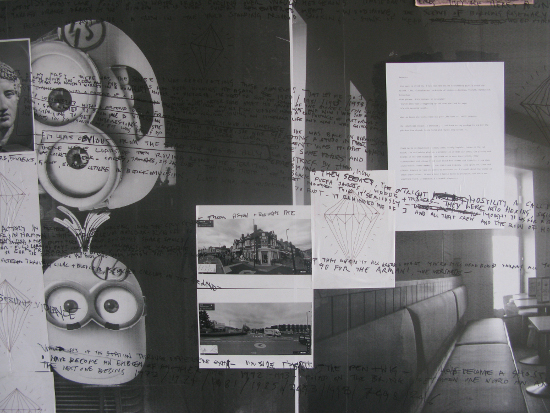

For her solo exhibition Chthonic Reverb, Laura Oldfield Ford has refocused the way in which her work is encountered by a viewer; her audio work HERMES CHTHONIUS permeates Grand Union, focusing the viewer on sonic quality of her urban drifts. The visual work in the gallery comprising of A0 photocopies of drawings and written texts placed onto a wood and sitex structure has a quieter focus, giving space for the sound to become expansive and filmic. Photocopied images of Hermes and Nemesis sit amongst those of dereliction and redevelopment, a reminder of the undercurrents that are present in the places that we pass through unknowingly.

The exhibition manifests a re-reading of Birmingham, the city she lived in during the early 1990’s, one that has now shifted its axis. To develop this work Oldfield Ford spent six weeks in residence at Grand Union in the early summer of 2015 to research Digbeth, it’s layers and history as a point of migratory arrival, its transience and outer wastelands. On her return in 2016 it is these outer areas that have drawn her focus. Chthonic Reverb utilises the galleries location by the Grand Union Canal as a fault line through intersecting areas of regeneration outlined in the Birmingham Big City Plan. Work been made for the exhibition through an intense series of dérives, Situationist inspired yet reactive to this present time. The act of walking as a methodology for reading a locality can reflect the flux present in the area in which Grand Union is sited. It reveals the layers of governance and ideology that designate, mark, and then seemingly abandon the urban landscapes we pass through.

In Birmingham, plans for HS2 have demarcated land for what has been breathlessly termed as a supercharged future. Currently this space manifests itself as a fluctuating zone in which past, present, and the promised future sit together; a place newly named as Eastside that runs parallel to Digbeth. This area of ‘transformation’ holds: a university, a city park planned to form a pathway to central shops and malls, the surviving structure of Curzon Street Station, and the Woodman – one of two surviving pubs that mark the shifting identity of the area.

One of the casualties of this current wave of regeneration has been the ongoing erasure of Sir Herbert Manzoni’s dreams for the freedom of the car in the city. Manzoni, Birmingham’s city engineer and surveyor (through WWII to early sixties counter culture) manifested the inner ring road as concrete collar that encircled the city; sweeping away the logic of the original street patterns through compulsory purchase and slum clearance (acts vividly depicted in Honor Gavin’s book Midland).

For Oldfield Ford this act of monumental erasure has been an unwitnessed event, experienced only through the realization of encounters with voided brutalist stairwells and incongruous passageways that echo the presence of the long demolished Masshouse Circus.

The site, once home to a vast concrete subterranean carpark, is now Masshouse Plaza, an empty connection to the edge of the city centre. Areas with aspirations for sitting and being seen in are echoed on the hoardings of yet to be opened offices, restaurants, and student housing. On these boards, digital renderings of busy people live on seamlessly, unhampered by the realities of rough sleepers or commuters squeezed onto buses.

Chthonic Reverb presents a social geography that maps and charts the outliers of Birmingham’s Big City Plan. Oldfield Ford’s work has moved past the obvious markers of inner city gentrification: the locations where pop-up diners jostle next to taxi hire firms, where large-scale commissioned murals for films and club nights are sprayed on the side of buildings. These are spaces that speak of creativity in one breath and gentrification in another.

Next to these urban sureties Oldfield Ford has been drawn to something other. Areas that are in-between names, waiting for a promised future and implicated by the renewal that is taking place on their doorstep. Places so unfamiliar your comprehension drops. Interdictory spaces, liminal, roughly tagged, in which you are acutely alerted to your visibility and the gaze of others. These are the places in which you perceive an expectation for payment of tithes to unseen guides, sites in which your pace quickens as you seek the first exit out. Points of reference that she cites as engendering a physical biliousness and immediate need to move on.

