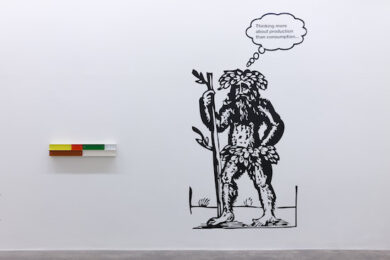

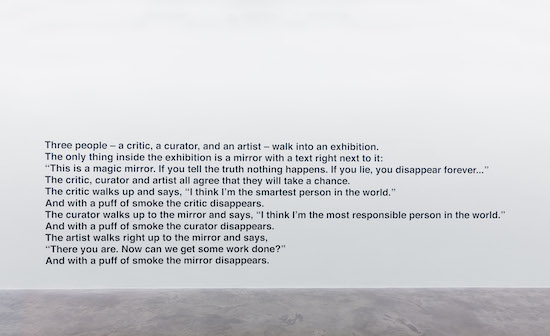

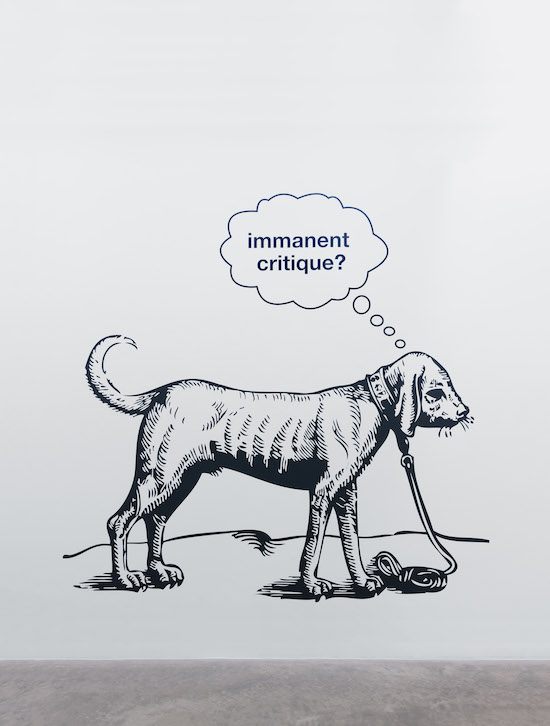

The exhibition around which this interview is focused (A Depicted Horse Is Not a Critique Of A Horse November 23rd through January 19th at Kerlin Gallery in Dublin) is centred around the ideas of production and dissemination. Utilising authorless woodcuts presented as wall graphics, abstract sculpture and text, Gillick asks questions about the nature of not only being an artist but the nature of being a worker and the nature of production, consumption and representation as a mode of existence.

Is this your first time seeing the show installed?

LG: It was half done when I arrived. I tend to plan very precisely, I was an early adopter of computing as a way to make plans and think about spaces. We changed some things on that first day but generally I trust the ideas that you have when you’re in private, it’s the middle of the night and you’re staring at screens and drawings. Reality is a bit more difficult to me. The old adage of an artist standing and stroking their chin doesn’t really appeal to me – I don’t trust myself.

That action kind of relates to the wall text in the show, when you’re on you’re own with your ideas, you haven’t got this outside force affecting you.

LG: Yes, I don’t know what it is but I feel like my shows here and in Dublin in general often have this element of a reflection on what it means to be an artist. Not a very clear reflection, kind of a fuzzy one. I think that’s because I find it such a literary city. It seems to be a good place to step out a little bit and think about the problem of being an artist, the hubris and delusion of being an artist. It could be my repressed catholic roots coming out. The awareness of my own uselessness.

Liam Gillick, What is a mirror for?, 2018, matte black vinyl on wall, 300 x 740 cm

I know what you mean about Dublin being a literary city. I think it’s because people talk to you there. It’s not like London or Berlin where people will actively avoid addressing you. There seems to be more conversation happening there in general.

LG: I agree, growing up in Britain in the 70s, people always assumed I would be like that too. There’s an assumption about writing, communication, speaking… It’s half true in a way. It feels right. On the other hand these are also constructed ideas about identity. I don’t have an authentic relationship with any of that, but I do in a way because it was assumed. It goes with the name.

My main work has happened in continental Europe. I’m interested in working within contexts where the idea of being an artist is under stress in a different way than in Britain. I did come up in that 1980s British art world where things were starting to change, a lot of that based on class. People from different social classes were going to art school and decided to be artists instead of musicians. The institutional context or critical context in Britain was still weak. It didn’t threaten or mark or make things difficult. I think there’s a skepticism or complexity of how you deal with things like parody, storytelling, satire – the history of questioning hierarchies, that I find more productive in Dublin.

Britain is an odd culture. There’s always this worry about whether or not people will get it. The figure of the artist in Britain is a very complicated one. I think it’s still an almost continental idea, which of course means dangerous or not real or a con or a trick. I find this really fascinating. As a pretentious teenager, I couldn’t wait to get out of London and into an environment where the blurred lines between disciplines were seen as an advantage and not a problem.

I think that’s still a valid criticism of art in the UK, particularly London. Everything feels very safe at the moment, like everything is trying to eke out it’s own space within a critical context or market context that may not even necessarily be there – it’s almost about being brought in.

LG: Yes, but I have to say that having grown up and gone to art school in London, there are a lot of things about it that are very unique. The first statement is often skeptical or negative but there’s another layer there. The history of London as a place is as two cities divided by class, in a sense. People don’t always tell you what they mean, which is an interesting environment. Historically in the last twenty or thirty years, Britain has been a very interesting place for art. People have wanted to go there from all over the world but you wouldn’t know that from asking anyone.

Consumption Channelled, 2018, powder-coated aluminium, 32 x 45 x 8 cm

I always wonder about this idea that people have to understand art. I think that’s the primary problem – this feeling that everything would be great if everyone was better educated and got it. I don’t mind a bit of not getting it or not liking it. I got in involved in art by being interested in music, everything around Factory Records and that whole thing was interesting to me. I went to art school because I didn’t want consensus or agreement. I wanted things that didn’t work. I wanted things that were about withdrawal or not communicating clearly. That’s why London can be an interesting place to be. It’s quite tribal. It bemused me a lot when I’d first go to places like Cologne in the early 90s and there’d be punk, embryonic hip hop, and then Pink Floyd on the same radio station. Where I came from, you had a tribe or an alignment. I still find that interesting. Contemporary art has become a space for people who wouldn’t just categorise themselves as artists. Cultural workers who want to create a space in which to do something.

That’s kind of where my own interest in art stemmed from – it seemed to be a space where the tribal element was gone. It seemed to be about thinking or doing or the conversations around things. I always saw it as being a space where you could go to spar your ideas, to do some intellectual running around and to see what people think about your ideas from their context.

LG: These are to do with the difference in mediation and hierarchy – who is protecting you. It’s very hard to explain to people in the beginning what a gallery is. It seems like this sort of mystery set up. Is it just a shop for rich people? How does it relate to the artist? It’s subtly different to the relationship between a band and manager. The manager is up against it, trying to create possibles and space around the music so that they can be free to do what they want. A gallery half does that, on the other hand what it does is function as a kind of gatekeeper. It’s subtly different but it’s different enough to create the thing that you’re talking about. The artist and gallery kind of stand side by side and look out into the world.

I originally thought of galleries as being a space. Where you put your art. That’s it. Then I saw it as a sort of badge, like what league you play in. “Are you Premiership or League 2?” Then I thought about it as a protector, like deciding how the artist is viewed. It’s not really the same as a manager but it’s definitely different from something like a label. I see galleries a lot of the time as context generators. You might walk into a gallery and see something and think, “Well, this isn’t really working for me but by virtue of it being here, it must be doing something”. It can give work a sense of weight just by virtue of being there. It almost protects the artist from criticism.

LG: It’s contradictory, it’s many bad things and good things at the same time. Yes, essentially it is a shop for rich people. I remember going into London as a teenager and seeing all these sort of empty shops and not knowing what they were, but knowing for sure that they weren’t for me. It’s a kind of perverse form of advanced exchange that happens right next door to a sandwich shop.

It sort of creates an invisibility cloak for an artist – they’re showing you off and hiding you at the same time. That’s why it still works. It’s a unique space. If you look at it from a social perspective, it’s intolerable but if you look closely, it’s doing something else on the quiet. Like how now in London there’s a whole new community who don’t care about galleries. They work around public spaces, improvised spaces or discourse. But that has it’s own set of psychological, economic, and physical issues. That’s what interests me, these kinds of structures.

Liam Gillick, Critical Tiles…, 2018, matte black vinyl on wall, 300 x 300 cm

It’s almost like an illusionary power structure. One of the things I like about galleries is that they’re a name and an actual place that you can go. A gallery that I wrote about for tQ a while back called DOOMED was a really interesting example of this sort of anti-art art gallery. They sort of recognised the need for a space and a hub for the community but did it from a standpoint very actively outside of the art world. They had some amazing shows and kept it going for years. Spaces like that are so important.

LG: Well that’s one of the reasons that I moved to New York in the first place, certainly why I stayed. I’ve been on the board of Artists Space for years now, which is one of the great independent downtown non-profit spaces. From the outside, it’s still very much from that SoHo 1970s legacy of people experimenting in a big abandoned space. If you look at what they did, their melding of disciplines was more possible in New York to bring in more people.

It’s because of geography. New York at that point was a place where certain people gravitated to who were not all artists but all were creating. They found themselves together in a kind of constellation. Some of that still exists in New York. It is still possible to go to something and encounter someone who doesn’t consider themselves an artist but does want to operate in this empty one. It’s a very interesting one of trying to decode what’s going on.

I’ve always thought of New York as being really good at fucking with things. That sense of the visibility of semiotics of exchange is really interesting. That might be the most pretentious thing I’ve said to date but I do mean it.