Within Grand Union a temporary structure focuses this exploration of boundaries and chthonic paths, timber walls alternately painted with dusty rose and black emulsion form zones to pass through. Metal Sitex sheets are spaced block passage, yet have a porousness to light. The audio work HERMES CHTHONIUS becomes your first encounter with the exhibition. Played on a loop, you might meet it at any given point. It is placed in an area with the blind drawn over the window, hemmed in and purposely blank, the gallery perfumed with rosemary oil (an aid to memory) you listen. Oldfield Ford’s voice articulates the delirious melting heat of early summer, a warmth that crystallises the city. The audio evokes the rosebay willowherb and buddleia thriving in the abandoned spaces that are traced through her walks. You listen following paths taken through spaces inhabited by echoes of their past histories. The work formed through walks in which Oldfield Ford is led by Helen, a friend whose active knowledge of the non-functioning subterranean paths of the city marks her as a guide. They pass through portals thick with exhaust fumes, through the blank facades of coffee shops in the Bullring, to the Woodman and outwards to the Aston, a place that triggers a “deep echo of recognition, a loss of bearings and gravitational shift”. The heat triggers memories. Carly Simon’s “Why” bleeding out from the doors of pubs and amusement arcades. Jason Nevins’ “I’m in Heaven” blaring out of car windows.

The audio traces territories, “marks of gratitude” formed in the placement of rocks and pebbles in the urban environment as offerings for Hermes the god of transitions and boundaries. Seeds from wildflowers transgress walls and borders, survive blight and make homes in ruins. You bear witness to doorways, borders of arterial roads, subway walls that chart threats and refusals, marking undercurrents of violence. A subterranean pavement under a dual carriageway that hosts hierarchy of immediate human needs, multiple signs advertising opportunities to earn £200 a day from home, club nights, taxi hire, phone cards, encountered with the traffic racing overhead, and sound of thick bass thudding up from a basement below the pavement. Samples of Avelino’s ‘Welcome to the Future’ woozily advise you to stay low. In this place there is a rupture, a thick sense of violence felt by Oldfield Ford at the site of the Ben Johnson pub at Aston Triangle. The building was once home to the Birmingham Press Club, a place the ‘great and good’ came to meet in seclusion away from the masses in the neighbouring city centre. She lists names of the past luminaries who dined at its functions: Bernard Ingham, Earl Spencer, Cliff Richard, Dame Barbara Cartland, Enoch Powell, Margaret Thatcher – names that trigger a visceral bodily response, and a sense of suffocating revulsion. A repetition of dates pulls into focus and is echoed on the walls of the gallery: 1972, 1974, the miners strike at Saltley Marsh Coal Depot; 1973, the start of the neoliberal project; 1984, the Battle of Orgreave; 1989, the Hillsborough disaster; 1992; 1993; 1980; 1981; 2011; 2016, “an attempt to cover traces”; 2016, the Hillsborough Inquest heard for the final time in Warrington.

The walk undertaken in HERMES CHTHONIUS travels out of the city converging on Heartlands.

A place with a carefully innocuous name given to it in the nineties by a governmental corporation with extensive powers of compulsory purchase. A taskforce licensed to transform an area of Birmingham, that in 1992 contained hundreds of hectares of land which had fallen into terminal industrial decline. For Oldfield Ford names are a source of power. Like fixed dates, they reveal memories. To obscure them averts the active use of their power. Re-branding the area as Heartlands belies the site of Saltley and the place of victory for the miners in 1972, the first general strike by coal miners since 1926. The penalisation enacted by Margaret Thatcher for this strike (and the subsequent loss of a Conservative government in 1974, the three-day week, the power cuts and the power of the unions) is one which we still pay for now. The positioning of Nemesis in the exhibition is no facile indicator of this history, she is used in her true meaning of justice and retribution. A denouement in which truths overcome lies, an indicator of the stoicism of the many lives impacted by decades of falsified evidence and the strength needed to wait for their reparation. The social geographies that are manifested in this exhibition are deep rooted, Oldfield Ford’s work underpins the value of communal space, of walking to reconnect commonly held narratives, and how these actions create a temporal free space in which you can hold your ground in the increasingly privatised land that forms our cities.

Laura Oldfield Ford’s audio work HERMES CHTHONIUS is available on the Grand Union website, to close the exhibition Laura will lead a walk to Saltley Coking Plant on the 5th of August from Grand Union at 6pm