As more and more sites of retail disappear, just like in Britain, it is really weird walking around parts of downtown manhattan. You’re mostly encountering things that are stand ins for something else, even if there’s a shop that does sell things, most of their business is done online.

That’s interesting because theoretically it should mean that the cost of space goes down as it becomes less necessary for commerce to take place. You don’t need it to make money, so why can’t we take over those spaces again? They became available in the first place due to an economic downturn, so they should become available again as they become a drain on profit to these businesses functioning online.

However, it’s like you said, having a physical site has a semiotic language. They’ve come to symbolise the idea that you are established, or successful or important because you can afford to just maintain this building for no reason other than to have a physical imprint on an environment.

It’s difficult because if you essentially require a room to show art in and a place for people you think are interesting to come and hang out on the first Thursday of the month, this kind of peacocking is really counterproductive.

LG:[Laughs] Yes, I know. That sense of unresolvable contradiction actually ties in with the show here at the Kerlin. It happens between the abstract forms. They look sort of sexy but are at a strange scale, a domestic scale. Combined with the graphics that are all somewhat about production, at some level. It creates this contradiction between the desire (that I know is idiotic) for a universal abstraction, maybe yoga is the only abstraction left today?

Hot yoga.

LG: That’s kind of a horrific thought. Combining this with the self-conscious visual statements clearly undermine the possibility of that happening. I’ve been really interested in this book recently that is going back to an exhibition that [Jean-François] Lyotard did in Paris in the early 1980s called Les Immatériaux. He tried to do an exhibition about the difference in the relationships between people and objects.

It’s been really fascinating reading that because we’re in a situation where the relationships have changed again. Maybe I’m not in the best position to tell what that is, maybe I’m too old or too stuck in my world but there is something definitely going on. A new shift which is not the same. As they say in the book, looking back on the 1980s, it’s not any longer about pure communication or a kind of ecstasy of exchange, there’s something a lot more neurotic and anxiety producing going on. Maybe you can tell me?

I feel like this anxiety driven, sci-fi styled, overly didactic artwork is being produced en masse at the moment, especially in the UK. It’s completely homogenised. It’s everywhere. You go into a room, there’s a blue light, maybe some kind of repetitive text or image or video and someone’s got a synth and played with the filter for a bit. As someone making art and writing about art in their twenties I just feel like, “Okay, I get it. The internet can be stressful.” But I feel that slowly, this being the very beginning, we’re moving in a direction where people have a desire for humanity in art.

Perhaps we’re starting to get towards this idea that rather than telling each other stuff, we’re trying to get towards an inherent understanding of the things that we don’t say. This symbolic relationship with art, where something is busy and it doesn’t communicate so directly – which has been a consistent thread in your own work.

LG: It’s interesting when one talks about this internet idea. Before the internet, I would hang around in libraries, just browsing more than anything. Looking for information on something, be it how to replace the engine in a Citroën versus something vaguely pornographic… Just anything to distract me.

I was always drawn to the unauthored woodcut or the illuminated manuscript, the thing that is kind of used for illustrative purposes. My decisions to use these images are based on my need for particular characters. For example, I’ve always been drawn to this idea of the green man or the wild man that exists in many northern European cultures. I needed animals and I needed people working. Rather than the classic idea of the peasant and the artisan, I needed different roles – the scribe, the knight, the brewer, the farmer.

What you have to do is get rid of all the religious imagery. And going through a lot of these online libraries of scanned material, a lot of it is religious. I’m a godless heathen so I try to avoid that for the most part. I was looking for images of people that were engaged in production. I’ve used and recycled these images for various things but there’s a general trend in the work about trying to talk about questions of labour and questions of work without really resolving anything.

Also having a little bit of stupidity and a little bit of trying to extend time, I was really influenced by Eric Hobsbawm when I was younger and had more of a kind of revolutionary intent. He was a great Marxist historian who died a few years ago and wrote these long histories of capitalism starting in the sixteenth century. I’ve always been interested in combining a long modernity with a short one, that’s what this show kind of is. A long modernity goes back to the middle ages and a short modernity goes back to the start of the 20th century.

That extends what you were saying about this idea of humanity, something that we could say is already a discredited idea, but as a new way of imagining human relations. Real, concrete human relations within art would involve rethinking the trajectory of modernism, meaning rethinking a kind of art logic.

For most of the twentieth century there has been a logic in art, there has been a drive towards something. I’ve been trying to show both sides of that, the long and short modernity. I’ve been interested in the relationship between modernity and the trajectory of modernism, which are two different things. We all know it every day, which is partly what causes these anxieties and these cliché artworks. The trajectory of technology is out of sync with the thing that reflects back to it. It’s getting a grip on this out-of-sync-ness that drives the most interesting cultural work.

But art is also about being stupid, it’s about being wrong and not doing the right thing. About being unclear and not communicating.

Liam Gillick, A Depicted horse is not a Critique of a Horse, is at Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, until 19 January